By Ramit Singal

For part 2 of the identifying pipit series, click here

It’s that time of the year when the first few winter migrants begin to trickle in. But for those who are terrified of identifying pipits, there is still some time to go before the confusing species arrive! Only one pipit species is resident across most parts of the country and that is the Paddyfield Pipit, which also makes this an excellent time of the year to familiarise oneself with the most common pipit of the region.

A young Paddyfield Pipit quenching its thirst. A pale brown bird from N India. Photo: Kavi Nanda

—

Note: Depending on where you are, be wary of other pipit species that are found in the summer. These are:

Long-billed Pipit – The nominate race breeds in rocky outcrops and habitats of peninsular India while the travancoriensis race breeds in the higher altitudes of the Western Ghats in Kerala. The race jerdoni breeds in the higher Himalayas.

Nilgiri Pipit – The pipit endemic to the Western Ghats breeds in the shola grasslands of Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

Upland Pipit – This bird breeds in the western Himalayas, across a fairly large altitudinal range and in open grassland and scrub habitat.

Rosy Pipit – A distinctive pipit that breeds in the high Himalayas, above the treeline.

Olive-backed Pipit – A pipit that is found commonly across the Himalayas and across a large altitudinal range in orchards, open forests, etc.

Tree Pipit – A pipit with a breeding population in the high Himalayas.

—

For almost every birder, pipits tend to pose a perplexing problem. In the winters especially, the ubiquitous Paddyfield Pipit (which can be seen in dry fields, wet fields, marshes, farmland, shola grasslands, parks and gardens, etc) exists alongside the wintering Tawny, Blyth’s and Richard’s Pipits – all of which can look like each other!

The Paddyfield Pipit happens to be a bird of varied plumages and markings, and also carries a fairly impressive repertoire of sounds. This is why it is one of those birds we often mistake for something more “unlikely and exciting”, such as the pipits mentioned above.

However, June to August presents a great opportunity for all birders to go out and acquaint themselves with this charming species to get a hold of some of the features that can help tell it apart from its congeners when the winter migrants arrive again.

1. Shape and structure

The Paddyfield Pipit is a very proportionately built (i.e. nothing about its overall shape seems odd, or too long or too short), compact species. It usually has a small body with a larger-than-typical head and bill, and a short tail. Getting used to the overall structure is very useful.

Paddyfield Pipit: From the SW coast of India. Note the small bodied, big-headed and short-tailed structure along with the bill shape. Photo: Prashantha Krishna MC

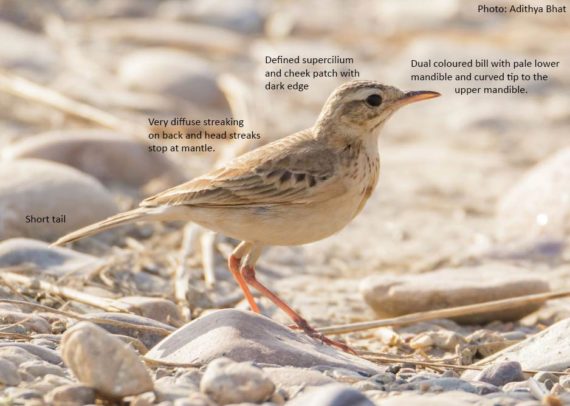

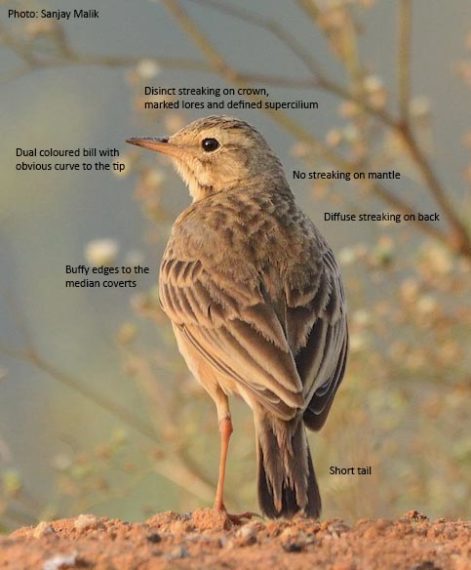

The bill is often a very good give-away. It is almost always very obviously dual-coloured, with usually a paler colour on the lower mandible and occasionally, a pale base to the upper mandible (around the nostrils). The tip of the upper mandible is curved slightly. Depending on the age of the bird, the bill can appear heavy or small and thus, it’s useful to note how much variation there is in the size of the bill itself.

Paddyfield Pipit: A bird from S India showing the dual-coloured bill, marked lores, short tail, compact structure, diffuse streaking on back. Photo: Albin Jacob

Tips: Familiarise yourself with the overall shape of the bird, its movements and posture when it is foraging. Using shape and behaviour (the “jizz” of the bird), an experienced observer can often tell it apart from other pipits. Get used to looking at the bill well and judging the shape in the field. A good look at the bill will also help set it apart from most similar pipits. Looking at the bill also gives the observer a good view and allows focus on the face – a useful area for identification (described below).

2. Plumage

The Paddyfield’s Pipit plumage can be very varied – both in colour and in markings.

The birds found in the arid and drier north-western parts of the country tend to be extremely pale. In the Western Ghats, the birds are often quite dark and appear heavily streaked. The subspecies that ranges across most of India, however, is the shade of brown you would expect on the other similar pipits.

Paddyfield Pipit: A pale brown bird from N India showing the short tail, dual coloured bill, slightly large head, marked lores, defined cheek patch, very little streaking. Photo: Adithya Bhat

2.a. Face

So what do we look for? First of all – try and notice features on the face. Most birds will show at least a hint of a loral stripe – that is, a streak between the eye and the base of the bill. This loral stripe gives the impression that the supercilium starts from in front of the eye, goes over the eye and then behind it. The caveat here is that the lores may look marked or unmarked because of the angle. The best way to judge this feature is by looking at the bird’s side profile.

Paddyfield Pipit: A not-so-dark bird from Kerala. Showing the faint streaking on the back and break in streaks on mantle, marked face (lores, cheek), compact structure. Photo: Raphy Kallettumkara

When you look at the face and the distinctive supercilium, you’ll note that this is also because the cheeks of the Paddyfield Pipit are relatively well defined, dark and often have a black border running along the top. This allows for the supercilium to stand out the way it does. Note however that this is a very variable, often unreliable feature as can be seen in the many images in this article.

2.b. Upperparts

A lot of books mention the need to observe streaking on the upperparts and heads of pipits. The streaking on a Paddyfield Pipit can be of a variable darkness and density. However, if you know what you’re looking for – you may find a few patterns within that variability.

Paddyfield Pipit: An individual from Bengaluru. Note the streaks breaking on the mantle, lack of contrast between the streaks and the brown on the back. Photo: Sanjay Malik

On most Paddyfield Pipits, there is some (weak or strong) streaking on the head and upperparts. And if you observe multiple individuals, you’ll notice that the head streaking is usually separate from the streaking on the back. This is because in almost all cases, there is little to *no* streaking on the mantle. It is worth looking at the same individual over and over again from different angles to learn to observe this with ease. This is a useful feature to be able to ascertain in the field as both Blyth’s and Richard’s Pipits usually show continuous streaking from the head down to the back across the mantle.

Note that very young birds break this rule and show dark and distinct streaking all over (including the mantle). No need to worry though as these birds do not really look like any of the other species either and still retain the overall shape and structure of the adults! The juvenile plumage is also lost fairly early (usually before the wintering birds arrive) and it’s highly unlikely to see a migratory species in its juvenile plumage.

Paddyfield Pipits: Both birds (L – SW Coast, R – Bengaluru) are juveniles as is evident by fleshy bases to the gape. The streaking is varied in both cases with one bird (L) showing contrast with white edges to new feathers and the other (R) showing buffy edges. Both have streaked mantles. But the overall structure of both birds is typical of a Paddyfield Pipit. Photo: Rahul Narlanka (L), Aravind AM (R)

2.c. Median coverts

Paddyfield Pipit: The above bird from Pune is compact, with a well marked face and has median coverts which are typical of a Paddyfield Pipit. Photo: Sneha Gupta

It is worth noting the centres to the median coverts on pipits in the field. Learning to do so often takes some practice, but with experience one can latch on to differences with fewer difficulties. The median coverts of all the mentioned pipits are bordered by a pale colour with a dark shape in the centre. The shape and the contrast between the colour of the centre and the border are relevant to identification.

To put this in context with other species, the Paddyfield Pipit’s median coverts are bounded by a relatively mild buffy border that does not contrast strongly with the centres to the median coverts. In the Blyth’s Pipit, for example, the almost white border contrasts so strongly that it appears like the bird has wing-bars.

(L to R) Paddyfield Pipit’s median coverts with slightly pointed patches in the centre and buffy edges, Richard’s Pipit’s median coverts with very pointy patches in the centre and buffy edges, Blyth’s Pipit’s covert with squarish patches in the centre and pale edges. Photo: Ramit Singal

Additionally, the shape of the dark centres of the median coverts in Paddyfield Pipits are not very pointy and nor are they squarish. They are, in contrast, very pointy in a Richard’s Pipit and quite squarish in a Blyth’s Pipit.

Caveat: 1st winter birds usually have very variable median covert patterns and contrasts, and it is best to ignore this feature if those are the birds you’re dealing with. You can usually tell a 1st winter bird by it’s mottled, overly streaked plumage (often showing streaking in places where adults wouldn’t show any!) and fleshy gape (base of the bill).

3. Calls

You’ll notice that the font size for the calls header is bigger than the other headers. Well, when it comes to identifying birds in the field – the call is often the first (and most important) clue an observer will get to a bird’s identity. And it is pretty much the only aspect that doesn’t require close views of the bird!

The larger pipits are rather vocal and can possess a surprisingly large repertoire of calls. This is why the summer is a great time to get to know the calls of the Paddyfield Pipits better lest you come across a call that may sound different but is actually a Paddyfield Pipit (or vice versa!).

Most of the Paddyfield Pipits’ calls are sharp single notes usually sounding like a “chip” or “chup”. Sometimes, two notes are delivered together and sound a bit like a “sipsip” or a “tsit-it”. The Paddyfield Pipits also indulge in a display flight (which involves hovering over their grassy habitats with quivering wings) and deliver a song when doing so. This sounds like a hard, buzzy rattling “click-click-click-…” or a “sip-sip-sip…” often recalling the song of a prinia.

Here is an example of a typical display song:

Here is another example, this time of a slightly different display song:

Here is the typical call, changing from a distinct single note to double notes as the bird takes to the wing:

Note:

All of the features mentioned above are best used in a combination and not in isolation, since neither is diagnostic by itself. If a bird shows most of the mentioned features then it is probably a Paddyfield Pipit.

The article might or might not clarify pipits for you. But experienced observers will often reinforce that the best way to learn how to identify pipits is to go out and observe them as much as possible!

Take photos, record sounds and notice the nuances in plumage, posture and behaviour and you’re bound to pick up patterns that are unique to the species you are observing. There is no better time to observe the most common species from the one of the most confusing groups of birds in our region than the non-migratory season (because this is a resident species, unlike it’s similar looking cousins) and everyone is encouraged to find a patch of suitable habitat nearby and look for some pipits!

No matter what, some pipits will always escape identification to species level. In that case, do not forget to use pipit sp. if you are entering your sightings on eBird!

For part 2 of the series (identifying Blyth’s and Richard’s Pipits), click here

OMG, the 1st audio clip and more so the 2nd clip, i have heard these calls a lot and always assumed it was a ashy prinia, now i am wondering how many of those calls were pipits actually. Now you have opened up a pandora’s box for me, birding is getting more complicated suddenly. I ID’d my first paddyfield pipit today and the call was more like the 3rd audio clip, clear sighting too, Doddabommasandra lake, bangalore. I read this site to really nail the ID and now you have opened up bigger things for me