“Finding a rare bird for a region or country gives a birding dopamine kick to birders. The extent of dosage is directly proportional to the rarity index of the bird being sighted. While luck often plays a massive role in sighting first records for a state or country, India continues to hold many birds which are literally ‘sitting ducks’ for those willing to tread into the unknown”. – Says Harish Thangaraj, an avid birder and photographer from India.

This Bird Count India article describes 20 such birds extreme Indian rarities for India, many of which have already been established as regulars for India in the years since this article was written.

Read on about Harish Thangaraj and Sudhir Paul’s quest of finding one of India’s rarest woodpeckers, hidden within a rugged, arid landscape near fortified borders—an area seldom visited by birders. Their remarkable find marks only the second photographic record of this elusive species in India!

Historical Records and the Quest for the Rare Woodpecker

Records of this bird within India’s boundaries are few and far between. The earliest records date back to the 20th century, with one bird each from Fazilka and Arniwala, in Punjab—both specimens preserved at the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London. More than a century later, in 2011, a team from Wildlife Institute of India (WII) reported another confirmed sighting while exploring potential cheetah introduction sites near Dhanana in western Rajasthan. Then in October 2012, Uras Khan, a bird guide from Desert National Park in Jaisalmer, claimed to have spotted four individuals of this species in a single morning alongside another birder. However, no photographs were taken to document these sightings, and the record is not available in the public domain.

Curious about this claim—especially since the only confirmed sighting of this bird in India in the 21st century was 14 years ago—Sudhir and I set out to investigate whether it could still be found in the country. Its status in India was poorly known as the international border area along the states of Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Punjab is heavily fortified and hence, inaccessible to birders for exploration.

This article describes our experience in finding one of India’s rarest woodpeckers: the Sind Woodpecker.

Year 1912—Specimens of Sind Woodpeckers from Fazilka and Arniwala, Punjab—Dorsal View (Preserved at the NHM, London). Photo by Praveen J.

Year 1912—Specimens of Sind Woodpeckers from Fazilka and Arniwala, Punjab—Dorsal View (Preserved at the NHM, London). Photo by Praveen J.

The Sind Woodpecker (Dendrocopos assimilis) is a striking medium-sized woodpecker from the Pied Woodpecker family. Its a woodpecker of arid habitats ranging from Iran to Pakistan. Although widespread in Pakistan, its status in India is poorly known as the international border area along the states of Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Punjab is heavily fortified and hence, inaccessible to birders for exploration.

Expedition Preparations in the Arid Landscapes of Jaisalmer

In February 2025, Sudhir and myself set out to seek this bird in the arid landscapes of Jaisalmer. The region we planned to explore lies right by the international border along Pakistan—restricted area requiring permissions for nature exploration.

Preparations prior to our visit were on multiple fronts: analysing cross-border social media records, searching online for suitable habitats, consulting with experts, and securing permissions. I reviewed the digital media records on eBird and cross-referenced them with known habitats from Pakistan and Iran using Google Earth.

The majority of sightings were from the Indus Basin region which spans over 5,00,000 sq km and is home to 80% of Pakistan’s population. A few scattered records from brown, arid regions gave us hope, as these habitats resembled the area near Dhanana. The site close to the 2011 sighting appeared ideal – a blend of suitable habitat with deciduous trees extending across the border, combined with easy road access. We anticipated minimal habitat destruction here unless military defence-related activities had affected the vegetation.

We also checked the Facebook group ‘Wildlife of Pakistan’ for any photographic records of this species near the Indian border that might not be listed on eBird. Besides, this gave us some insights into the types of trees where the bird had been photographed.

Further, discussions with Praveen J. and Shashank Dalvi provided valuable information in our search for this bird. Shashank had not attempted to find this bird in Rajasthan, he had tried for it at Firozpur, Punjab during his Big Year quest. The overall habitat had undergone significant changes over the years, influenced by the introduction of a perennial water supply from the Indira Gandhi irrigation canals. Praveen suggested that between Punjab and Rajasthan—both areas where this species had been recorded—Rajasthan offered the best chance for a sighting. Praveen also shared a voice note from Anant Pande, who was part of the WII team that sighted the bird in 2011.

Combining digital research and insights from experts, we planned to search for the Sind Woodpecker along the Murar-Dhanana stretch during the 1st week of February 2025. However, I had also learned that recent discreet attempts to find the bird there had been unsuccessful. As a backup, we planned to move further north towards Tanot-Longewala on day two, if needed.

Sudhir approached the relevant Border Security Force (BSF) authorities for the necessary permissions. While we were tempted to attempt the search without Uras in the preceding week, we chose to align with Uras’s availability and reached Jaisalmer on 6 February. This decision would later prove beneficial, as it will help future birders’ attempt to find the Sind Woodpecker with the support of a local contact.

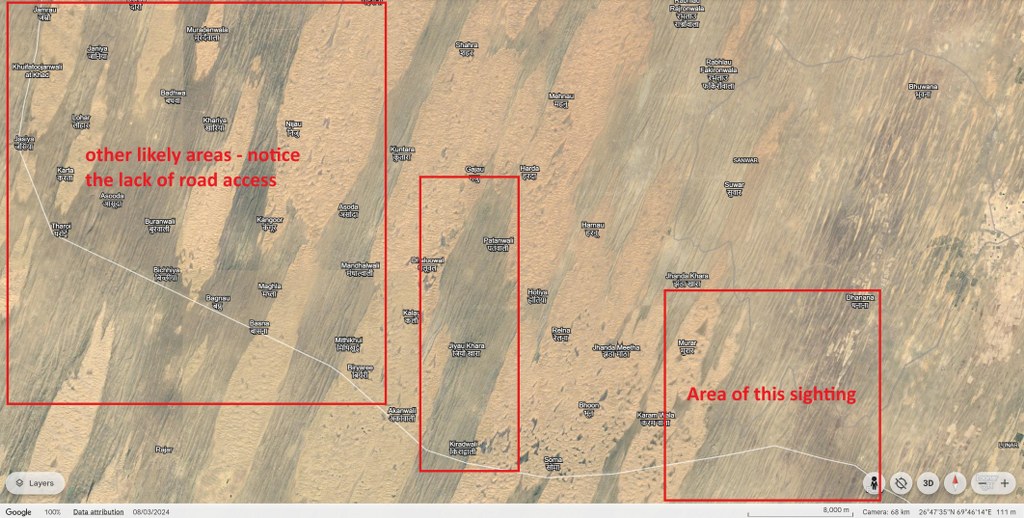

Potential Sind Woodpecker habitats in Rajasthan, marked on a Google Earth map by Harish Thangaraj. The right box indicates the confirmed sighting location, while the left boxes show other likely areas with limited road access.

Field Encounter at Dawn in the Dhanana-Murar Area

On 7th February, in the Dhanana-Murar area of western Rajasthan, we reached the designated spot an hour ahead of schedule and waited for the first light to break. The presence of trees like Prosopis cineraria (Khejri) and Salvadora spp with their aged, peeling bark in the barren desert suggested that we were indeed on the right track in our quest.

Logically, this was the only belt with these tree species, accessible by road, that could support a woodpecker population in this part of the desert. Trees were virtually absent along long stretches of the road, making this area the most viable habitat. Although Google Earth had shown a continuous treeline, the actual contiguity of this Khejri patch with the adjacent area across the border remained unknown.

The two species of Salvadora found in northwestern Indian desert region, are generally recognised as Salvadora persica (Khara Jaal or Miswak) and Salvadora oleoides (Meethi Jaal or Pilu).

Habitat showing prominent Khejri tree (Prosopis cineraria) with its twisted trunk and sprawling branches. Photo by Sudhir Paul.

Once we reached this patch, we initiated systematic playbacks, our hearts pounding with anticipation. After about 45 minutes, I saw a bird flying overhead with the typical woodpecker-like undulating flight, alternating between rapid flapping and brief gliding. I urgently called out to Sudhir and Uras, who had spread out in search, and to our delight, we realised we had found it: a Sind Woodpecker!

The bird, an adult male, boldly perched on a thin Khejri branch. Identification was straightforward—its clean white forehead, cheeks, and underparts; red on the vent extending slightly to the underbelly; and a prominent white patch on the shoulders continuing to the scapulars.

Sind Woodpecker (male) perched on a Khejri tree trunk. Photo by Harish Thangaraj.

The bird remained on the treetops, moving from branch to branch, for the next half hour as we rejoiced at our find. Then, it took a long flight away, settling on a distant branch—and to our astonishment, it was soon joined by another individual, a female!

Due to the sparse tree coverage in the area, the pair occasionally perched in shrubs below eye level, offering excellent opportunities for photographs.

We watched the pair until the sun rose higher and the harsh light and heat made standing in the sand unbearable, before moving on to explore the area further from the comfort of our vehicle.

Pair of male and female Sind Woodpeckers. Photo by Sudhir Paul.

Female Sind Woodpecker—Unlike the male, the female lacks a red crown but retains distinctive markings on its wings and face. Photo by Sudhir Paul.

Finding the Bird in India

Habitat Overview

The area where the bird was sighted lay among sand dunes, separated by sandy gaps with sparse tree cover—roughly 15-20 trees per 100 sq.m. Estimates from Google Earth indicated that the suitable habitat spanned about 1.5 sq.km within Indian boundaries. Khejri and Jaal trees dominated the landscape, spaced roughly 20 to 30 feet apart. The population of this species appears to be limited, explaining why some recent attempts to locate the bird were unsuccessful. This limited population density also explains why one of the groups that followed our sighting had to search the entire day to spot the bird.

The habitat in this section is highly variable, changing rapidly sometimes within a kilometer. Moving through the area, one encounters a sequence of distinct ecological zones:

-

Sand Dunes: Open, shifting sands

-

Short Grass Fields: Stretching 1–2 kilometers

-

Planted Prosopis juliflora (Vilayati Babul): Approximately 1 km

-

Taller Prosopis cineraria (Khejri) mixed with Salvadora (Jaal) trees: The patch where our sighting occurred

The red arrows in the image below indicates the boundary that the Sind Woodpecker might not cross.

The red arrows indicate the potential limit of the Sind Woodpecker’s range in this section of the Indian boundary, in northwest Rajasthan. Photo by Harish Thangaraj.

Within the Khejri-Salvadora patch where our sighting occurred, we observed that the woodpeckers often bypassed Salvadora trees, showing a clear preference for Khejri. We could not confirm whether the species might also favor Vilayati Babul, as that planted patch was approximately 15 kms away and disconnected from this stand of trees where we observed the woodpeckers.

Habitat in western Rajasthan where Harish, Sudhir and Uras observed the Sind Woodpecker. The environment features a rapidly shifting landscape of sand dunes, short grass fields, and scattered Khejri and Jaal trees. Photo by Sudhir Paul.

This sighting validated our hypothesis that the Sind Woodpecker could be a regular bird in some parts of India. This specific area is an extremely narrow green belt along the border in western Rajasthan. Unfortunately, access to this location is restricted, and prior permission from BSF is required to visit this area. The estimated 2,500+ trees in this patch (based on a rough count) are crucial for the woodpecker’s survival, and any loss could displace the species from this area. That said, the Sind Woodpecker may well persist in other similar connected habitats along the northwestern border, provided those patches are accessible. Worthy exploration areas also exist to the west and northwest of Tanot and Longewala which was our second choice of site if we had failed to find the bird on day one. Google Earth reveals promising stretches of contiguous habitat with some degree of road connectivity, suggesting potential locations for future searches.

Possible areas for the Sind Woodpecker in northwest Rajasthan that are likely accessible by road. Image from Google Earth by Harish Thangaraj.

We managed to secure a sighting of the Sind Woodpecker, an achievement that adds to the photographic records for this elusive species.We hope this successful attempt of ours will encourage more bird enthusiasts to explore its habitat further and in general, create more interest among the Indian birding community to uncover more long-lost or even new rarities for India.

With a series of sightings across different seasons — in August 2011, October 2012, and February 2025 — we believe the Sind Woodpecker may be a resident species in this region, much like other Pied Woodpeckers in the Dendrocopos family. However, this hypothesis can only be confirmed if birders continue to look for this species in various seasons to determine whether it is present year-round.

Until we find the next rare bird!

About Harish and Sudhir

When Harish is not fulfilling his corporate responsibilities, he is out traveling to the different parts of the country to photograph his pending rare birds of India. He describes himself as a birder-photograher-twitcher combination who uses data analytics, research papers and credit card points effectively. He holds photos of almost 1200 Indian birds that he has phiotographed, on his mobile phone.

Photographing birds and climbing mountains are Sudhir’s favourite getaways from work. A dozen years ago, he was introduced to the world of birds while driving around a friend’s father to local birding hotspots. Fast forward to today, where finding our ornithological rarities has become a new passion for him.

Additional Media:

Left to Right: Harish Thangaraj, Sudhir Paul, and Uras Khan in search of the elusive woodpecker in the arid landscapes of northwestern Rajasthan.

Habitat where Sind Woodpecker was sighted. Video by Harish Thangaraj.

Male Sind Woodpecker in an arid habitat of western Rajasthan. Photo by Sudhir Paul.

Sudhir and Harish would like to thank Uras Khan for his help in the search for this bird. His matter-of-fact mention of the 2012 sighting to Sudhir is what piqued our interest in the quest for this woodpecker.

Banner Image: Desert landscape of Murar region in northwest Rajasthan. Photo by Harish Thangaraj.

Fantastically narrated……..

Congratulations to Harish and Sudhir on this rare find

I have seen and clicked Sind Woodpecker Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Delhi

Great work Harish and Sudir!!

Great narration. Thanks for sharing the details and the pictures. Kudos to all three of you.

Well I’m not into bird watching but this genuinely piqued my interest! Great article and even greater find

Wonderful attempt and the best thing is they were successful in first attempt! Congratulations for this achievement

Very nice narration!