This is a guest article by Pritam Baruah. Pritam has been birding around the world for over 18 years. He especially enjoys listening to the extraordinary songs of the resident Northern Mockingbird & Oriental Magpie-Robin at his homes in California & Assam.

Header image: Ibisbills by Prashant Kumar/Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab

What if you were assigned to design a completely new class of vehicle? And you went into your garage, modified your Royal Enfield motorbike with four more tires, some additional shock absorbers and turned it into a fun six-wheel off-roader. What you have now is an oddity, a specimen of a new class of vehicle so to speak, that everyone is excited to have a ride on.

Now that is what happened to just a few species of birds that evolved over time into life forms so different from their nearest relatives that evolutionary biologists place them alone not just in their own genus but in their own families. And if at all close relatives existed in the past, they went extinct, leaving just this one last living representative of a genetic lineage. Basically, such a species would be ‘proof’ that similar organisms might have existed in the past. Families where such species are placed, hence represented by just a single species and single genus, are referred to in this article as ‘monospecific families’. Popularly they are also known as ‘monotypic families’ and it so happens that they get very special attention from birdwatchers and photographers that want to record as many unique families as possible. Sure, some might see this as a weird expression of geekiness but the birding juggernaut can hardly be blamed for its zealous pursuit of such special things as the bizarre Shoebill Balaeniceps rex (Balaenicipitidae) in the papyrus swamps of Uganda and the secretive Rail-babbler Eupetes macrocerus (Eupetidae) in the rainforests of Malaysia.

Photo: Rail Babbler by Saravanan Krishnamurthy/Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab

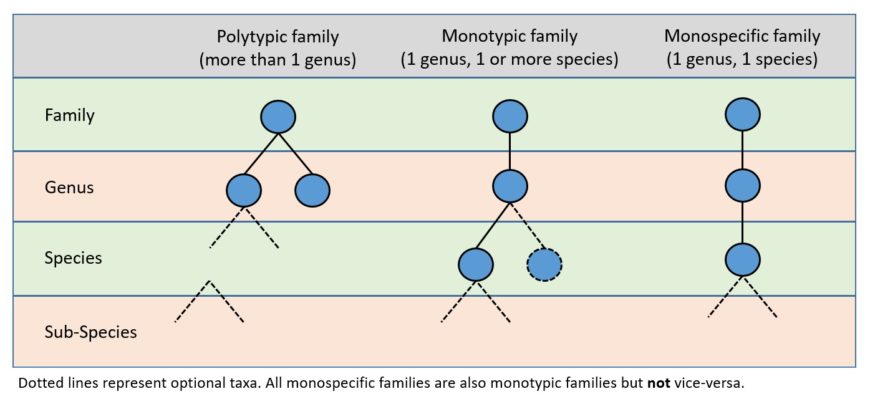

A bit about terminology before we proceed: it should be noted that in formal scientific naming the term ‘monotypic’ is used for a taxon which has only one subordinate taxon at the next taxonomic rank (a node in a tree that has a single outgoing branch). Wherein, a taxon is defined as a formally named group at any taxonomic rank (e.g. family or genus or species). If following this nomenclature, then a ‘monotypic family’ would be a family that has a single genus but not necessarily just a single species. But if so then what should those endearing families consisting entirely of only one species be called? Are the terms ‘unispecific family’ or ‘monospecific family’ more suitable? Perhaps yes, but there doesn’t appear to be any consensus and birders seem to have appropriated the term ‘monotypic family’ to simply mean having one species, albeit a species that can have multiple sub-species. This article instead uses the term ‘monospecific family’ to refer to the same, the term ‘monotypic genus’ to refer to a genus that has only one species and the term ‘monotypic species’ to refer to a species that does not have any sub-species.

Coming up with a list of species that fall into monospecific families is not a simple task though. That is because of two reasons. First, bird taxonomy is continuously changing due to new exploration and new scientific study, especially phylogenetic analysis. Second, there exists several influential lists that describe this ever changing taxonomy. Not unexpectedly, these lists aren’t always in agreement, although most lists now admit to trying for future consistency with each other. For example, Ostrich was considered to be two species (Common & Somali) by IOC since 2008 but HBW and Clements considered it a single species in the family Struthionidae (hence monospecific in both) until 2014 and 2015 respectively, after which both lists ended up splitting it (hence no longer monospecific in all three). Also, until 2014 HBW followed a conservative methodology that tended to lump and hence recognized only 22 monospecific families. But this is a constantly changing taxonomy and it has since added 11 more monospecific families after adopting the criteria described in Tobias et al. (2010). The following table shows the number of world-wide families as of 2017 in four major lists.

| List | Number of families | Monospecific families |

| IOC World Bird List (v 7.3 2017) | 240 | 33 |

| HBW Illustrated Checklist (2016) | 243 | 33 |

| Clements Checklist / eBird (v2017) | 248 | 38 |

| Howard & Moore (4th ed 2014) | 236 | 29 |

So world-wide, an average of about 14% of the families are monospecific. Furthermore, we see that not only are the number of recognized families different in each taxonomy, the number of monospecific families are also different. In this, although both HBW & IOC list 33 monospecific families each, they are not the same set of species.

Confused as to why such discrepancies exist? The simple answer is that there are no formal rules that govern the delimitation of higher order taxa, including the family rank. Although taxonomists evaluate shared morphological and phylogenetic features to group organisms into higher order taxa, the decisions are based on personal judgement. Such discrepancies can arise at the species rank too, because scientists may use different species concepts or even interpret data differently.

So how many of these monospecific families are found in India? India is represented by 7 families that are considered monospecific by at least one of the major taxonomies above. Without further ado, here are the 7 monospecific families that are found in India.

(1) Ibidorhynchidae: Ibisbill Ibidorhyncha struthersii

Ibisbill, Nameri National Park. Photographed by Bikash Kalita ©

This bizarre shorebird is placed in its own family by the first three taxonomies above. Its spectacular looks are surpassed only by its rarity. Not surprisingly it always finds itself in such enumerations as ‘top targets’ or ‘best birds of the trip’. Externally it looks like an evolutionary joke – as if an ibis, a lapwing and a plover got mixed together in a bowl. Genetic analysis (Baker et al. 2007) has placed it close to avocets, stilts (Recurvirostridae) and osytercatchers (Haematopodidae) but it also shows that the Ibisbill lineage separated from osytercatchers in the Eocene, well over a staggering 40 million years ago, which is deeper than many other currently known inter-family divergences, so it clearly merits family status. H&M4 rather conservatively, places it within oystercatchers. It is a monotypic species – that is it does not have any sub-species.

The Ibisbill’s signature deep red decurved bill, black mask, bold chest band and delicate grey feathers make it a stunning species to look at. It’s very specialized habitat requirement – shingle beds along fast flowing Himalayan rivers means that it is highly localized. And since it occurs in low densities, it is overall a tough bird to find, made even harder to spot by its plumage and shape that camouflages well with its rocky surroundings.

Best time to see this is in winters when certain populations descend onto the low Himalayan foothills. The Jia Bhoroli River in Nameri National Park and Kosi River in Jim Corbett National Park are the classic places for this species in winter. In spring and summer, the Indus River near Leh and Sangti Valley near Dirang (where they are resident all year long) are great places to find this species.

(2) Dromadidae: Crab-plover Dromas ardeola

Crab-plover, Kutch. Photographed by Jugal Tiwari ©

This elegant and distinctive looking species is one of the five oddball shorebirds worldwide that are placed in their own families by the taxonomies above (Ibisbill, Magellanic Plover, Egyptian Plover, and Plains-wanderer being the other four). Traditionally it has either been considered close to auks (Alcidae) because it digs its own nesting-burrows in sand, in fact this is the only shorebird to do so, or to terns (Laridae) because of its downy chicks and bill structure. But recent genetic studies have placed it as a shorebird closer to coursers (Glareolidae) than any other family (Pereira & Baker 2010). That’s right, this is not a plover (Charadriidae) at all. It is a monotypic species.

This species breeds almost exclusively in localized colonies on the coasts of the Arabian Peninsula, Iran and northern Somalia. In winter it disperses in small groups to the east coast of Africa, coasts of the Indian peninsula and coasts on both sides of the Andaman Sea. In India the best place to see this is in the coasts surrounding the Gulf of Kutch, especially around the city of Jamnagar, where it is a regular winter visitor in good numbers.

(3) Pandionidae: Osprey Pandion haliaetus

Osprey, Dighal. Photographed by Subhadeep Ghosh ©

This iconic fish eater is one of the most wide ranging species of the world, found in every continent except Antarctica. Its long sharply angled wings and heavy wingbeats produce a labored gliding movement that gives it the signature jizz of a giant bat. Historically, it used to be placed in Accipitridae (hawks, kites, eagles & allies) but most taxonomies converged on recognizing a new family based on its distinct morphology. More recent morphological and genetic studies propose splitting it into three species (Wink et al. 2004) and indeed, IOC has split it into two – populations from Java to Australia as Eastern Osprey P. cristatus and everything else as Western Osprey P. haliaetus. However most other authorities, including HBW, Clements & H&M4 have not accepted this split. There are four recognized sub-species – North American, Caribbean, Palearctic and the aforementioned ‘eastern’ form. The Osprey winters almost all over the interior and coasts of India and is a relatively common sight around undisturbed wetlands and along large rivers.

(4) Upupidae: Common Hoopoe Upupa epops

Eurasian Hoopoe, by Fareed Mohmed/Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab

Easily one of the most recognizable and widespread birds in Eurasia and Africa, its entire population, consisting of roughly 8 to 10 different races, was historically considered to be one species in one family. But starting from the nineties, most taxonomies began splitting it into 2 or 3 species – Eurasian Hoopoe U. epops, African Hoopoe U. africana and Madagascar Hoopoe U. marginata. H&M4 happens to be its last holdout and hence the reason for its presence in this list. The plumage and sound differences between the African and Eurasian populations are rather minor so in recent years there has been a rethink in their species status. HBW recently lumped the African and Eurasian species so it is down from 3 to 2, which is the same treatment as Clements. IOC continues to recognize 3 species.

Overall, the Madagascar form is still considered a full species by most authorities mainly on the strength of its very different song which defies the very name of its genus. Note that ‘Upupa’ is a play on its uup-uup-uup song but in Madagascar the song is a low pitched monotonic trill, which recalls cooing. It can also inhabit dense forest, which is not the case for the other races.

Whatever the taxonomic status might be, there is no denying that this is a unique genetic lineage and nobody can complain that it isn’t a cool bird, what with its bold demeanor, flamboyant crest and ability to breed in the plains all the way up to the high Himalayas above 4000 masl. India holds three widely recognized sub-species and they are an endearing presence in open habitats, cultivations and even in human habitations throughout the country.

(5) Tichodromidae: Wallcreeper Tichodroma muraria

Wallcreeper, Dirang. Photographed by Roon Bhuyan ©

Of the 7 species listed here, this is the only one whose phylogenetic position has been investigated very recently (say within last two years). Traditionally it has been considered closely related either to nuthatches (Sittidae) or treecreepers (Certhiidae). Early genetic studies, along with its high elevation niche and unique internal and external morphology were used to justify family status and two sub-species were recognized. But recent genetic studies have confirmed a close relationship to nuthatches (Zhao et al. 2016) and HBW has not retained family status in its most recent update (del Hoyo & Collar 2016). Instead it is placed in a monotypic sub-family Tichodrominae under family Sittidae. Most other taxonomies excluding H&M4 continue to retain its family status.

In any case, this is a highly sought after bird, full of odd character, crawling along mud walls and shingle banks of fast flowing rivers looking for insects. It is even more dramatic in flight when the large red patches on its wings suddenly become visible. Ladakh is a good place for this species in spring and summer, but the best time to see this is in winters when it spreads out over a more accessible elevational range, from temperate regions to the low foothills. Exposed mud walls and shingle banks near Dirang or Corbett National Park have been reliable for this species in winter.

(6) Hypocoliidae: Grey Hypocolius Hypocolius ampelinus

Hypocolius, Fuley. Photographed by Subhadeep Ghosh ©

At different points of time, studies based on its confusing morphology suggested a bewildering variety of potential relationships – that it may be related to shrikes (Laniidae) or cuckooshrikes (Campephagidae) or thrushes (Turdidae) or bulbuls (Pycnonotidae) or waxwings (Bombycillidae). Quite a mystery! Finally, a recent genetic study has confirmed that it is indeed closer to waxwings (Spellman et al. 2008) than any other family. But its exact relationships still remains unclear so it continues to be placed in its own family by most taxonomies. It is a monotypic species.

So why call it Grey Hypocolius when it sits alone in its own family – isn’t simply Hypocolius sufficient? While this debate rages on, there is no doubt that this is one of the most sought after species in India. Historically this has been a difficult bird to find because almost its entire breeding range is in the politically disturbed countries of Iraq and Iran. Birders used to look for it in the Arabian Peninsula and still do, but in the early 1990s a wintering population was found in the Kutch district of Gujarat (Tiwari 2008), which is located in the eastern extremity of its range. This population has been very regular over the years and small flocks can be reliably seen in suitable habitat. This happens to be the only reliable area in India to find this species.

(7) Elachuridae: Spotted Elachura Elachura formosa

Spotted Elachura, Namdapha NP. Photographed by Jainy Maria ©

This delightful little species, a quintessential skulker of the north-eastern hills was for a long time firmly considered to be a wren-babbler, sharing its genus, Spelaeornis, with 8 other wren-babblers, all distributed in the Eastern Himalayas. But a comprehensive 2014 genetic study (Alström et al. 2014) presented the stunning result that this species is not even closely related to babblers, let alone wren-babblers. In fact, the study exposed a new family altogether, implying there are no close living relatives. Presumably, convergent evolution had made this species look and behave just like wren-babblers because they shared the same ecological niches. This placement was quickly adopted by all taxonomies (note: H&M4’s last update happened just before this paper was published so it does not have this family yet). Currently it is treated as a monotypic species and it remains to be seen if the forms in India and China, separated by the high peaks of the eastern Himalayas would be considered different races.

Spotting this bird as it tries its best to be invisible in the dark forest understory is a challenge that all birders to North-East India will rejoice. Photography is even harder. In fact, it is often heard but not seen. The best places to see this species year-round is in the sub-tropical forests of Mishmi Hills and Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary. The forests around Shillong and Khonoma are also fairly reliable.

Postscript

While the above are the monospecific families currently found in India, are there any other species in India that might get elevated to their own families in the future? For instance, will the White-bellied Erpornis Erpornis zantholeuca, now known to be closely related to vireos (Vireonidae) (Reddy & Cracraft 2007) and not related to babblers (Timaliidae) or yuhinas (Zosteropidae) at all as previously thought, be given its own family? Will there ever be a confirmed record of Bearded Reedling Panurus biarmicus (monospecific in Panuridae) in India? Of course that is impossible to tell now because the future holds yet unknown discoveries and the promise of a better understanding of evolutionary relationships. Until then though, pack your binoculars and go looking for the seven families listed here.

White-bellied Erpornis, Guwahati. Photographed by Chandan Chakravorty ©

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his deepest thanks to Per Alström and Praveen Jayadevan for their thorough review of this document. Their comments greatly benefited this work. The author would also like to express special thanks to Bikash Kalita, Chandan Chakravorty, Fareed Mohmed, Jainy Maria, Jugal Tiwari, Prashant Kumar, Roon Bhuyan, and Subhadeep Ghosh for generously contributing their photos to supplement this article.

References

Wink, M., Sauer-Gürth, H., & Witt, H. H. 2004. Phylogenetic differentiation of the Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) inferred from nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. Raptors Worldwide. Edited by Chancelor, R. D., Meyburg, B. U. WWGBP, Berlin.

Baker, A. J., Pereira, S. L., & Paton, T. A. 2007. Phylogenetic relationships and divergence times of Charadriiformes genera: Multigene evidence for the Cretaceous origin of at least 14 clades of shorebirds. Biology Letters 3:205–209.

Reddy, S., & Cracraft, J. 2007. Old World Shrike-babblers (Pteruthius) belong with New World Vireos (Vireonidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 44: 1352-1357.

Spellman, G. M., Cibois, A., Moyle, R. G., Winker, K., & Barker, F. K. 2008. Clarifying the systematics of an enigmatic avian lineage: what is a bombycillid? Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 49: 1036-1040.

Tiwari, J. K. 2008. Grey Hypocolius Hypocolius ampelinus in Kachchh, Gujarat, India. Indian BIRDS. 4(1): 12–13

Pereira, S. L., & Baker, A. J. 2010. The enigmatic monotypic crab plover Dromas ardeola is closely related to pratincoles and coursers (Aves, Charadriiformes, Glareolidae). Genetics and Molecular Biology. 33. 583-6.

Tobias, J. A., Seddon, N., Spottiswoode, C. N., Pilgrim, J. D., Fishpool, L. D. C., & Collar, N. J. 2010. Quantitative criteria for species delimitation. Ibis. 152: 724–746.

Dickinson, E. C., & Remsen, J. V. Jr. 2013. The Howard & Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World. Fourth Edition. Vol. 1. Non-passerines. Aves Press, Eastbourne, U.K., 461 pp.

Dickinson, E. C., & Remsen, J. V. Jr. 2014. The Howard & Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World. Fourth Edition. Vol. 2. Non-passerines. Aves Press, Eastbourne, U.K., 752 pp.

Alström, P., Hooper, D. M., Liu, Y., Olsson, U., Mohan, D., Gelang, M., Hung, L. M., Zhao, J., Lei, F., & Price, T. D. 2014. Discovery of a relict lineage and monotypic family of passerine birds. Biology Letters, 10: 20131067; https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2013.1067.

del Hoyo, J., & Collar, N. J. 2014. HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World. Volume 1: Non-passerines. Lynx Edicions and BirdLife International, Barcelona, Spain and Cambridge, UK.

del Hoyo, J., & Collar, N. J. 2016. HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World. Volume 2: Passerines. Lynx Edicions and BirdLife International, Barcelona, Spain and Cambridge, UK.

Praveen J., Jayapal, R., & Pittie, A. 2016a. A checklist of the birds of India. Indian BIRDS 11 (5&6): 113–172A.

Zhao, M., Alström, P., Olsson, U., Qu, Y., & Lei, Y. 2016. Phylogenetic position of the Wallcreeper Tichodroma muraria. Journal of Ornithology. 157: 913-918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-016-1340-8.

Gill, F., & Donsker, D. (Eds). 2017. IOC World Bird List (v 7.3).

Clements, J. F., Schulenberg, T. S., Iliff, M. J., Roberson, D., Fredericks, T. A., Sullivan, B. L., & Wood, C. L. 2017. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2017.

A very interesting article! Learnt a lot from this. Thanks a lot for this post.

Great article, Pritam! Best – Vivek T

Extremely useful compilation Sir, thanks for sharing.

However, what is the current status on the Groundpecker?

Hi Rishi, good question. The Groundpecker (now called Ground Tit) is part of the much larger family of tits (Paridae), hence not a monospecific family. However it is unique enough within tits that it gets it own genus (Pseudopodoces).