This is a guest post by G. Parameswaran, R. Sivashankar, and Vridhi. R – members of the Perur Lake Forum (a group of birders who systematically monitor wetlands in Coimbatore). It is a summarised version of their publication, “Rapid decline of waterbirds in urban wetlands: A case study from Perur-Sundakamuthur Lake, Coimbatore,Tamil Nadu, India,” published in Indian Birds (download here). This is the second guest post by the authors, and the first one can be seen here.

My first visit to Perur-Sundakamuthur Lake, or Perur Lake, located in southwest Coimbatore, was in early 2012, whose approach I distinctly remember was through a muddy footpath on which two-wheelers traversed with great caution. The wetland itself was crescent-shaped and moderate in size, having only around one square kilometre as its water-spread area. Its quiet surroundings were bordered by a cluster of trees on its southern side and farmland on its western border. With the absence of sewer or industrial discharge, it was an ideal place to watch birds and engage in restorative recreation. Eventually, a single-lane road was built in early 2014 along its northern perimeter.

After returning from the USA, I spent two years of birdwatching from 2011 to 2013 in the Coimbatore Metropolitan area, which is rich in biodiversity (more than 400 species according to eBird). I then decided that Perur Lake would be an ideal location to start a monthly bird count and thereby initiated a community science programme in Coimbatore. The counting began in earnest in March 2014 with the help of dedicated volunteers drawn from various walks of life, like Sai Vivek (an architect), Dilip Joshi (a retired architect), R. Sivashankar (a mechanical engineer), Vridhi. R. (a software specialist), and many others. Our group, called Perur Lake Forum, organically came into existence and is currently in its tenth year.

The first two years of our bird monitoring from May 2014 to April 2016 were serene because the monsoon rains were predictable and birds were seen at their expected time frames. A summary of their status was published in the Journal of Threatened Taxa

From 2016 onwards, monsoon rains became scarce, and seasonal wetlands like Perur Lake felt the brunt and became totally dry in mid-2017. This provided the opportune moment for the authorities to carry out extensive sand mining operations (see Fig 1), covering 70% of the wetland area and disfiguring this bird-friendly ecosystem. The gently sloping wetland that nurtured a combination of residents and migrant waterbirds was transformed into an unfriendly location with deep pits and valleys. When the monsoon rains returned, a commercial fishing operation was also put in place with the help of nets that crisscrossed the wetland. Finally, the wetland suffered further disturbance in the form of road expansion, the removal of vegetation, and encroachment (see Fig 2), along with the building of a containment wall.

The cumulative results of these human actions, executed with little regard for its ecological consequences, are published in this edition of Indian Birds.

Fig 1: Sand Minding at the Perur Lake. Photo by G. Parameswaran

Fig 2: Building of a Containment Wall at Perur Lake. Photo by G. Parameswaran

In a summary of our results on common waterbirds, the primary emphasis in our study is stated as follows:

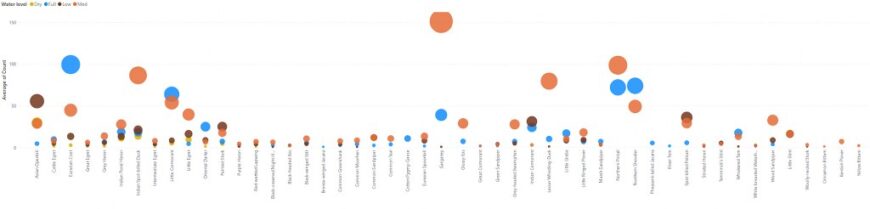

From May 2014 to April 2020, the status and population trends of 125 species were analysed. Of the 49 waterbirds recorded, 29 of them are present in high numbers when the water level is medium. Also, about 80% of the shorebirds are present only during the aforesaid condition, feeding on the moist mudflats. We also found that the abundance of 23 waterbird species, which is 47% of the waterbird species recorded in Perur Lake, dropped significantly during this period. Of the 12 representative waterbirds that were analysed, eight species are categorised as ‘Gravely Impacted’ and four as ‘Highly Impacted’.

Fig 3: Scattered Plot of Wetland Birds Found at Different Water Levels. Image by R. Sivashankar. Click here for high res. image

Fig 4: Little Egret at Perur Lake. Photo by G. Parameswaran

Fig 5: Lesser Whitsling Duck at Perur Lake. Photo by G. Parameswaran

The irony of Perur Lake’s history is that it was once actively considered a possible “Bird Sanctuary” site. If this designation had been achieved in a timely manner, then the subsequent unregulated resource extraction actions like sand mining could have been prevented. The end result is that it is currently in a state where sightings of winter migrant ducks and shorebirds are either scarce or nonexistent. The opportunity cost to the general public is immeasurable because what was once a place for passive and quiet recreation is now a busy transportation corridor.

As I am writing this narrative, I would be remiss in my duty if I failed to mention the current tragic floods in Chennai due to the rains from cyclone Michaung. Among the multiple reasons for this sorry predicament is the steady disappearance of flood-controlling wetlands, which numbered around 600 a couple of decades ago and are currently around 30. Wetlands not only provide a safe harbour for birds and wildlife by conserving biodiversity, but they also simultaneously store water for agriculture, provide flood control, enable water purification, and ground water recharge, to name a few. It is not an either-or situation, where one use or activity can be preferred at the cost of others, but a delicate balance. An ecologically healthy wetland where birds and wildlife thrive is a boon to society because it maintains that ecological balance.

India is currently home to 17.8% of the world’s population, living in an area of only 2.42% of the Earth’s surface. Therefore, even a small loss of wetland area has a larger impact on the country. As bird enthusiasts interested in conservation, it is imperative that hobbyists like us do not shy away from stating the obvious: uncontrolled land use or resource extraction will eventually lead to tragic consequences like the ones that are currently taking place in Chennai. We urge the administrative institutions, whether national, state, or local, to manage our wetlands as responsible stewards rather than enablers for unsustainable resource extraction that seriously disrupts their ecosystem. We also encourage bird enthusiasts to undertake systematic surveys of regular and frequent periodicity to monitor the health of wetlands in our country. Only by instituting such synchronous surveys can one hope to conserve our wetlands for future generations.

Header Image: Asian Openbill Anastomus oscitans by G Parameswaran/ Macaulay Library

Great insights. Hope the concerned authorities take note and preventive action is taken. Best Wishes.

Beautification of lakes with huge fund allocation had spoiled the lakes of Coimbatore. Inturn, polluters, encroachers and smugglers need to be punished now and then.

Hi

i am looking for contact details for the authors. Would be great if you could share the same on the email. This is for a seminar.

Hi,

Please contact G. Parameswaran at