The eBird Data Quality and Review Process

Summary (tl;dr)

As eBird data is made publicly available for use in research and conservation it is important to ensure data accuracy as far as possible. To accomplish this, eBird uses a review process comprising primarily of manually curated data filters and a network of reviewers communicating with observers by email. If a record uploaded by an observer is flagged as unusual or significant by the regional data filter, the observer is prompted to add more information and a regional reviewer will follow up. If the added information is sufficient, the reviewer does not need to contact the observer; else the observer will receive an email from the reviewer, requesting more information.

When an eBird user receives an email about one of their observations, it means that there is potentially something significant about it: for example, it could be a rare species, a species outside of its normal range, an unusually early or late date for a migrant; or, in a few cases, it could be an error, either because of data entry or misidentification. Regardless of the reason, following up on these observations increases our collective knowledge about birds in India, and improves our birding knowledge and skills.

Based on the documentation accompanying the observation, a reviewer will categorise it as confirmed or unconfirmed.

A confirmed record is one with sufficient documentation to be made available for public use.

An unconfirmed record has insufficient supporting documentation to confirm it “beyond reasonable doubt”. This does not mean that the observation or ID is incorrect — it is an evaluation of the documentation, not just the identity of the species.

The only implication of records being unconfirmed are that they are excluded from public output, such as the eBird species maps and other reports, plus the full dataset available for download. They remain, however, on the checklists of the original observers and are included in their personal lists and reports. And, if new information comes to light, it’s quite possible for a previous unconfirmed record to be marked as confirmed.

We are extremely grateful for the efforts put in by eBird reviewers and users, which together contribute to building a valuable, comprehensive and authoritative resource for information about the status of birds in India.

The rest of this article describes in detail how the review process works.

“Your Emperor Penguin observation in eBird”

Many of you will have received emails like this (admittedly probably not for this species though!) This article is to explain why you receive these, and why you should be pleased when you get one!

Read on, or click on a heading below to jump directly to the section.

Importance of eBird Data Quality

eBird data is made publicly available and is used heavily around the world by the research and conservation communities. This data is used for various purposes, including the designation of new Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBA) and Ramsar sites, contributing to Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) for development projects, as well as many local habitat protection projects. As observers we should try to ensure the highest possible level of data quality so as not to jeopardise such initiatives; in effect, our aim is that any user of eBird data should be able to trust any record that they view.

eBird Data in India

Despite a long history of ornithology in India, it is surprising how little we know about even some of our common birds.

When do Blyth’s Reed Warblers arrive in the autumn?

How many Garganeys are normal in November?

Are Little Swift numbers similar year-round or do some migrate?

What are the year-to-year changes in the bird life in my region?

How has the abundance of Indian Rollers been changing over time?

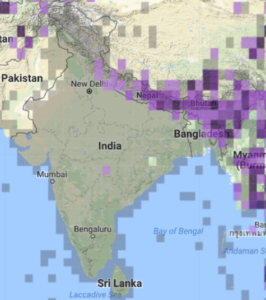

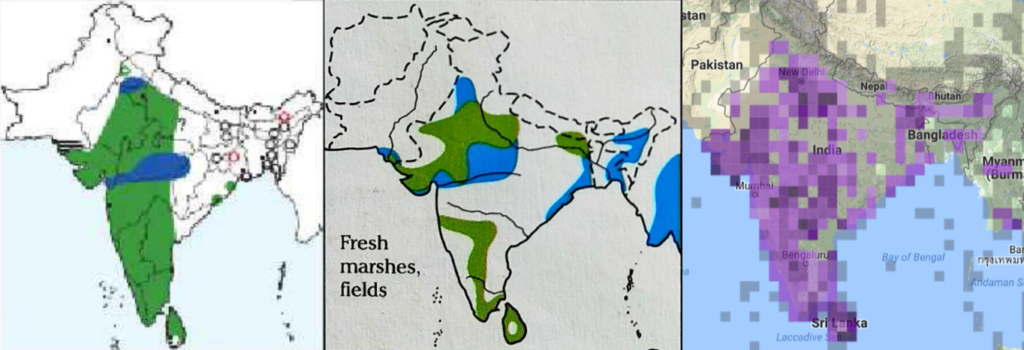

Field guides in India provide maps for distribution, with some notes about seasonality and status. However, these have often been based on the author’s opinion, or historical records, and include some level of guesswork. In some cases, the large number of observations in eBird can already tell us better information: for example, compare the distributions of Black-headed Ibis and Black-breasted Weaver from various field guides with the eBird maps.

Black-headed Ibis distribution

(left to right: Rasmussen and Anderton; Grimmett, Inskipp and Inskipp; eBird)

Note that while one field guide includes a contiguous north-south range in western India, and one shows presence, in the east and north-east, only the eBird map confirms both of these

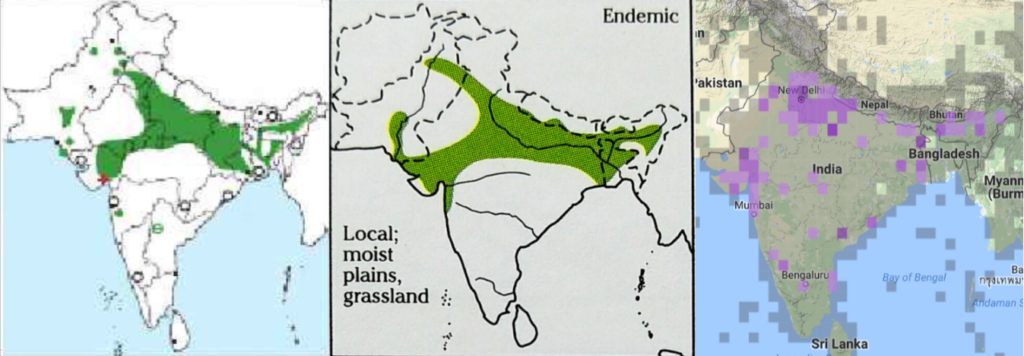

Black-breasted Weaver distribution

(left to right: Rasmussen and Anderton; Grimmett, Inskipp and Inskipp; eBird)

Note especially the presence in the south and centre as depicted by eBird but neither field guide

How can we have confidence that the eBird maps are more accurate?

Data Errors

As with any large-scale citizen-science project, there is always the possibility that erroneous data will be entered. With eBird this could be for many different reasons, aside from actual misidentifications, a few of which are listed below:

- simple typing errors, e.g. entering 100 instead of 10

- selecting the wrong species by being confused with names; e.g. Common Cuckoo instead of Asian Koel

Asian Koel – a common cuckoo, but not a Common Cuckoo!

© Savio Fonseca - personally knowing birds by different names to the standard names used in eBird, and therefore not finding the species you were expecting and selecting another that seems correct; e.g. looking for Common Goldenback and using Common Flameback instead when Black-rumped Flameback is actually the required species

- selecting an unintended species when using eBird short codes; e.g. Grey Wagtail instead of Greenish Warbler (both of which use the same eBird short code of ‘GRWA’)

- having eBird preferences not set to English (India) and therefore showing international names instead of familiar Indian ones, and consequently selecting the wrong species; e.g. Plain Martin instead of Grey-throated Martin

- selecting the wrong species when using the eBird mobile app, due to the difficulty of being precise, especially for those with large fingers!

- actually seeing an unusual species, but having doubts because it is not on the checklist and selecting another one that is (instead of using “Add Species” to select from all other possibilities)

- inadvertently entering incorrect dates, times, or using the incorrect eBird protocol

- entering a complete species list when it is meant to be incomplete

- combining lists from multiple different locations into a single list, which can lead to misleading analysis with species plotted at the wrong map locations for example

These errors can easily result in observations being submitted to eBird that seem to be of birds that are very rare, are out of their normal range, are early or late compared to their expected migration dates, or are seen in much larger numbers than expected. Of course, rare birds do turn up, birds do appear in unexpected places or unseasonal times, or in unusually high numbers. So how do we distinguish the errors from the unusual?

In order to distinguish potentially significant records, and ensure they are supported by adequate documentation, from potential errors, eBird uses a review process.

eBird Review Process

To ensure a high degree of data quality, eBird employs two main methods of “review”:

- Data filters – these are manually curated, and thereafter, automatically check for an observation against predefined thresholds for the species, indicating whether it is potentially significant for the location, date and count recorded

- Manual review, in collaboration with the observer and a network of eBird reviewers, to gain more information to help confirm the sighting

Every single observation entered in eBird, regardless of who submits it, goes through the same verification process.

The result of this process is that every observation is either Confirmed or Unconfirmed.

A confirmed record is one that is sufficiently documented to be made available for public use. This means that the record will be included in all eBird maps, seasonality charts and other reports, plus available in the complete datasets that are downloadable for further use by anyone. This will include records that are “regular”, and not flagged by the data filters, as well as ones that were flagged and have been marked as confirmed based on subsequent review communication between an eBird reviewer and the original observer.

An unconfirmed record is one that is insufficiently documented to be made available for public use. Note that this does not necessarily mean that there is anything wrong with the record, but purely means that the details supporting the observation are insufficient to confirm it “beyond reasonable doubt”, and therefore it should not be put on public record to be used for further research or conservation purposes. This will include records that were flagged by the data filter and are still insufficiently documented in eBird after any communication between the reviewers and observers. It also includes records that are imprecisely located – there may be no doubt about the observation itself, but if the location covered a large geographical area (eg a District) then the record could not be plotted on a map with sufficient accuracy. Although unconfirmed records do not appear in eBird maps and reports, or the publicly available dataset, they still remain in all the observer’s records and lists: there is actually no difference between a confirmed and unconfirmed record for the observer personally. In addition, the status of a record can change from unconfirmed to confirmed if additional evidence comes to light.

As mentioned above, because eBird data is increasingly being used for science and conservation, we have an obligation to try to ensure accurate data. The process for review is intentionally cautious, which means that reviewers are asked to be more worried about possible false positives (confirming a record which is possibly incorrect) than possible false negatives (leaving a correct record unconfirmed). This ensures that publicly available data, such as the species maps, can largely be trusted. Confirmed records should stand the test of time, so a user in future years can have confidence in the data.

Filters

The base for the review process are eBird filters. A filter defines:

- The list of species options displayed when you enter a list in eBird, using the website or the app

- Which records are considered potentially unusual and therefore flagged for manual review

A filter is defined for a geographical area. Across much of India these are at state level, but in more popular areas, and places where our understanding of species status is better, they are defined for smaller and more precise areas.

Each filter enables automated detection of records that potentially involve:

- species that are not known to occur in the area

- unusually high counts of species that do occur in the area

- rare species, or species of conservation importance

- species that appear during seasons when they are not expected

- an unusual species that can be easily confused with a common species

Each filter defines, for each species, an “expected” total count threshold for a birding session at a location within the filter’s area on a given date. Any record that exceeds the expected total will be flagged for manual review.

If the total on the filter is zero, then the species is considered “Rare” (better thought of as “noteworthy”) and will only be shown on the data entry checklist if “Show rare species” is checked.

The diagram below shows how a filter has been set for Northern Pintail. Expected totals peak in mid-winter and decline gradually through March to May, with none expected (“Rare”) until September, when numbers increase through the autumn. As an example, an observation of 250 Pintails on 10 March would be automatically confirmed, but the same number on 20 March would be flagged for manual review, and any over-summering Pintail would also be flagged.

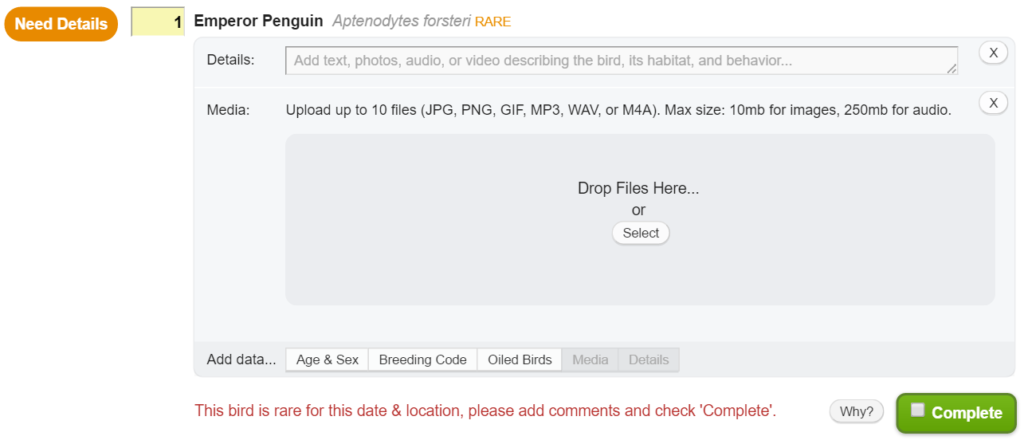

When you submit a checklist on eBird the filter processes your observations and, for any species that are either not present on the filter or exceed the filter thresholds, and are therefore considered noteworthy, you are prompted to add some documentation.

The message given will say whether the species is considered rare for the date or location, or is an unusually high count. If you see this prompt, please double-check that you are entering the correct species, and then add any supporting details you can, e.g. circumstances of the observation, how you identified the species and distinguished it from other similar species, how you counted or estimated. (Read more about how to write an account for a rare sighting.) Your observation will then be considered unconfirmed pending a manual review by eBird reviewers, and will not show in any public output until this review is done.

Often it is not easy to add extra details at the time, e.g. if you are using the eBird mobile app and it is inconvenient to write much, or if you have photos that you haven’t yet processed. You can certainly add a note to say something like “Details/Photos to be added later” (or even “tbc” if you want to keep it quick), but please do indeed follow-up later!

Filters are set by volunteer eBird editors who have a good understanding of species status within their regions. They are adjusted regularly based on analysis of eBird records: for example, if there were several flagged records of Pintails in late March that were considered confirmed through manual review, the editor might decide to extend the period where 200 is the threshold to the end of the month, or increase the threshold to 300 say, or even make both changes.

One difficulty with setting filters is when the geographical area covers a wide variety of habitats, potentially across large distances. For example, setting a filter for Bar-tailed Godwit ideally requires very different thresholds for the coast compared to inland. Whilst separate filters can be created this requires considerably more effort to maintain, so often a compromise is required: the filter could be set with inland thresholds which would result in several coastal records being flagged, and more work in manual review, but would avoid notable records being undetected.

The large area covered by a filter is the explanation for one of the most common questions from eBirders, i.e. “why has my record of <species> been flagged as it is not rare here?” The answer is that it may well not be rare in the precise site where the observer was birding, but it is not uniformly common across the entire area that the filter covers. With the Bar-tailed Godwit example, the filter editor may well set the filter to zero, so that every inland record would be flagged and there would be no risk at all of erroneous/noteworthy records getting automatically validated. The downside of this is that a birder on the coast, seeing Bar-tailed Godwit regularly, will get every record flagged (and hence will be prompted to add additional details each time). You can just enter a brief comment such as “Common here” each time and, once the reviewer is aware of this, they will be able to validate further sightings without the need to contact you.

At the time of writing India has nearly 70 separate filters, and this will increase as eBird usage increases, and consequently our detailed knowledge of species status regionally.

Manual Review

Review of flagged records is handled by a network of volunteer eBird reviewers, who are eBird users themselves, and have good knowledge of birds within the regions they are set up to review. All areas in India have multiple reviewers assigned, so don’t be surprised to find yourself communicating with different people from time to time.

Reviewers investigate all flagged records, based on the notes provided by the observer, checking eBird species maps and seasonality charts, referring to field guides and other literature, conferring with other reviewers and knowledgeable birders etc., in order to try to determine whether the observation is sufficiently documented to be used as a public record. Often they will confirm a record fairly easily; based on the examples above, a coastal Bar-tailed Godwit, or a Pintail flock just exceeding the threshold, might be marked as confirmed from this information. In many cases though they will request further information, and will do this by emailing the original observers.

Reviewers often have a large number of records to process, so a standard email is used to save time, however they do usually add a specific comment giving more reasons why your particular observation is significant. Obviously it could be a rare species, but it might be that it is an unusually high count, or an extra early or late record of a migrant. In some circumstances you might not consider the record to be particularly significant yourself – maybe you regularly see the particular species at this location, or the sort of numbers you have reported. In cases like this it is still noteworthy as it means overall we didn’t know that the record was quite regular, and your reporting it has helped fill a gap in our collective knowledge. Over time, with a few such regular records, the eBird editors will change the filter thresholds defined for the region so that our knowledge is updated, and similar records reported in the future will no longer be flagged.

Note that a record flagged for manual review, but not yet investigated by a reviewer, will also be treated as Unconfirmed, and hence not appear on maps. In some regions of India, particularly where lots of historical records have been uploaded, it may take some time for reviewers to get around to processing all flagged records.

How to Deal with an Email Query

Reviewers cannot themselves change, edit, or delete records. Therefore observations that have an email request sent for details will remain unconfirmed until you yourself amend the observation on your eBird checklist and the reviewer revisits it.

When you receive an email from a reviewer, firstly please realise that it is because there might be something significant about your record, and information is being requested in order to confirm it for it to be made available for public use. Typically, you then have the following options:

- You can ignore the email – this is actually fine (although an email response is preferred even if it just says that you can’t remember, have no details to add, or don’t have time to address it). The only implication of this is that the observation will remain unconfirmed and won’t be on public record, so will not be used for any research or analysis. It will always remain in your personal account, and appear on your checklists, unless you change it.

- You can change the eBird record yourself – this could be adding details, such as the circumstances, a description of the bird, photo, details of how you counted; or it could be the removal of the species if you decide it may not have been correct, with maybe the addition of the correct species, or an appropriate spuh or slash. Note that photos are helpful but certainly not mandatory – an account of the sighting always adds context even where photos are available, and good field notes are often sufficient. Please also reply to the original email, so that the reviewer knows you have made a change and can check the additional details.

If you are unsure, e.g. of the identification, do discuss with the reviewer, who may also consult with other people depending on the expertise required, and hopefully will be able to help reach a conclusion. Please do ensure that you also update the eBird record, so that details are not just kept in the email correspondence and are instead visible to anyone using eBird data in the future.

eBird is used by all levels of birdwatchers from complete beginner to experienced ornithologist, from those who watch birds only in their garden to those who have travelled the world. As far as possible though, reviewers are asked to assess records objectively based on the details given in eBird, or subsequent correspondence with the observer. Those who provide clear and detailed accounts, and respond promptly, will inevitably gain a reputation as scrupulous eBirders who appreciate the importance of data quality and review. Those who enter little detail (e.g. comments such as “seen well”, “heard calling”, “confirmed”, “possibly more”, “ID confirmed by experts”) or do not respond to queries, are likely to find that more of their records remain unconfirmed.

Reviewers certainly find that being involved in the process helps them improve their own skills in bird identification and knowledge of species status, and do their best to build good relationships with observers, helping them improve their birding and eBirding skills as well.

Sometimes, it will happen that you are convinced that your observation was correct, but the reviewer feels that the documentation available (field notes, photos etc.) is insufficient for an unusual sighting to be used publicly. To ensure accuracy of data, reviews are asked to err on the cautious side; do remember that anything you submit will still remain in your personal account and appear on your checklists, whether confirmed or unconfirmed. We recognise that this can be frustrating if you have a correctly-identified bird excluded from public use, but we hope that the wider research and conservation goals are understood and appreciated by all. Being questioned about a record is not personal – it is simply a request for more information so that your record will stand the test of time. It is almost certain that all eBirders, including those with many years of birding experienced, will have some observations that remain unconfirmed.

Re-Review and Ad-hoc Review

One great advantage of a dynamic and up to date database such as eBird, when compared with a book or other publication, is that it is easy to revisit assessments in the future. Further records of a species in an area may provide more evidence of a pattern that could make it possible to confirm earlier unconfirmed records. As an example, because reviewers err on the side of caution, extremely early or late migrant records that may well be correct, are often left unconfirmed because they have insufficient supporting documentation. Over time, with more data coming in to eBird, we may see more “extreme” dates for these migrants, including some with sufficient documentation. Reviewers can then reassess earlier records based on this updated knowledge.

One of the most difficult areas of review is for species that are genuinely difficult to identify, often not adequately covered in field guides, and particularly where the level of detail required to confirm observations beyond reasonable doubt is almost impossible to achieve with normal field views and even photographs. Well-known examples include distinguishing between female Common and Rain Quails, Sand Martin and Pale Martins, Hume’s and Lesser Whitethroats: if records are flagged because of the filter settings, it is unlikely that the details that the observer could add can really be sufficient to confirm them satisfactorily. In these cases, reviewers may confirm more borderline cases, so that records are publicly available for any person worldwide to investigate in more detail, hopefully furthering our overall knowledge. Similarly, a reviewer, having researched themselves (and feeling up to the challenge!), may undertake an ad-hoc review of a single species, or group of species, potentially country-wide. This means that observers may get contacted about sightings that were not flagged originally, and potentially a long time after the actual sighting – please do your best to help out the reviewer with any requested information, and hence help further our collective knowledge.

Dealing with Errors

Despite the various effort described so far, some errors will inevitably go undetected. For example, in areas where in-depth knowledge of species status is lacking, maybe a filter threshold is set higher than it should be, resulting in records not getting flagged and hence not seen by a reviewer. Also, filters cannot detect all possible error cases, such as when two very similar species are regular in the region, and could easily be misidentified – Little and Indian Cormorants, Montagu’s and Pallid Harriers, Golden-fronted and Jerdon’s Leafbirds, Booted and Sykes’s Warblers, are all good examples.

Because of this, eBird editors also use the tools provided by eBird to detect these for further investigation. The bar charts are great for highlighting potentially out-of-season records, the species maps for out of range species, and the photo and sound search for misidentified ones. These tools are available to everyone, so if you think you have spotted an error that a reviewer should check, please contact us with details. (In time, eBird will introduce better functionality to enable you to report potential errors directly.)

Conclusion

Congratulations if you have managed to get this far! We hope this article has given you a good understanding of the importance of the review process, and the practicalities. If you have any unanswered questions, then please contact us and we will update this article accordingly.

In less than three years since the launch of eBird India all of us collectively have built up an incredible database of over four million observations, which should prove invaluable in improving our knowledge of India’s birds, and helping initiatives to protect them and their habitats. We are very grateful for the dedication and hard work put in by the team of eBird editors in order to make this such an authoritative resource, but of course none of this would be possible without the efforts of all you eBirders in India. Many thanks to each of you, and do keep eBirding!

Further Information

- eBird Review Standards – eBird’s article summarising key aspects of review

- Understanding the eBird review and data quality process – eBird’s detailed article explaining the entire review process

- Review Tool and Filter Instructions – eBird’s detailed manual for editors and reviewers, but available for all to read

- eBird guidelines for how to describe rarities, and two articles about how to count birds (counting 101 and counting 201)

Header Image: Himalayan Rubythroat Calliope pectoralis © Rajneesh Suvarna/ Macaulay Library