This is a guest post by Kaushik Sarkar, who is a nature enthusiast with great interest in avian ecology and interactions of birds with the modified environments and transitioning landscapes. He graduated with an MSc in Wildlife Biology and Conservation from NCBS Bangalore and is currently part of the Bird Count India team.

Amid a confined space, the mind looks for a place to escape or whatever resembles a window to the outside world!

This was the situation with most of us when the Covid-19 lockdown caught us off guard in March 2020. For me, it was a halt in my research work on owls, which after much struggle and obstacles was finally moving smoothly. I was fretting over the completion of my thesis, sitting in my field base in Joypur, a village adjacent to the Dehing Patkai National Park (then Wildlife Sanctuary). With all the things out of my hands, I gave in and went back to doing the thing I love the most—birding!

Since I was anyways birding, my guide (Ashwin Viswanathan) suggested that I do systematic birding and possibly document the migration of some species that pass through this part of northeast India. This idea interested me and I started my lockdown birding. I decided to make eight-15-minute checklists a day— four in the morning, four in the evening and upload them to eBird. Thus, for the next six weeks, this became my regular activity.

A huge peepal tree (Ficus religiosa) besides my field base became my partner in this endeavour!

The benefit of living in a village setting, especially in the northeast, is that there is always a possibility of encountering a variety of species, even from a rooftop. The fruiting peepal acted as a magnet to many species— three species of barbets, two species of bulbuls, Asian Koels, Yellow-footed Green-Pigeons, and Oriental Pied Hornbills. I was surprised by the number of species of mynas and starlings that visited the tree, including Common Myna, Jungle Myna, Great Myna, Common Hill Myna, Chestnut-tailed Starling, and Asian Pied Starling. The dawn chorus was sung by Black-hooded Orioles, Rufous Treepie, Cinereous Tit, Oriental Magpie Robin, and Tailorbirds while evenings would include an air show performed by Asian Palm Swifts and flocks of Rose-ringed and Red-breasted Parakeets.

Chestnut-tailed Starling on the Ficus tree

Despite being away from the forests and work, owls were still part of my life during the lockdown. I found, there were five species of owls around my terrace. March – April is part of the breeding season for owls hence they are very active at this time of the year. An Asian Barred Owlet would call regularly in the morning and evening. In April, the day it found a mate it stopped calling, which preceded with two days of territorial fights. A Brown Hawk-Owl pair used to call every night from the Ficus tree, but when the lockdown started, their call timings shifted from 8-9 pm to 6-7 pm. While the Oriental Scops Owl and the Collared Scops Owl would call intermittently, screeches of the Spotted Owlet in the dead of the night were exciting and I uploaded several incidental checklists.

Brown Hawk Owl calling from the Ficus tree

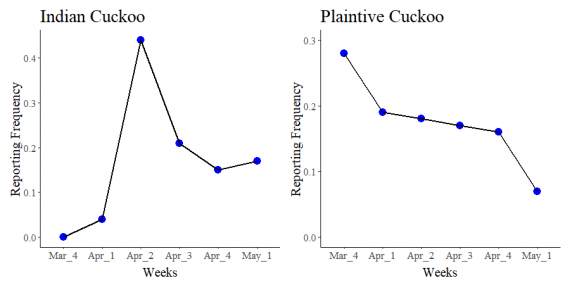

By mid-April, things were getting very interesting, because now apart from the regular ones, migratory birds started to show up. I was told to look out for cuckoos that will pass by. The Plaintive Cuckoo was already in the region in March. On 6th April I heard the first Indian Cuckoo of the season. There was a sudden spike in the numbers of the Indian Cuckoo following their first appearance in the season then the numbers stabilized in the following weeks. In contrast to this the number of Plaintive Cuckoos. reduced (See graph below).

Frequency graph of Indian and Plaintive Cuckoo in the checklists across the weeks.

On 20th April, the raptor with one of the longest migration routes flew over my terrace, the Amur Falcon. Five days later a Malayan Night Heron and a Pied Harrier also passed over. These unique sightings reminded me of how important part of migration this part of the world is.

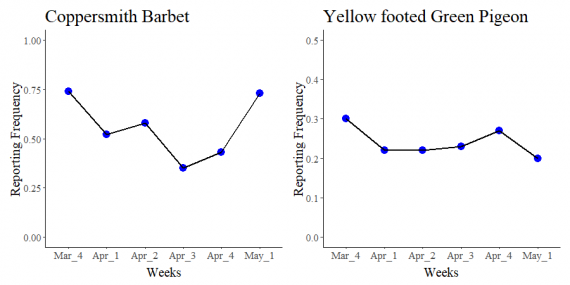

Within a couple of weeks of lockdown, some interesting forest birds were seen at my field base and in the village—Maroon Oriole, Orange-bellied Leafbird, Ashy-headed Green-Pigeon and Wedge-tailed Green-Pigeon. It made me wonder if the absence of intense human activities can allow many more species to utilize human-modified landscapes. Regular birding also gave me an opportunity of observing different natural history moments. In late April, birds were looking for nesting places. A Coppersmith Barbet inspected the existing tree cavities in the ficus for a nest but got chased away multiple times by a Lineated Barbet. A pair of Jungle Mynas successfully raised their chicks in one of the hollows in the Ficus tree. This ficus was fruiting when I began my daily lists. By the end of the first week of April, fruits finished on the tree but then again by the last week of April it started fruiting again. Visitation of certain birds reduced during that period when fruits were absent. One morning, I saw a Pied Falconet catch and eat a Chestnut-tailed Starling. A rainy evening marked the emergence of alates (flying termites) and the beginning of a feeding frenzy—bulbuls, mynas, and drongos were at their best in aerial acrobats to catch these alates. An Indochinese Roller also joined the party. Asian Palm Swifts and Blyth’s Swifts were flying so low that some zoomed past my ear for this buffet. The most surprising thing was a Blue-throated Barbet, a primary frugivore, sallying in the air to catch the alates which were very unlike it. Many more such interesting events happened throughout my period of lockdown birding.

Frequency graph of some birds that showed lower visitations when figs were absent

On 5th May, I was able to start work again but my streak of 43 days of intense checklist-making was broken. By the end of my stay in Joypur in June, I had made 321 checklists on eBird and recorded 92 species just from my terrace. These regular checklists gave me some amazing insights about how biodiverse our surroundings are, how bird abundances change with time and resources around, and when birds migrate. Our simple activity of just noting what we saw, when, and where we saw and adding it to a database like eBird can provide information that can be used by researchers, conservationists, or anyone who is excited about birds.

Despite being away from the forests and work, owls were still part of my life in lockdown. When I was not birding, I also used to paint, especially on pebbles. These hobbies became my solace and helped me overcome stress and boredom. Perhaps birding is also an escape for many who find themselves stuck in their busy schedules but irrespective of where we are, we can all enjoy and contribute to the understanding of birds.

Pebble art during the lockdown

Mottled Wood-Owl on a pebble

All the photographs and the header image (Collared Scops-Owl) in this article are by Kaushik Sarkar. More of Kaushik’s work can be seen here.

This is awesome experience. Thanks for sharing it.

Most appropriate to put it in salim ali’s way – practically no square of the Indian subcontinent is static for any length of time as regards it’s bird population, and there is an unending chain of comings and goings of species and individuals.

Wonderful observations kaushik. I can relate to your observations as many of these i have also observed here in Tezpur

Beautiful experience. This shows the value of perseverance. And motivation for others, like me.

A great post of observing Bird during Covid 19 lock down period.

awesome observation and even awesome pebble painting Sir