By James Eaton

James Eaton is the co-founder of Birdtour Asia a reputed tour company in Asia. He is also the co-author of Lynx’s Field Guide–Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago. Since his first, transformative visit to India in 1999 (skipping college to make it happen!), with his friend Rob, James has evolved into a leading authority on Asian birds. He visits India every year and has birded in many states during his bird tours. Based in Malaysia for nearly 20 years, he’s birded and explored nearly all countries in Asia, leading to the discovery of new bird species and numerous rediscoveries. Here he talks about his adventures in exploring the habitats of a little-known Indian bird species.

In 2021, Bird Count India published a succulent article on Fantastic Birds and Where to Find Them. Fast forward two years, and where are we now? Well, for the majority of the 20 species listed, little has changed. With the exception of a handful of species, #20 on the list, Pale Rosefinch seems to be quite regular in Ladakh, and probably worthy of being taken off the list. #11, Hume’s Pheasant has turned out to be quite reliable (though the site already known), #10, Grey-bellied Wren Babbler, is actually likely an undescribed species. #8, Mount Victoria Babax is now quite straight forward to see in India (See blog). This list is primarily of national interest, with the exception of the Wren Babbler, which will be an exciting addition once formally described. Of international importance, Long-billed Bush Warbler on #13 is one species whose presence in India remains unchanged. But its rarity calls for those birders who seek excitement and glory. The carrot has indeed been dangled! This glimmer of hope was offered by the rediscovery in 2022 when I found two singing birds in Gilgit-Baltistan (a region administered by Pakistan). Fast forward to this year, three birds were found here, along with an additional record at Askole, which is just a mere 120km from the Line of Control (LoC) in Kashmir, 30km closer than my original 2022 sighting.

Historical status

From 1880’s to 1930’s many ornithologists including Biddulph (p.330), Davidson (p.15), Buchanan (p.131), Baker (p.362 )used statements like ‘very abundant’, ‘very common’, and ‘calling all day long’ to describe the status of Long-billed Bush Warbler (also known as Long-billed Grasshopper Warbler). At the Natural History Museum, Tring, UK (NHMUK), 56 specimens are stored in trays from this period, providing example of just how common the species must have been. There has been a paucity of verifiable records since, resulting in many misleading and inaccurate statements. Modern observations supported by documentation are almost entirely lacking and, in some cases, the evidence provided suggests a misidentification. For example, a photograph previously labelled as the species on the Oriental Bird Images website, taken in Himachal Pradesh in 2004, is not this species and, on account of its undertail-covert pattern and bright upperparts, is an Acrocephalus (Paul Leader in litt. 2022). Perhaps surprisingly, this error was not picked up by Kennerley & Pearson as their Reed and Bush Warblers handbook (p.171) have accepted the record. Looking back chronologically, records that do not specifically refer to a specimen or the species’ far-carrying song takes us back to the first half of the 20th century (See Fig 1).

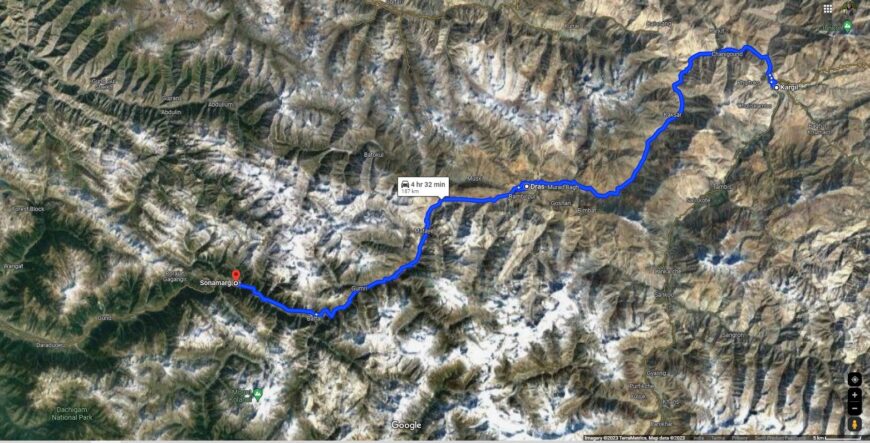

In Indian-administered Kashmir, this species was once well-known from the fertile valleys in the Kargil-Dras-Sonamarg area in Jammu & Kashmir (See Fig 2), an area stretching roughly 80 km. All the publications in the early 20th century are broadly consistent in describing it as locally common. Davidson wrote of the species: ‘Very abundant among the long grass arid weeds fringing the forests… We did not see it till the 8th June, when in the evening we heard its perpetual tic-tic- tic in the dusk. By the 10th it was very common and calling all day’. Similarly, Osmaston (p.989) found it to be ‘common’ in some areas of the Suru Valley, near the trading town of Kargil, even discovering more nests of this species than Lesser Whitethroat (Hume’s) Curruca curruca althaea, which remains a common breeder in the thickets there even today. Recent information is conspicuous by its near- absence. In 2015, Shashank Dalvi went in search of the species in the Suru Valley. He found two different individuals, both of which silently came into playback but showed themselves too briefly to obtain a photograph. This was the first time the species had been seen since a University of Southampton expedition in 1977, when a singing bird was photographed by Charles Williams, with an unseen second bird replying to it. The images were never published, nor picked up until my own research and becomes the first field photograph of the species. The bird was found singing in Sea Buckthorn Hippophae sp., and was even observed to use nearby trees, while the second bird remained in low scrub (Simon Delany in litt. 2022). A follow-up expedition in 1980 to the same area failed to produce any further sightings.

Fig 1: Long-billed Bush Warbler’s high-pitched, far-carrying song. Media by Andrew Spencer/ Macaulay Library

Fig 2: Valleys between Sonamarg and Kargil used to have the best known sites in the early 20th century. Map Source: Google

In the Pakistan administered regions, it was historically known from the Gilgit area, primarily the Naltar Valley (225 km northwest of the Sonamarg). This locality was first mentioned by Biddulph, who described it as common between 8,000–10,000 feet (=c.2,400–3,050 m) between June and August 1878.

T.J. Roberts mentions it to be present in June 1987 and in June 1996; four singing birds were found over two days (Dave Farrow in litt. 2022). Roberts also mentioned its preference for ‘the weed-grown embankments between terraced cultivation as well as sheltered glades with thickets of Ribes grossularia (wild gooseberry) on the edge of spruce forest, away from cultivation between 8,000 and 8,500 feet’ (about 2,400 and 2,500 m). Elsewhere in Pakistan, Baker mentioned that Whitehead found it to be ‘very common’ in parts of the Khagan Valley in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

In addition, a second subspecies, Locustella major innae is only known from specimens taken in the Kunlun Mountains of westernmost Xinjiang, China, in June 1874. There have been no field sightings since. Although perhaps a consequence of the lack of researchers and birders visiting this area, an extensive survey by Paul Leader and Geoff Carey in June–July 2003 failed to find it. This area is just north of the Line of Actual Control of the disputed Indian-China border in Ladakh. Is there any remaining habitat where birders go in search of Pale Rosefinch?

So what habitat is it currently known from? On the Pakistan-administered side, it is currently known from the edges of terraced cultivation (namely, potatoes) with a lush border of thickets and Rumex sp (docks) (See Fig 3.1 & 3.2), and while I did not personally record it in either wild gooseberry or Sea Buckthorn, it has since been discovered utilising the latter, at least. For those who have birded the valleys around Kargil, where I have, this habitat will sound familiar. The big difference, to my eyes, is the lack of lush vegetation dividing the terraced cultivation – this is the important difference and issue to search for and address. The area where I’ve found three singing birds is not a huge area; perhaps only about 2 hectares comprise an optimal habitat.

Fig 3.1: Habitat of Long-billed Bush Warbler. Photo by James Eaton

Fig 3.2: Habitat with Rumex sp bordering the field. Photo by James Eaton

Fig 4: Long-billed Bush Warbler perched on top of Rumex sp. Photo by James Eaton

Fig 5.1: Long-billed Bush Warbler perched on top of Sea buckthorn shrubs. Media by Andrew Spencer/ Macaulay Library

Fig 5.2: Singing Long-billed Bush Warbler in sea buckthorn scrub along the Naltar river. Media by Andrew Spencer/ Macaulay Library

Current status and threats

Long-billed Bush Warbler is currently classified as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List. BirdLife states that its range is ‘apparently contracting, possibly owing to changes in agricultural practices’, and that it is ‘poorly known and infrequently recorded, but this is at least in part due to its highly secretive behaviour and the current inaccessibility of its range’. This is in large part true; however, it is not secretive during the summer months, as various authors have stated, and even over 100 years ago, it was seemingly only mentioned repeatedly from four valleys (Suru, Sonamarg, Khagan, and Naltar). The account is correct, however, in asserting that the area has received little ornithological attention, with turbulent politics impacting the region since the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947.

These four valleys have, however, received some attention from ornithologists in recent years. In particular, Sonamarg has become a fairly popular birding location due to the increasing accessibility for birders (evidenced by the various eBird hotspots in the area, including Sonamarg itself). Heavy grazing has resulted in little habitat for Long-billed Bush Warbler, however, any birder that has spent time in Jammu and Kashmir will have noticed the severe grazing pressure on the landscape (and probably a reason why Orange Bullfinch has become so difficult in the breeding season!). Despite making repeated visits to the Sonamarg valley in the last ten years, I’ve yet to find any areas of extensive long grass or arid weeds with a lush undergrowth. What is mind-blowing is that there are even specimens obtained from Gulmarg, not only a popular ski resort but also a popular birding site, but with extreme levels of grazing now.

Indeed, the only records of the Indian-administered side from the past 80 years are the two from 1977 and 2015. As Kennerley & Pearson note, this may be due to habitat destruction caused by changing agricultural practices and overgrazing, with the same issues noted in the Kunlun mountains during a search for the form innae in Xinjiang, China.

Finding the bird in India

So, how does one find this bird in India? Well, the area where Shashank Dalvi found two birds is the same valley where Osmaston found it to be so common. I visited the following year with Shashank in late July, and though the habitat appeared suboptimal at the time, in hindsight, there were actually areas that could still hold the bird. My philosophy for finding birds has always been based on it being 80% preparation, 20% birding—the birding is the easy bit! Scouring Google Earth, there are a number of pockets of potential habitat. I strongly urge any Indian birder with a sense of adventure and the willingness and means to do so to check out these potential areas: The terraced fields between Sankoo and Stakpa (see Fig 6) though is it too high an elevation? It’s worth remembering that you don’t need to find areas well away from habitation; go to areas with the correct habitat, even in the field immediately around Saliskote village.

Or, perhaps trying a whole new area, driving well off the beaten track, making regular stops depending on the appearance of the surrounding habitat along the road between and around Shah Pora to Abdullum—if no Bush Warbler, it sure will be a fascinating journey!

Despite scouring Google Earth, the availability of habitat is preventing offering a whole range of localities, and no doubt the habitat will change subtly year-on-year due to grazing and pesticide pressures. Photo document all the habitat visited—this might seem of little use at the time, but can be useful in future research.

Remember, the time to visit is between mid-June (no earlier than 10th June to be sure) and mid-July. In any cultivated area with a nice border of Rumex and lush vegetation, try using a recording of the bird (available on Merlin, for example) for several minutes in the open habitat. Then listen and wait for five minutes, at least—do not rush off until you’ve given the bird plenty of time to reply. If there is no reply, then move on to the next area—like almost any Bush Warbler, if there are territorial birds in the area, they will sing back. Patience is a virtue. But so is covering as much area as possible. In the meantime, enjoy the plethora of other breeding birds in the area—Hume’s Whitethroats, Himalayan Rubythroats, Mountain Chiffchaffs, Common Rosefinches—and, if you are really lucky, perhaps Blyth’s Rosefinch too, which should also be found in the area despite being a low-density bird.

Fig 6: Terraced fields between Sankoo and Stakpa is a potential site. Map Source: Google Earth

This article has concentrated on Long-billed Bush Warbler’s breeding grounds. However, it also has to winter somewhere! West Himalayan Bush Warbler is a bird we can draw parallels from. Just five years ago, this bird was so little known in the winter months, yet now we know it has a broad wintering range and quite easy to see. It might be interesting to explore the marshlands below the foothills of the western Himalaya during the winter, but especially April-May when the birds are likely to be vocal. Perhaps anywhere that holds Rufous-vented Grass Babbler or Jerdon’s Babbler (Indus), in the Punjab (like Harike) to Jammu itself is worth a visit – give it a go!

Header Image: Long-billed Bush Warbler Locustella major by James Eaton