Congratulations to all who have successfully completed one full year of patch monitoring through participation in the Patch Monitoring Project!

The Patch Monitoring Project is an India-wide initiative for citizens to systematically monitor birds in their favourite birding patches over many years.

We present results from year-one of patch monitoring from July 2021 to June 2022. In this first year, the main aim of data analysis was to explore hidden seasonal patterns of our birds. A number of exciting seasonal patterns have emerged during this one year that are new to our understanding of India’s birds! Such learning is ONLY possible through systematic local monitoring from across the country that forms the foundation of the Patch Monitoring Project. In the coming years, we will monitor not just seasonal patterns, but also the long-term health of our bird populations.

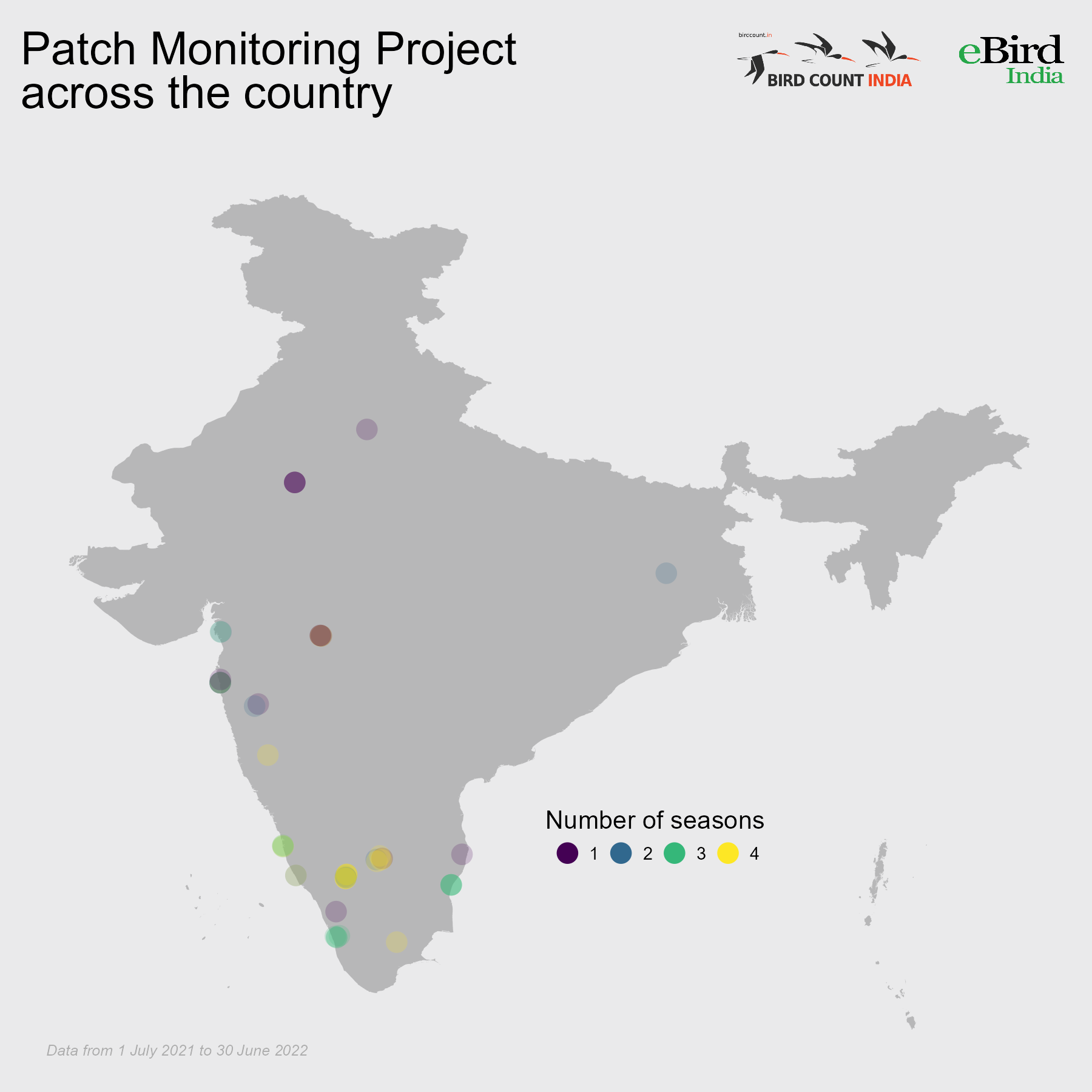

Spread of patch monitoring locations across the country at the end of year one. Are you monitoring a patch in a part of the country that is not represented here? Do start monitoring!

RESULTS

The results cover only resident bird species and are divided into 6 sections (see METHODS at the end of the article for more details). The first 5 sections focus on aggregate knowledge that have emerged from the project as a whole. Section 6 highlights observer-patch specific trends that may be of interest. The sections cover:

- Species richness

- Breeding behaviour

- Seasonality of reporting/detection

- Seasonality of aggregations

- Mysterious seasonal disappearances

- Observer-patch level insights

Click to explore ALL RESULTS in Google Drive.

Also check out the Patch Monitoring Leaderboard!

SPECIES RICHNESS

Winter is the best birding season, or so we often think. Across the Indian peninsula, resident birds are supplemented by a large number of Winter migrants. But is Winter always the best season for birding in our local patches?

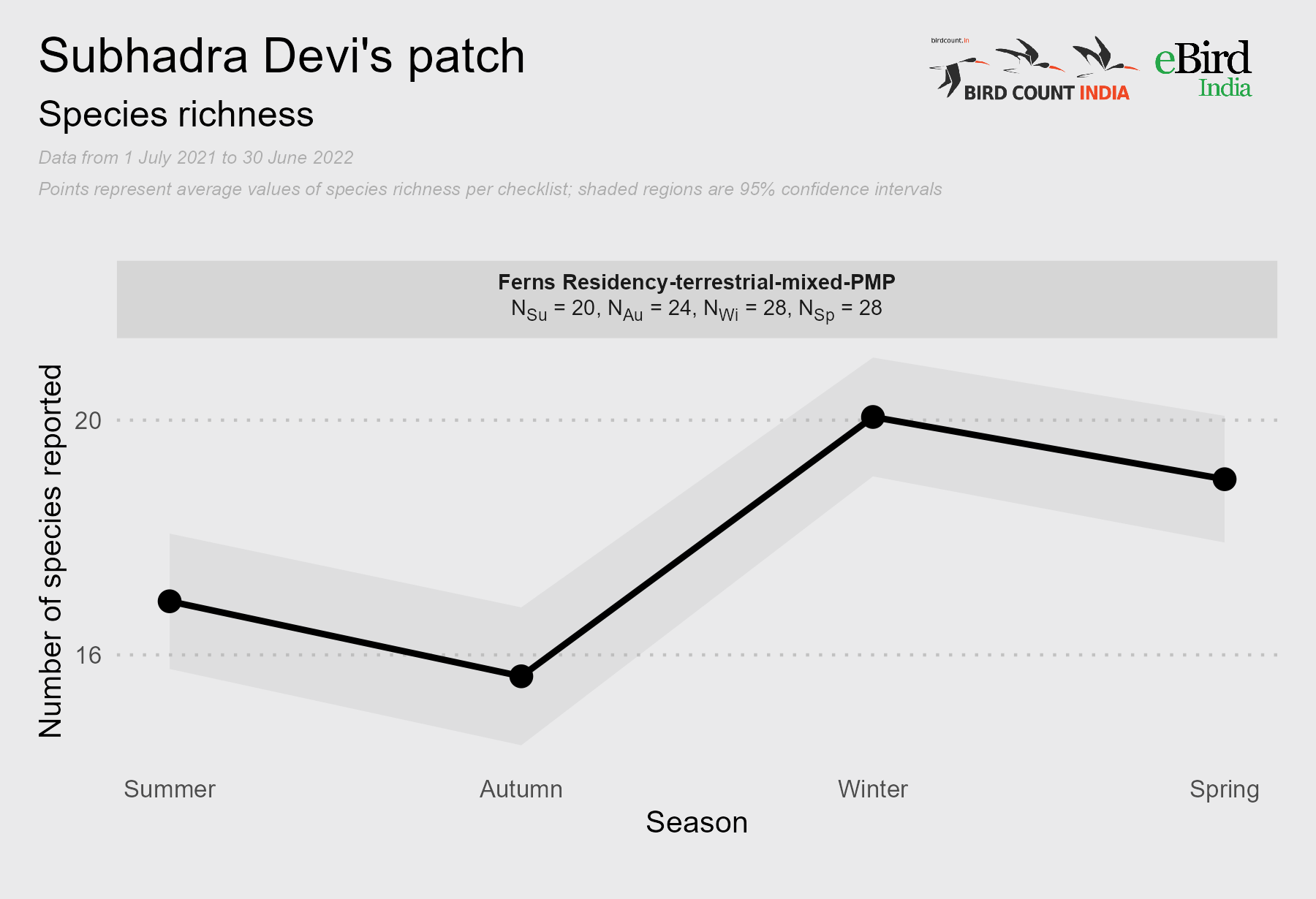

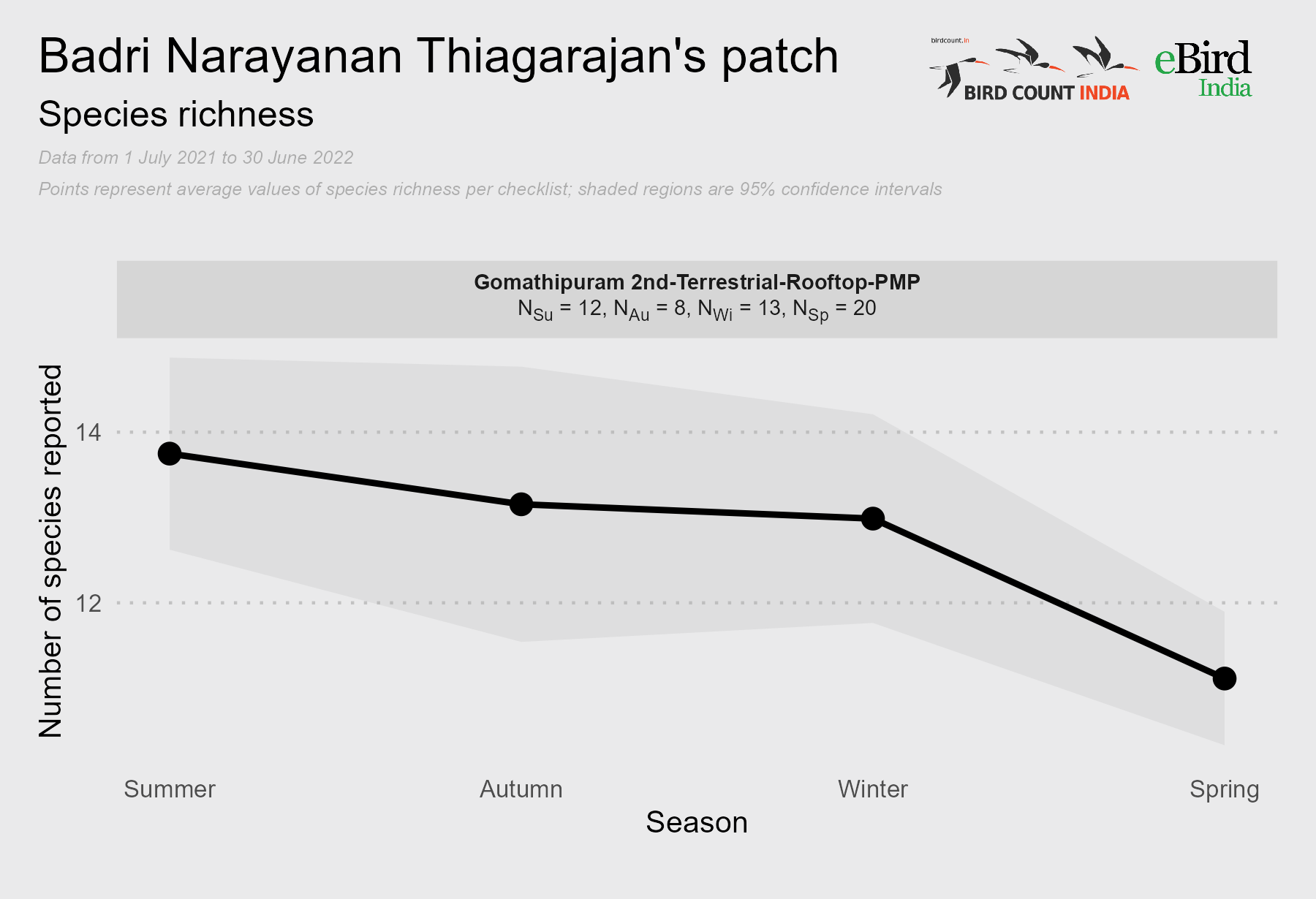

No, the data says that this is not always true! Although many patches were indeed most diverse during Winter (Subhadra Devi, Rama MV, Shyamkumar Puravankara, Sahana M, Lakshimkant Neve, Adithya Bhat, Bijoy Venugopal), other patches were most diverse during Summer and Monsoon (Rama MV, Lakshmikant Neve and Badri Narayanan Thiagarajan).

This patch is most diverse during winter (Bengaluru, KA)

And this patch in Summer (Madurai, TN)

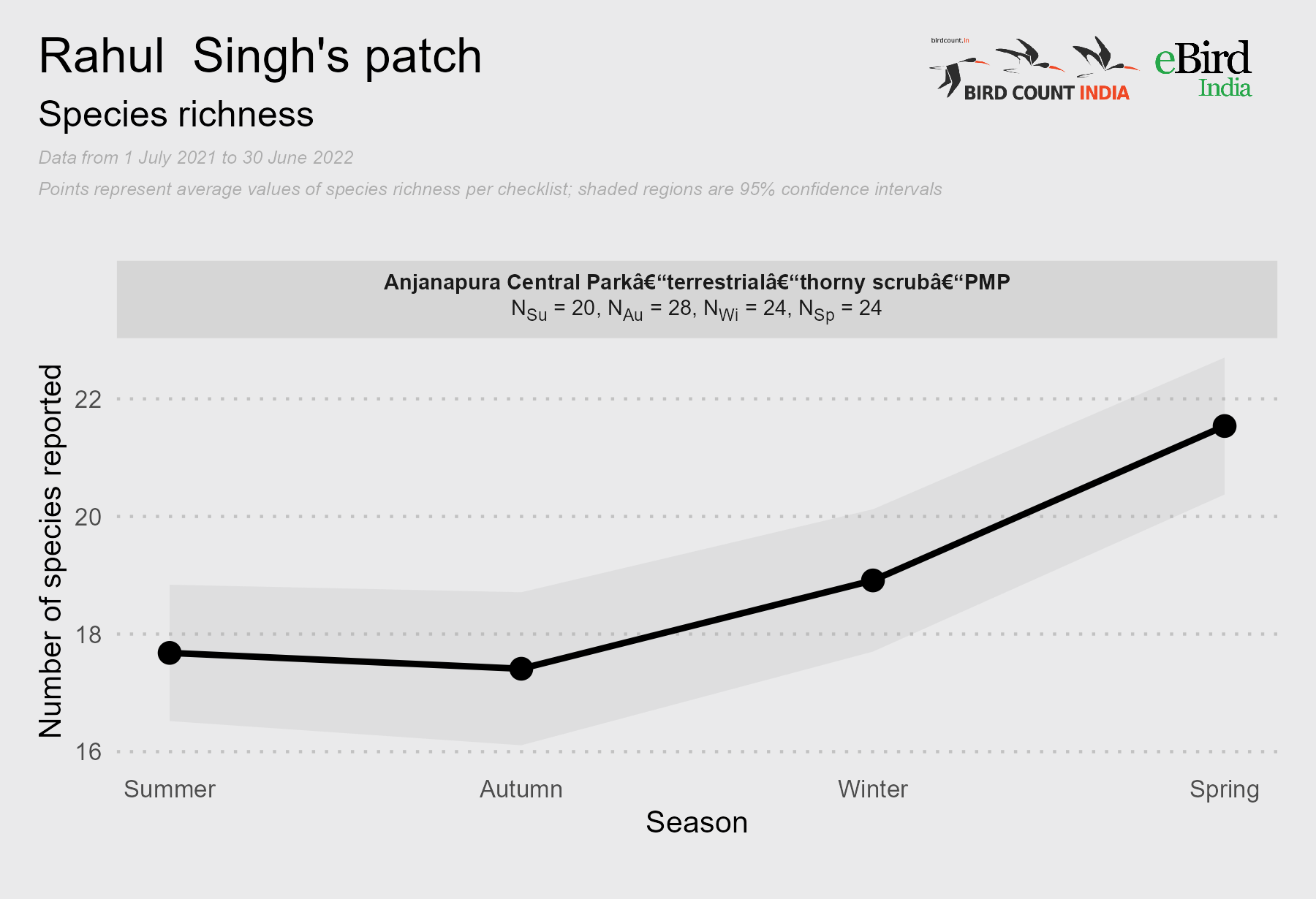

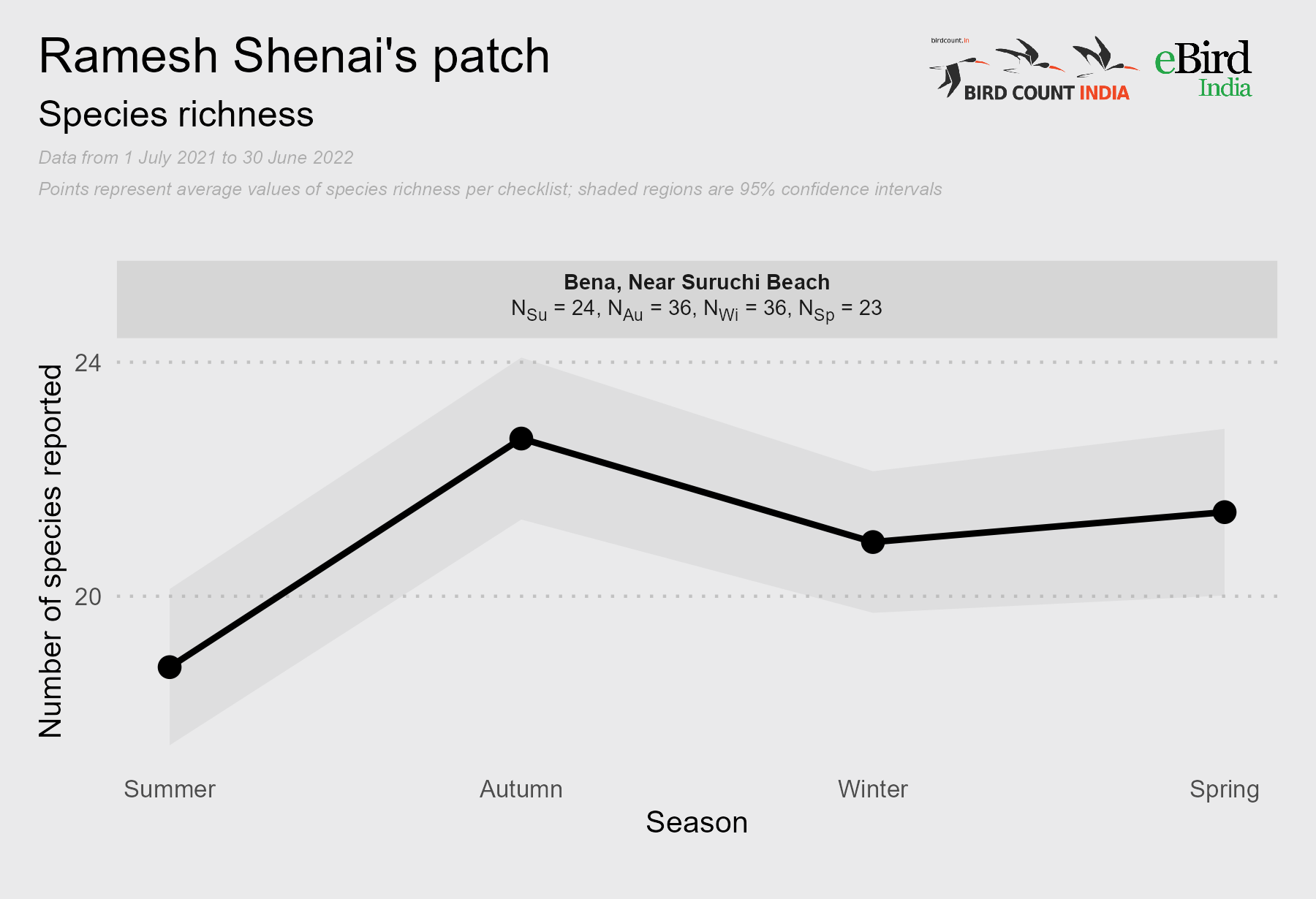

We often hear of regions like Kachchh in Gujarat and Ladakh being particularly favourable for birdwatching during Spring and Autumn migration as birds move through to their wintering grounds. Similarly, a number of focal patches appear to be excellent stopover sites for migrants, some in Spring (Rahul Singh, Subhadra Devi, Rama MV, Bijoy Venugopal) and others in Autumn (Ramesh Shenai, Sahana M, Bijoy Venugopal).

This patch is most diverse during Spring! (Bengaluru, KA)

And this one during Autumn! (Thane, MH)

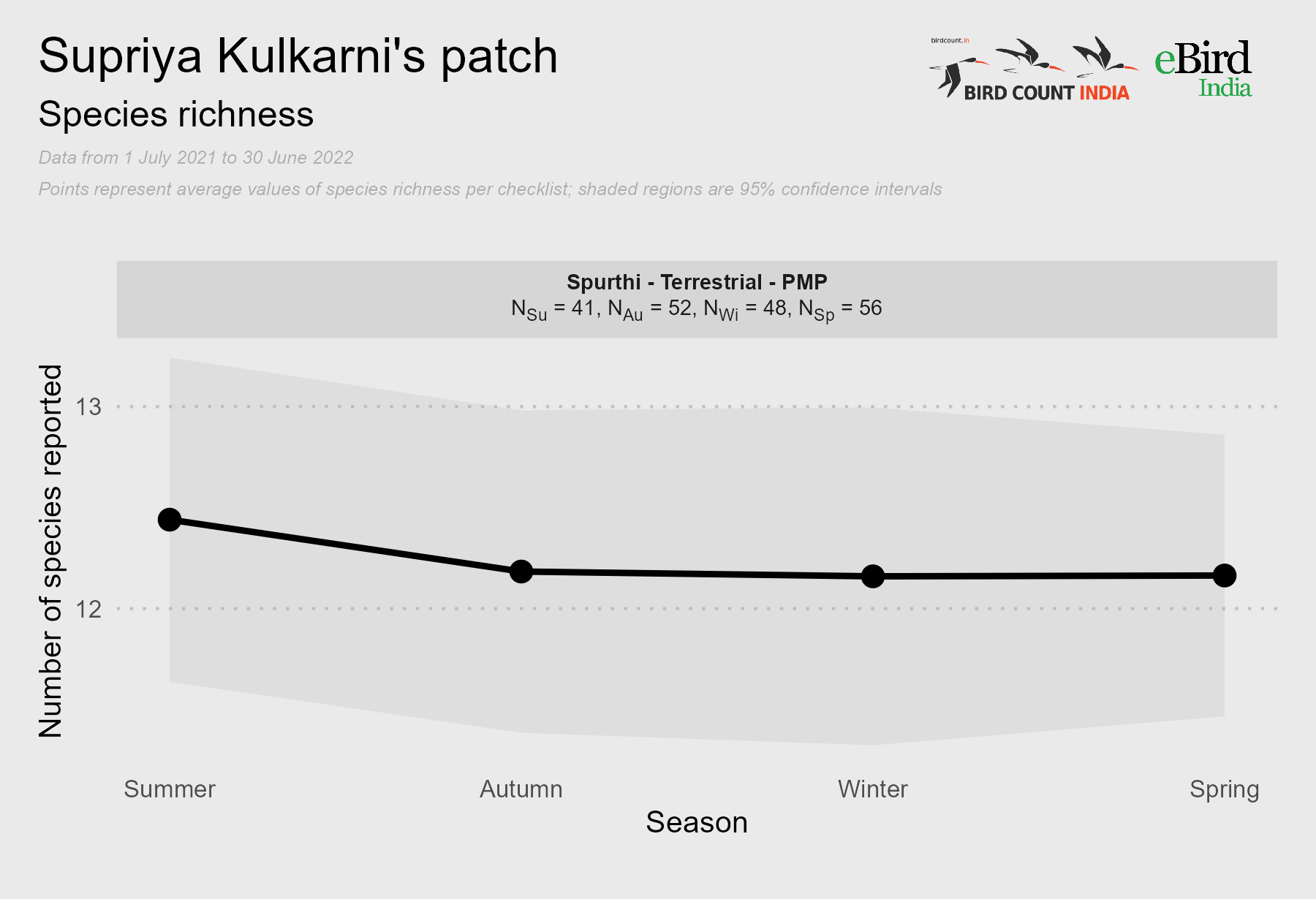

Patches monitored by Supriya Kulkarni and Pranav Datar were equally diverse year-round!

This patch is similarly diverse year-round (Bengaluru, KA)

We will know from next season how much these patterns change year by year.

BREEDING BEHAVIOUR

A number of observers monitored the breeding biology of species in their patches by documenting any behaviour associated with breeding. Documenting breeding behaviour in an eBird checklist is easy and of immense long-term conservation value. A special shout out to all those who monitored breeding behaviour!

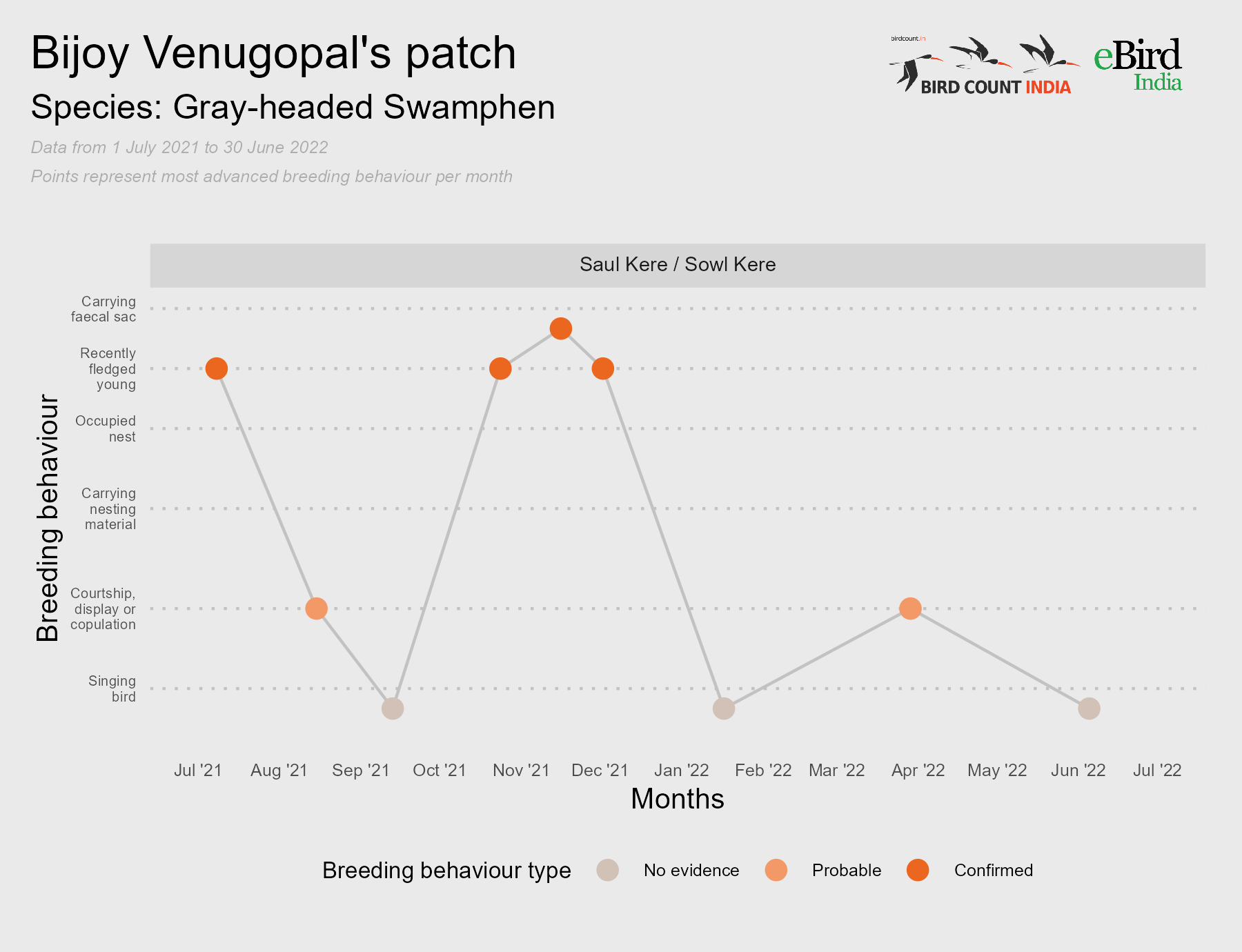

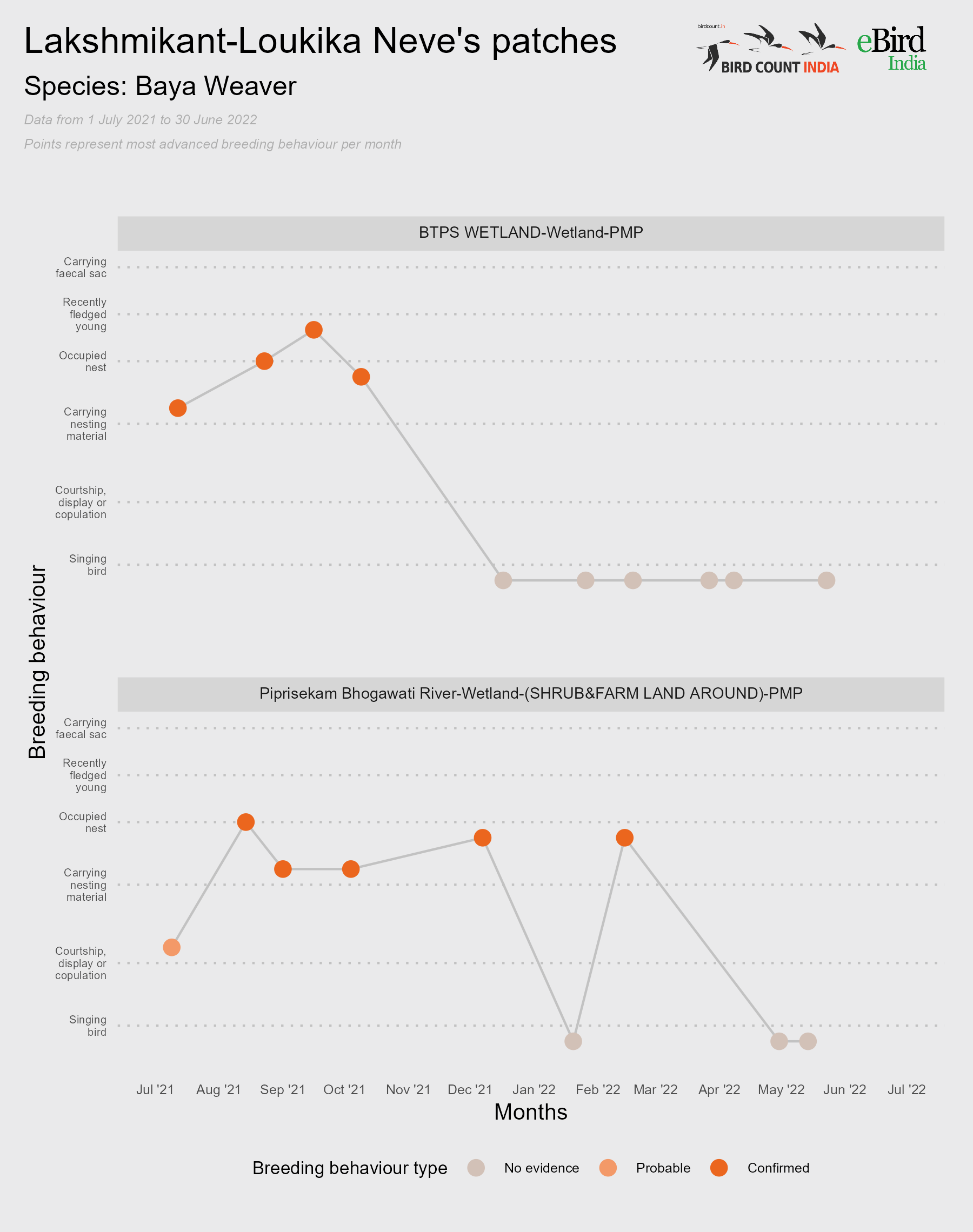

A general pattern that has emerged is something that we all suspected – Summer (includes monsoon, Jun – Aug) are the main breeding months for a number of species in the peninsula. During this season, Ashy Prinia (Vikas D Prasad), Cinereous Tit (Subhadra Devi), Baya Weaver (Rahul Singh and Lakshmikant Neve), Pheasant-tailed Jacana, Grey-headed Swamphen and Eurasian Coot (Bijoy Venugopal), and Shikra (Badri Narayanan Thiagarajan) were all documented in advanced stages of breeding. Will these patterns change in the coming years due to phenomena like climate change? Let’s see!

Albin Jacob, https://ebird.org/checklist/S32467674

Grey-headed Swamphen had recently fledged young in July, but also from October to December (Bengaluru, KA)

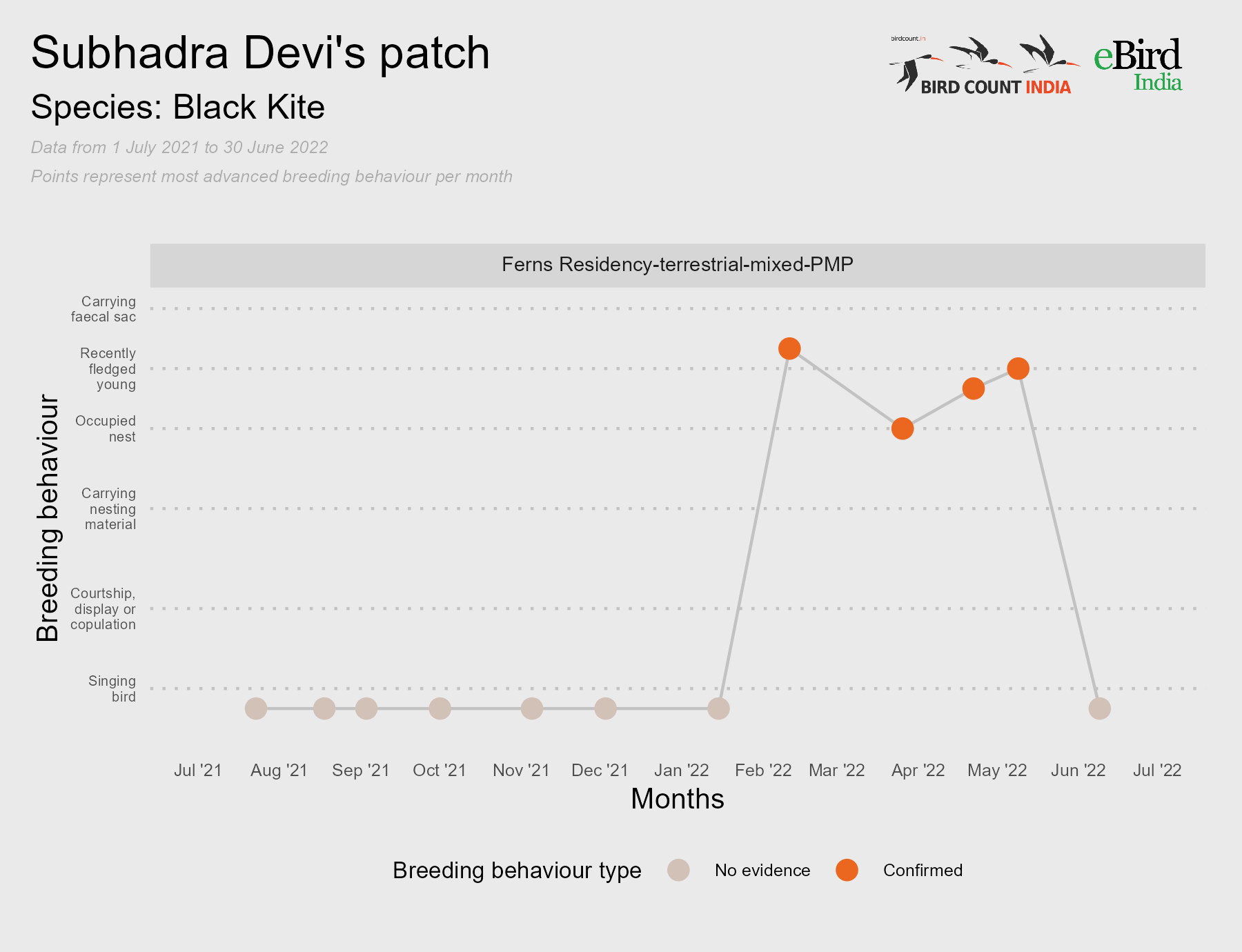

As we might expect, Baya Weaver showed signs of breeding in the monsoon and post-monsoon (Bhusawal, MH)

Black Kite was one species that did not follow this pattern, and had fledglings from February to May, as may be the case for many raptors that tend to breed during Winters. Subhadra Devi, in the same patch, also documented fledgelings of Cinereous Tit in both May and and in August, indicating that they had at least two successful broods. Bijoy Venugopal observed breeding activity of Eurasian Coot almost throughout the year at Saul Kere. Did anyone else observe multiple breeding attempts by a single species in a season?

Unlike many birds, Black Kite was observed with chicks during Winter (Bengaluru, KA)

WHEN ARE OUR BIRDS MOST FREQUENTLY REPORTED?

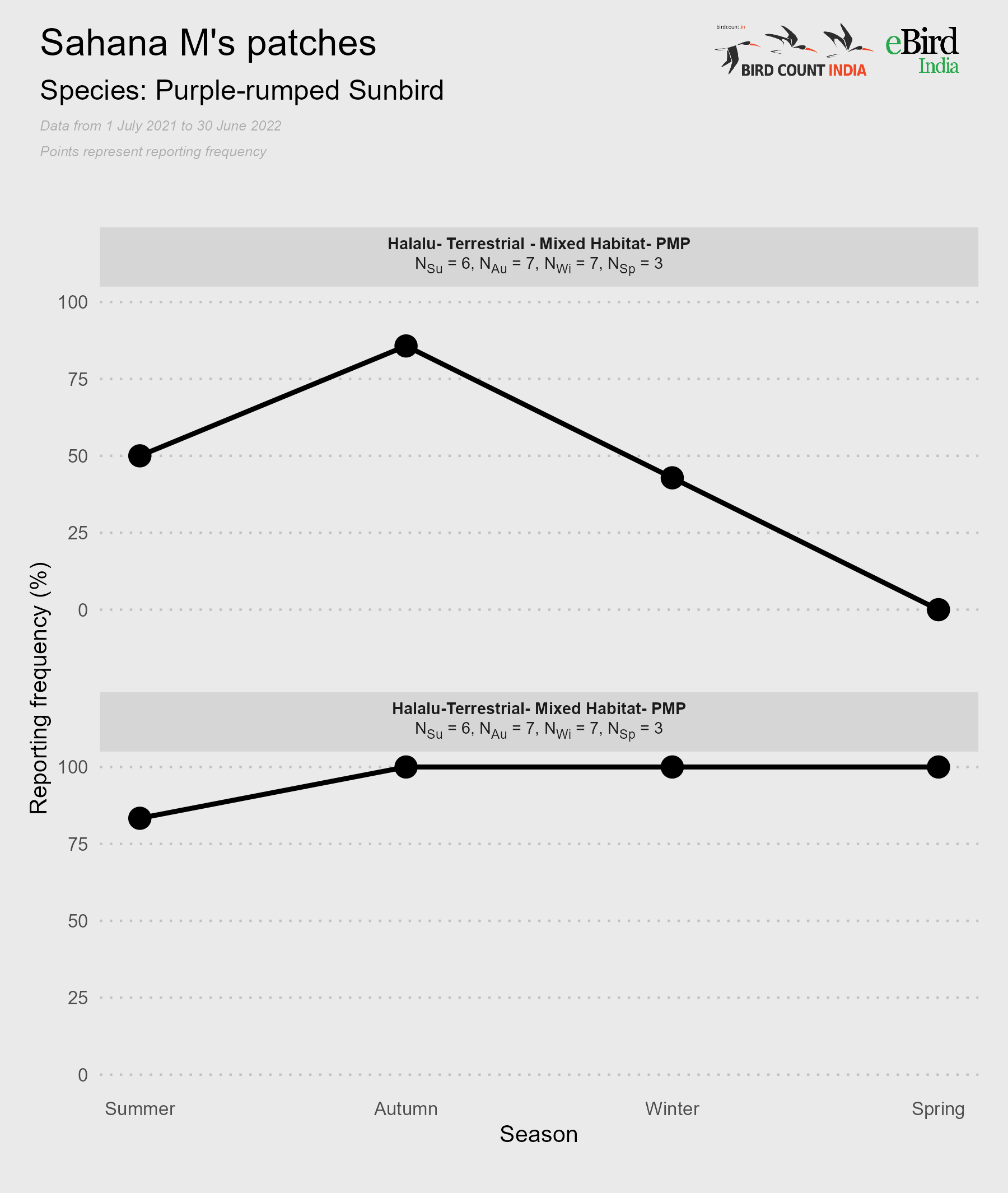

Birds are often most easy to find when they are singing and engaged in breeding activity, a period that is conventionally thought to coincide with Spring and Summer. The data shows that nearly an equal number of our resident birds are most detected/active in each of Winter (15), Spring (17) and Summer (16). Purple-rumped Sunbird appears to be an exception and was reported most frequently during Autumn (Supriya Kulkarni, Rama MV and Sahana M) or during Winter (Subhadra Devi). Could there be an ecological reason for this?

Garima Bhatia, https://ebird.org/checklist/S43446884

Purple-rumped Sunbird is reported most frequently during Autumn in one patch, but not in the other (Mysuru, KA)

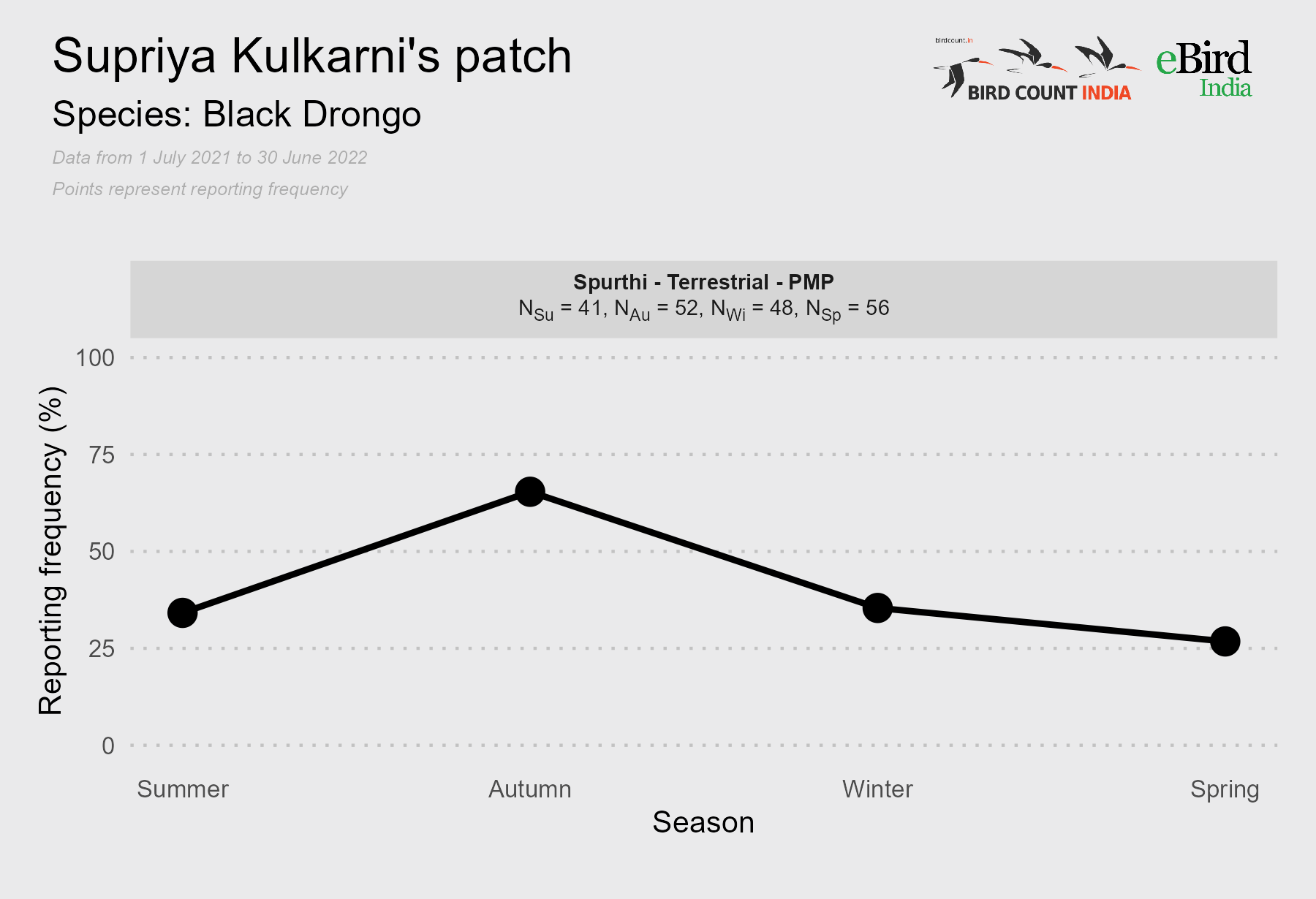

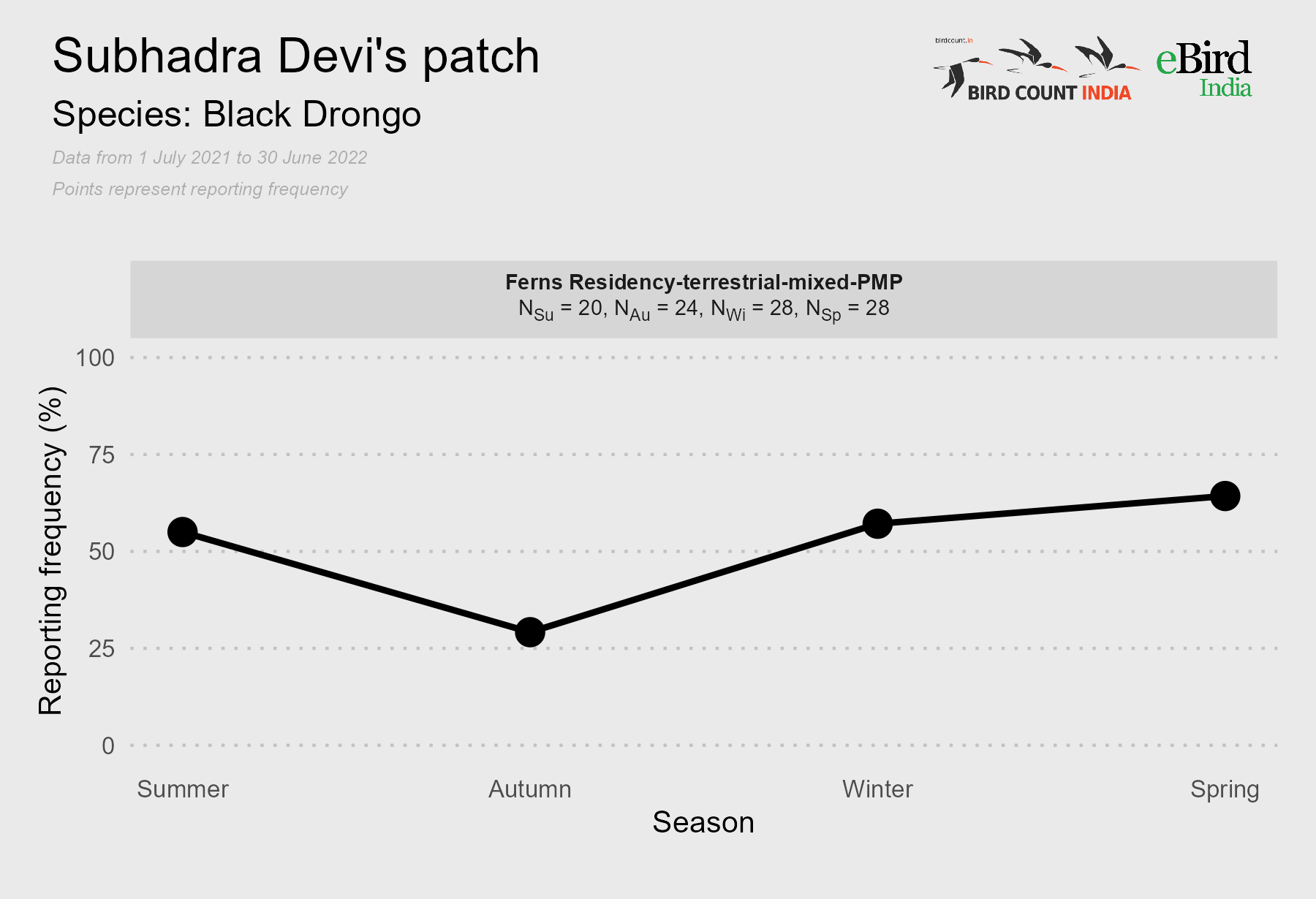

Other interesting general patterns include: 1) Black Drongo is most common during Autumn in one part of Bangalore (Supriya Kulkarni) but least common during that season in another part of Bangalore (Subhadra Devi)! Does this imply local migration? 2) ‘Singing’ birds such as Chats, Warblers, Prinias, Monarchs are most active during Spring and Summer.

Black Drongo becomes more common during Autumn (Bengaluru, KA)

The pattern is inverted here in another patch from Bengaluru, KA!

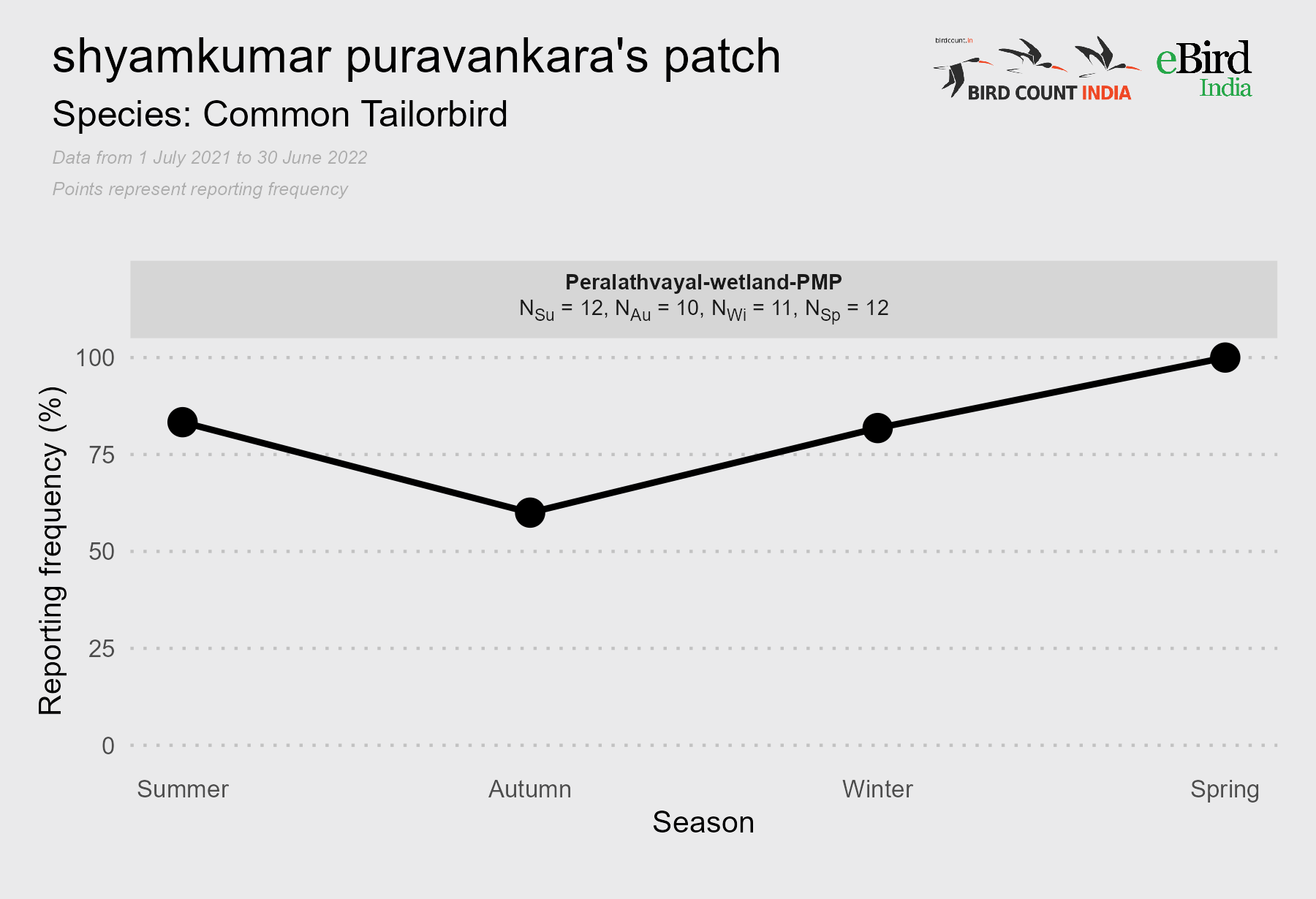

Common Tailorbird is one of many songbirds that are reported most often during Spring (Kasargod, KL)

SEASONAL AGGREGATIONS

How much (and why) do our resident bird numbers change within a patch across seasons? Can the seasonal changes in numbers inform us about migrations and the possibility of local populations being supplemented by migratory ones?

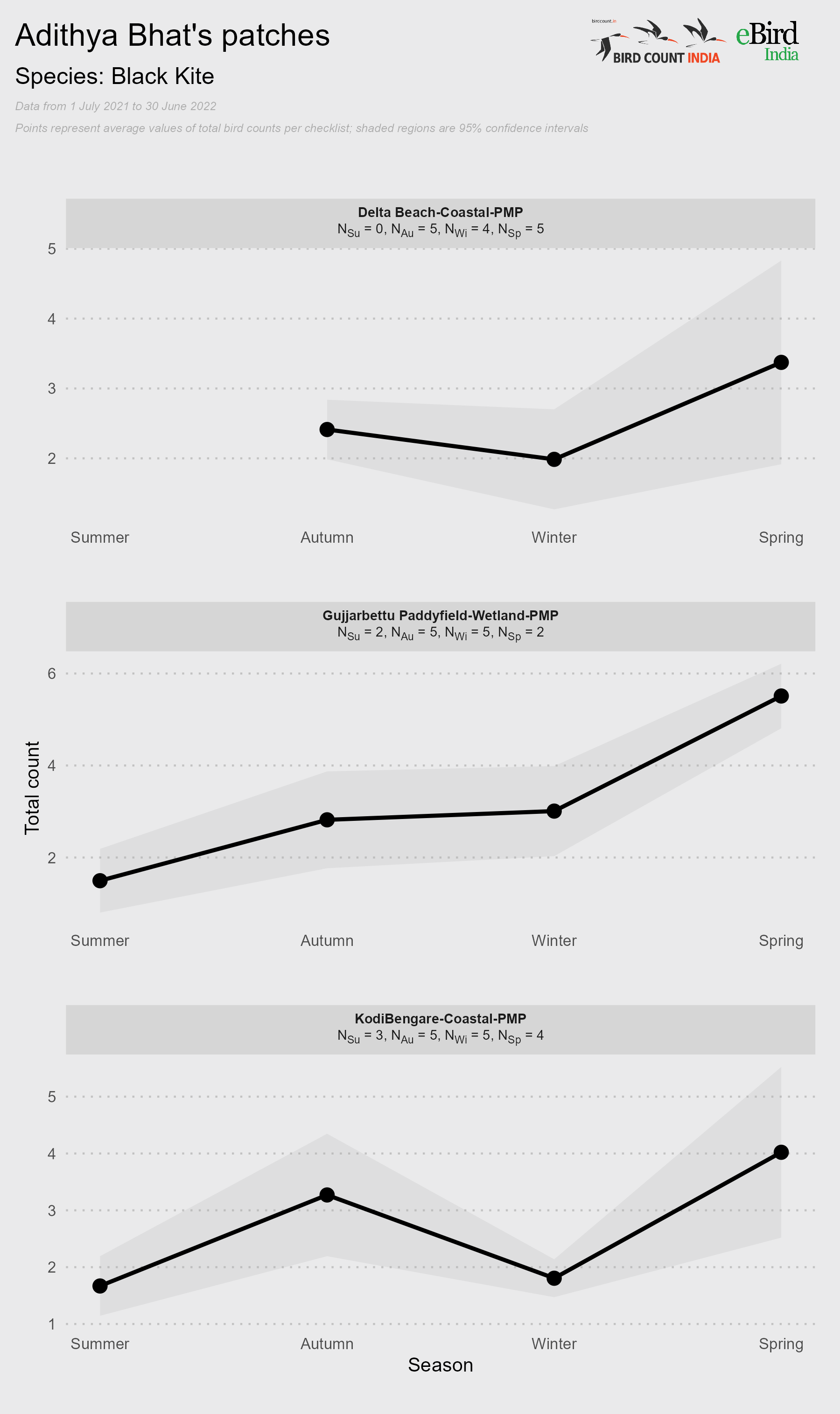

Black Kite numbers increase from an average of 2 birds to 6 birds per checklist during Spring in the Karnataka coast (Adithya Bhat), possibly indicating Spring passage movement of Black Kites through the area. In central India, the highest counts of Cattle Egret were observed during Summer (Lakshmikant Neve), perhaps indicating that populations are supplemented by returning birds that had migrated south duirng Winter?

Subhadra Devi, https://ebird.org/india/checklist/S62283262

Where do Black Kites go in the Summer? (Udupi, KA)

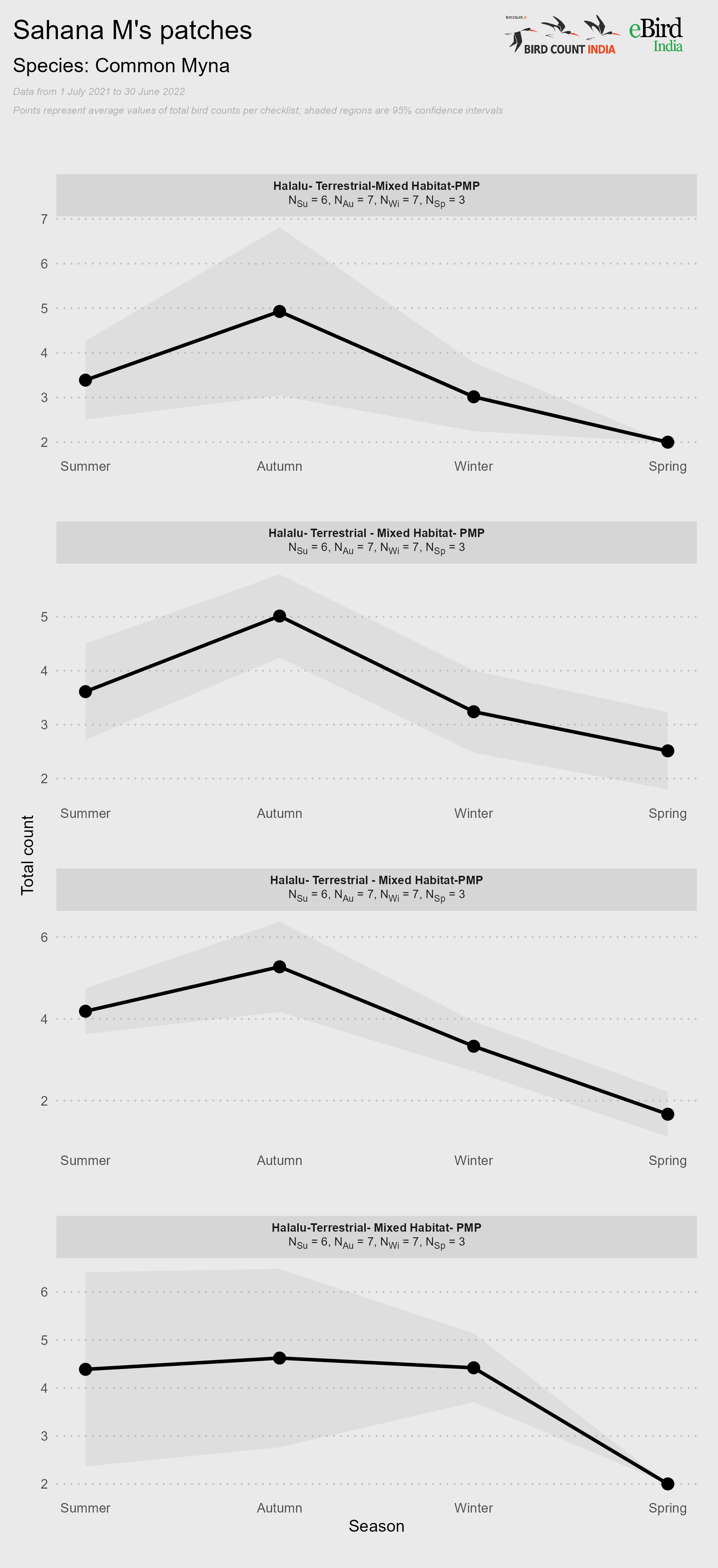

Common Myna aggregates in Autumn and Winter (to search for food resources?), a phenomenon documented in 4 patches (Sahana M, Ramesh Shenai, Supriya Kulkarni, Lakshmikant Neve)!

Bhaarat Vyas, https://ebird.org/checklist/S79913610

Why are larger numbers of Common Myna reported in Autumn? (Mysuru, KA)

MYSTERIOUS SEASONAL DISAPPEARANCES

Seasonal disappearances of ‘resident’ birds are truly intriguing. Bay-backed Shrike, for example, is considered ‘resident’ but is an Autumn passage migrant in many parts of the country. Where are these birds coming from and where are they going? Many such mysteries have presented themselves from patch monitoring.

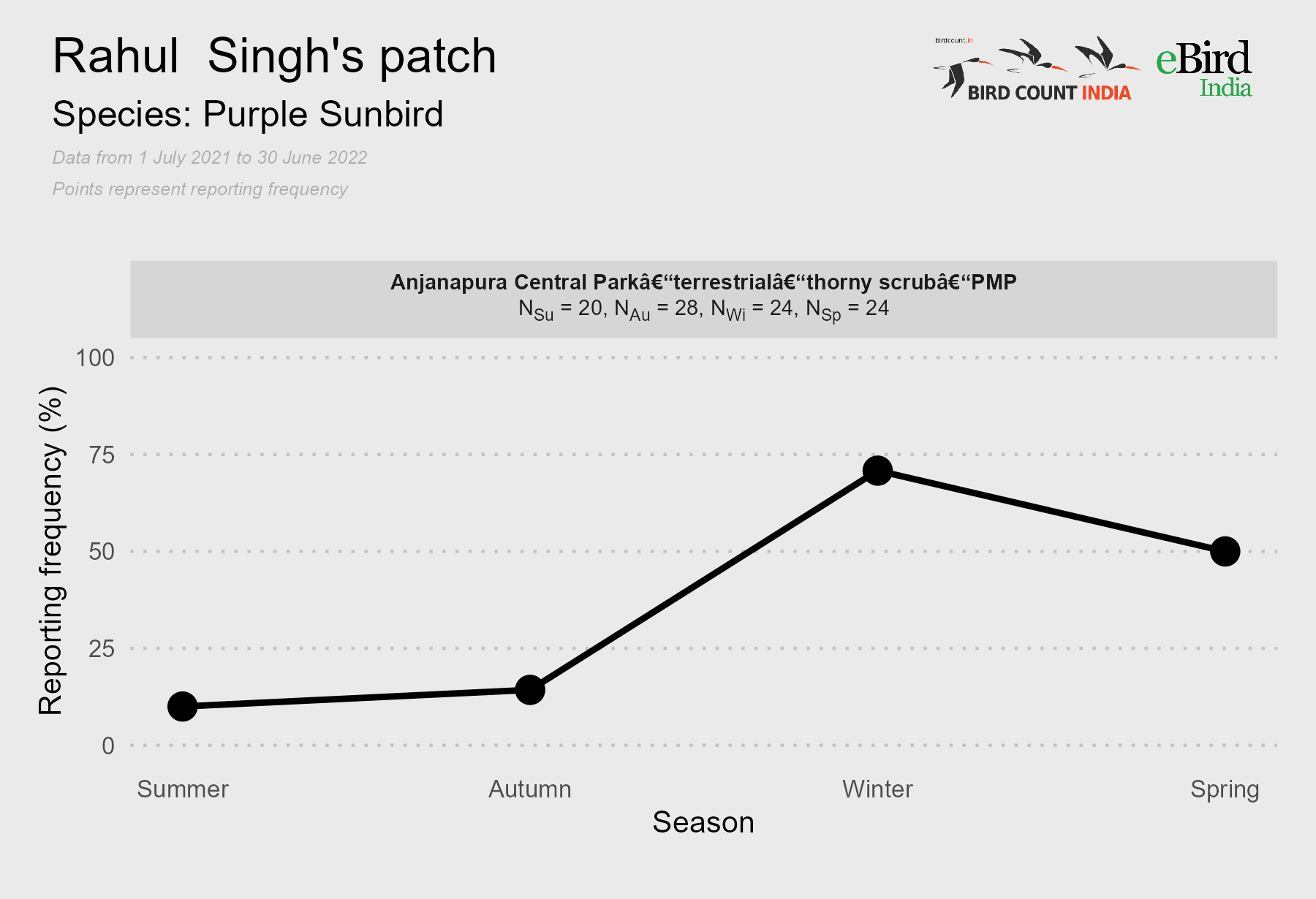

Purple Sunbird disappears during Summer in some parts of Bangalore (Rahul Singh, Supriya Kulkarni). Where do they go?

Purple Sunbird nearly disappears during Summer! (Bengaluru, KA)

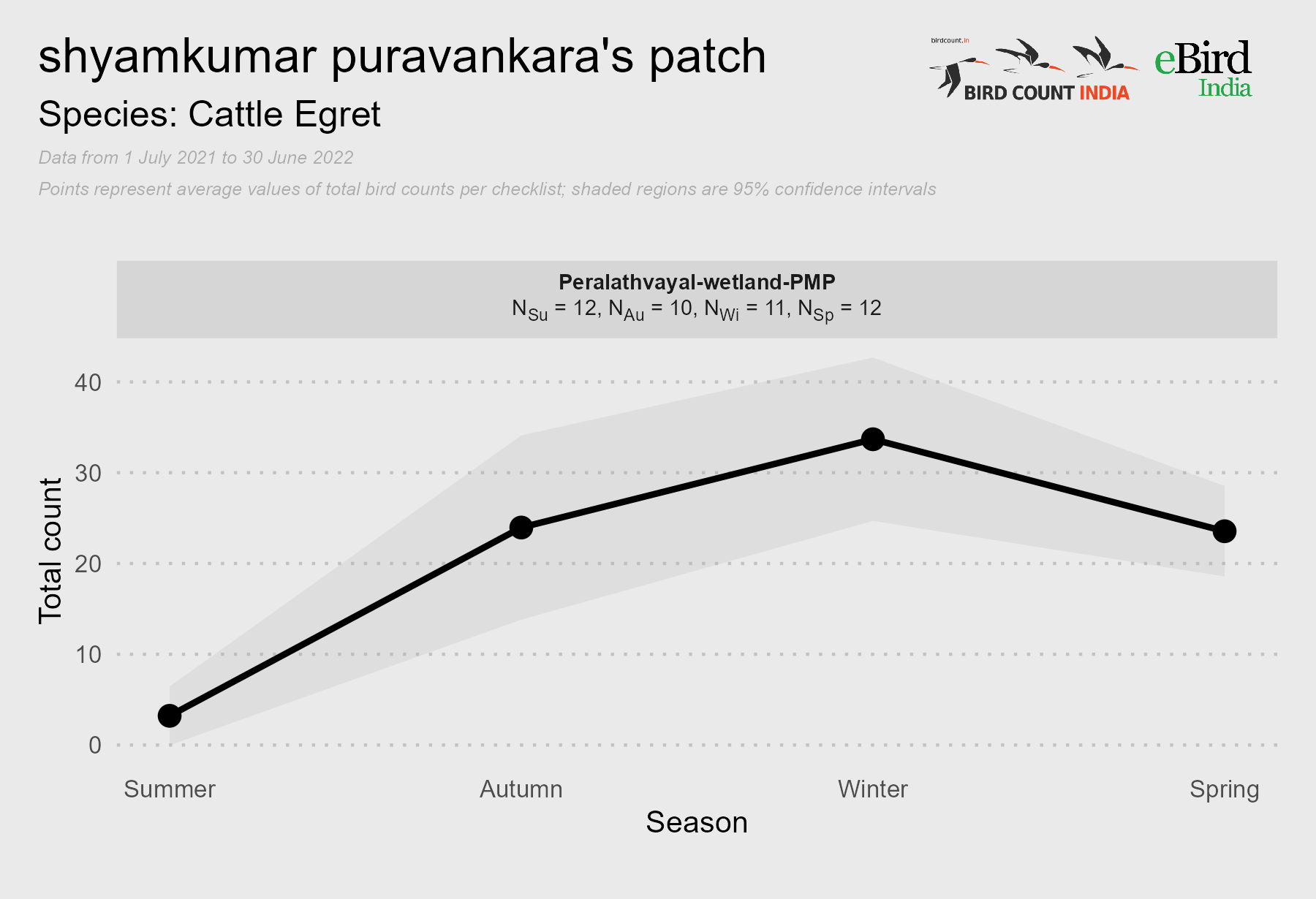

Cattle Egret disappears during Summer in some parts of southern India (Shyamkumar Puravankara, Rama MV). Do they go north, to Lakshmikant Neve’s patch for example?

Do Cattle Egrets migrate to southern India during Winter? (Kasargod, KL)

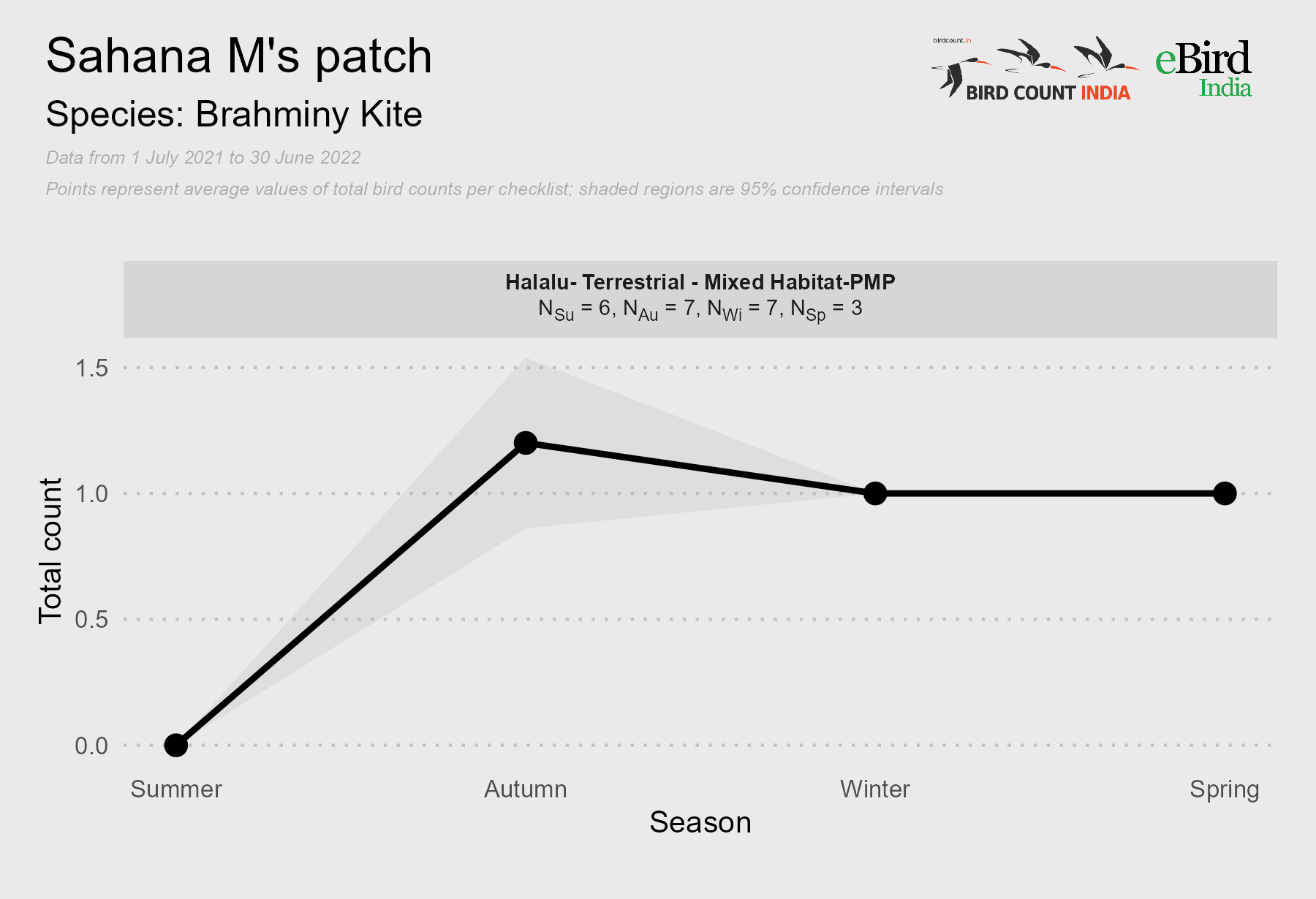

Brahminy Kite disappears during Summer in a patch in Mysore (Sahana M). Where do they go?

Where did this one Brahminy Kite go during Summer? Will to disappear again? (Mysuru, KA)

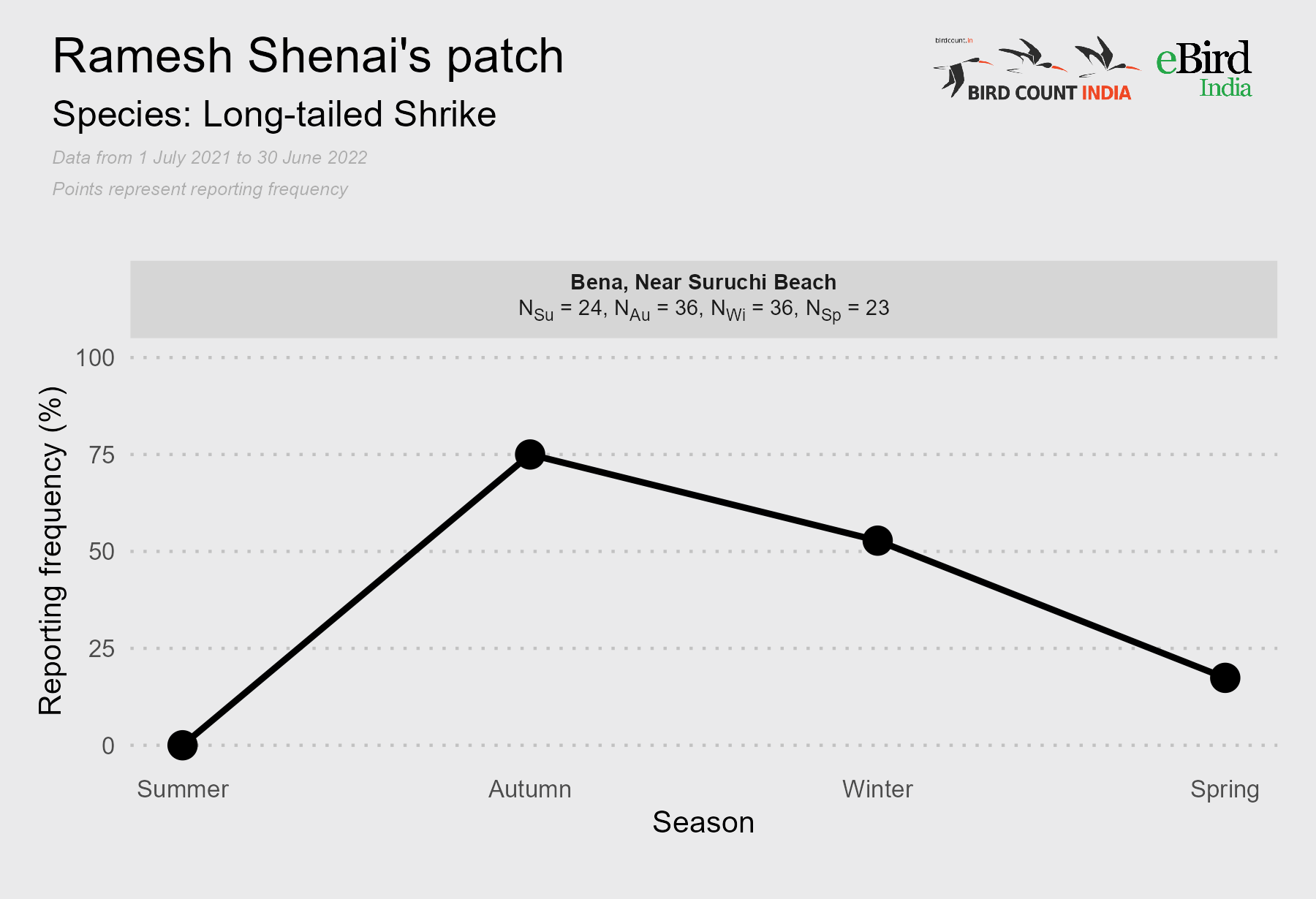

Long-tailed Shrike is a Winter visitor to a patch in coastal Maharashtra (Ramesh Shenai). Is it a local or long-distance migrant?

Ramesh Desai, https://ebird.org/checklist/S61965951

Where do these Long-tailed Shrikes go during Summer? (Thane, MH)

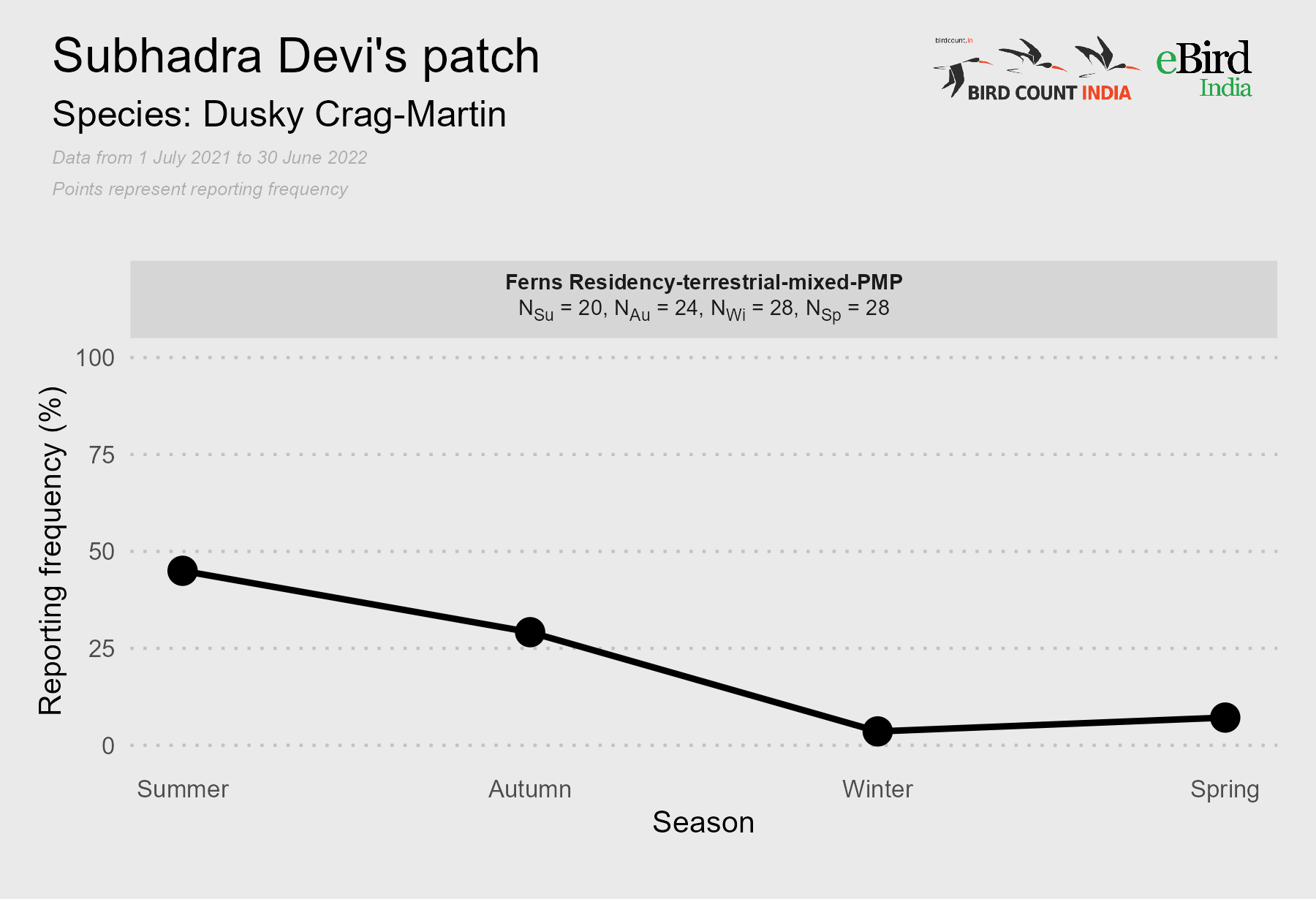

Dusky Crag-Martin disappears during Winter in a patch in Bangalore (Subhadra Devi). Does it go to nest in nearby high rises?

Will Dusky Crag-Martin once again be encountered frequently come Summer and Autumn? (Bengaluru, KA)

Some other species are completely unreported during either Summer (Striated Grassbird – Lakshmikant Neve) or Winter (Jungle Prinia – Subhadra Devi, Indian Peafowl – Pranav Datar, Zitting Cisticola – Subhadra Devi) but this may be a consequence of little to no activity during that season rather than movement. What do you think?

OBSERVER-PATCH SPECIFIC HIGHLIGHTS

Adithya Bhat

Frequency:

- Common Tailorbird reporting declines sharply (50%) from Autumn to Winter (lower detectability?), but only in the coastal patch and not in the paddyfield.

Counts:

- Brahminy Kite numbers increase in Spring, both in wetlands and on the coast. Does this imply local migration?

Richness:

Badri Narayanan Thiagarajan

Frequency:

- In contrast with Adithya Bhat’s patches, here Common Tailorbird has almost 50% lower frequency in Autumn than in Summer and Winter.

- Rose-ringed Parakeet reporting is lowest in Winter (almost 50%), but no corresponding changes in counts were observed.

- Shikra reporting is much lower in Summer than other seasons.

Bijoy Venugopal

Frequency:

- Alexandrine Parakeet reporting is lowest in Spring (nesting?) and highest in Autumn (fledgelings + greater mobility?).

- Cattle Egret reporting is much lower in Summer than in all other seasons when it is very common.

Counts:

- Black Kite shows no change in Autumn/Winter but instead shows a strong increase in Spring. The famous Thailand Black Kite moved through Bangalore in January/February. Could such migration explain the higher Spring counts?

Breeding:

- Eurasian Coot breeds throughout the year! Birds of the World does not include information on the breeding seasonality in southern India.

Lakshmikant/Loukika Neve

Frequency:

- Indian Spot-billed Duck, Black-headed Ibis, Pied Kingfisher and River Tern are most frequently reported during Winter. Do they locally move to these patches during Winter?

- Striated Grassbird disappears in Summer. Do they become difficult to detect?

Pranav Datar

Frequency:

- Brahminy Kite is reported more frequently during Spring, and in higher numbers, similar to Adithya Bhat’s patch.

- Common Myna shows a decline in reporting during Winter but this does not correspond with any change in average counts.

- Indian Peafowl is completely absent in Winter and Spring!

Rahul Singh

Frequency:

- Ashy Prinia is most often reported during Summer and least often during Winter.

- White-browed Bulbul shows the opposite pattern of Ashy Prinia, and is reported most often during Winter!

Counts:

- Red-vented Bulbul is observed at higher numbers during Winter.

Rama MV

Frequency:

- Common Myna declines in frequency (but not in numbers) in just one patch during Winter.

- Green Bee-eater declines during Winter. Does this indicate local movement?

- Pied Bushchat is most frequently reported during Spring when it potentially begins singing.

Ramesh Shenai

Frequency:

- Asian Koel is not much more frequent during Spring and Summer than in other seasons (as in most other patches around the country). Is Koel less seasonal in its vocalizations here?

- Black Kite reporting increases slightly during Autumn but does not correspond with a change in numbers.

- Green Bee-eater declines during Winter (as in Rama MV’s patch) and sharply increases during Spring.

Sahana M

Frequency:

- Ashy Prinia reporting is consistent year-round (unlike in other patches).

- Grey Francolin is reported most frequently during Winter (most vocal?), a pattern that is consistent across patches.

- Jungle Prinia is similarly reported year-round in one patch, but is completely absent during Winter and Spring in another!

Shyamkumar Puravankara

Frequency:

- Black-headed Ibis shows similar overall pattern as in Lakshmikant Neve’s patch, but peak reporting shifts from Spring to Summer.

- White-rumped Munia is least reported during Autumn.

Counts:

- Black Kite numbers increase during Winter.

Subhadra Devi

Frequency:

- Black Kite reporting is consistent year-round, unlike in some other patches.

- Shikra is most frequently reported during Winter.

- White-cheeked Barbet is especially vocal (most reported) during Spring.

Supriya Kulkarni

Frequency:

- Brahminy Kite is absent during Summer! Where do they go?

- Pale-billed Flowerpecker is most vocal (reported) during Summer.

Counts:

- Rose-ringed Parakeet counts per list increased from 4 in Summer to 8 in winter!

METHODS

Only eligible patch monitoring lists and species/subspecies observations were considered in this analysis. To explore seasonality, we considered the four seasons of Summer (June to August), Autumn (September to November), Winter (December to February) and Spring (March to May). In order to prevent duplication, observers who have patch monitoring lists shared with them, but have not uploaded at least one patch monitoring list of their own, are not considered here. A suite of other filters were applied in order to make the analyses meaningful and informative. Only patches and species that had information in all three months of a season in at least two seasons were considered in the analyses.

With seasonality as the focus, metrics were calculated at two levels – 1) At the level of a patch (species richness) 2) At the level of a bird species (frequency of breeding behaviours, frequency of reporting, and counts). Reporting frequency is an index of abundance of a species, and is calculated as the percentage of total checklists in which the species is reported. Breeding behaviours were inferred for every season using the “highest” (most advanced; see here) eBird breeding code while excluding “Flyover”, “In Appropriate Habitat” and “Pair in Suitable Habitat”.

Reporting frequencies are not presented for species that were reported with more than 90% frequency in each season. We removed such very common species from any species level analysis, and instead selected the next 20 common species for each observer-patch combination, in order to allow identification of clear seasonal patterns. Counts are only presented for the following species when eligible – Common Myna, Red-vented Bulbul, Rose-ringed Parakeet, Black Kite, Brahminy Kite, Cattle Egret, Indian White-eye, House Crow and Green Bee-Eater. Breeding behaviours are only presented for those species that had at least three unique breeding codes reported in at least two seasons.

Do note that some patches are less represented in the results due to limited sample size in one season or more. Please be assured that your patch will certainly feature more prominently when all seasons are adequately represented.

Banner Image: By Dhananjai Mohan, of one of his birding patches.

❤️ happy to see the results

I want serious analysis of my whole patch ….7+ years of data available. Can Anybody from Birdcount India help me to help me for technical analysis. My daughter can co-ordinate for this. Please Reply to 8149659353 / 7588740661.