What can focused birdwatching reveal in a landscape few have looked at closely? In the northern Deccan, a small team set out to find out — charting birds, habitats, and stories hidden in plain sight.

Secrets of unexplored India: Revelations from birdwatching in the northern Deccan

By Samakshi Tiwari and Shubham Giri

Systematic bird surveys, though logistically demanding, are built on simple methods and have the power to reveal patterns and species that might otherwise remain hidden. These efforts are within the reach of universities, NGOs, and research institutions.

Despite its long history of birdwatching, India has huge potential for exciting discoveries and new learning. We often think of the Western Himalayas, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and Northeastern India as the ultimate frontiers for exploration in India, and not wrongly so! The recent sighting of the European Greenfinch from Srinagar is significant, as it lies far outside its main distribution range in Central Asia. We all remember the thrilling stories surrounding the discoveries of the Lisu Wren-Babbler from far eastern Arunachal Pradesh, and the Mount Victoria Babax from Mizoram. Such explorations not only lead to species-level discoveries but also contribute to a deeper understanding of bird communities not only in these regions but also across the country. Who knew, for instance, that the Buff-throated Warbler and Grey-sided Thrush were regular wintering birds alongside the Babax?

These areas are not the only under explored landscapes in the country! A huge part of Central India remains poorly explored, and past exploration has thrown up the most amazing learnings – the rediscovery of Forest Owlet not so long back, and discoveries of hidden populations of Indian Spotted Creeper, and most importantly, Green Avadavat! Perhaps the least explored part of Central India is the northern Deccan that should host thriving populations of our declining grassland specialists (Florican, Courser, Sandgrouse), populations of Green Avadavat and Spotted Creeper, and maybe even a lost subspecies of Painted Bush-Quail. But is this really the case?

Supported by The Habitats Trust, we set out on a year-long journey to explore and understand this landscape better. This is the story of what we found and have learnt halfway through this journey.

We’ve been conducting exploratory bird surveys across various districts in Maharashtra during both summer and winter seasons. Explore the trip reports below to see what we found.

Fig.1: Birding at the lesser explored Niwali Lake in Parbhani, which has formed as a backwater of a dam on the Karpara River.

What is the northern Deccan? It’s a vast fascinating landscape spreading through Maharashtra and Telangana that is flanked on two sides by the Western and Eastern Ghats. In the west, places like Beed are home to vast and beautiful grasslands, while the eastern parts, such as Gadchiroli, support stretches of deciduous forest. The perennial Godavari River forms the lifeline of the region, sustained by a network of rivers that often run dry in the summer months. Positioned at the centre of the distribution range for many Indian resident birds, some of which are habitat specialists, this stretch of the Deccan presents a unique opportunity to understand avian diversity across a mosaic of habitats.

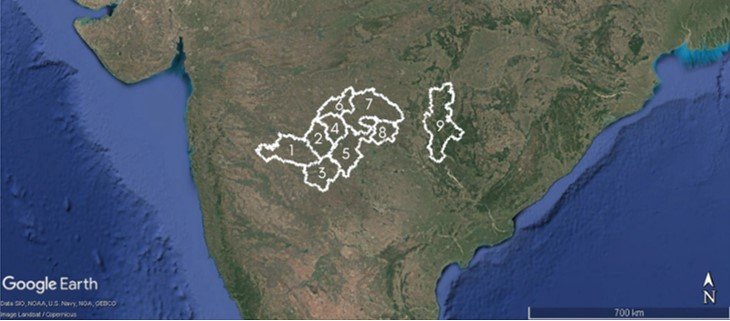

Fig. 2: Map showing the study area

We surveyed parts of Maharashtra and Telangana, along the borders of Chhattisgarh and Odisha, covering nine districts across the Vidarbha and Marathwada regions of Maharashtra.1. Beed, 2. Parbhani, 3. Latur, 4. Hingoli, 5. Nanded, 6. Washim, 7. Yavatmal, 8. Adilabad and 9. Gadchiroli.

Fig. 3: The beautiful vast grasslands of Beed (left) and deciduous forests of Gadchiroli (right).

Since then, we have compiled more than 800 bird checklists and recorded around 250 species. We have travelled over 20,000 kilometres and explored several habitats that were previously undocumented. These efforts have already revealed some of the quieter secrets of the northern Deccan. While our exploration continues, here are some important questions we have started to answer.

How are House Sparrows faring?

The House Sparrow is a beloved bird across India. Sadly, it has become increasingly difficult to spot in many cities, raising nationwide concerns for its well being. However, the State of India’s Birds (SoIB) 2020 assessment suggested that House Sparrows may still be doing well outside major urban centres. But does this trend hold true in the vast rural stretches of the northern Deccan — a landscape that remains largely unexplored and is yet to be fully represented in national assessments such as SoIB?

To better understand the status of this iconic species and other birds that thrive around people, we systematically surveyed villages across the region — something that birders don’t often do!

Fig. 4: A village we surveyed in Nanded (left) and A House Sparrow pair in Beed (right).

Good news, House Sparrow was thriving!

Out of the 75 species we recorded across 34 villages, House Sparrow was the second most frequently recorded species! And was present in 29 of the villages we surveyed. It was next only to Purple Sunbird. Other most common birds were Red-vented Bulbul, Laughing Dove, and Green Bee-eater. In contrast, another familiar urban bird, the Rock Pigeon, was recorded in only six villages.

It was heartening to see that people in this region continue to share their lives with such a diversity of birds, including a healthy number of House Sparrows. We hope that this coexistence continues.

How diverse are the vast grasslands of the Deccan?

Deccan has some of the most beautiful grasslands we have ever seen. But how are grassland species faring here? Many grassland specialists are in decline across the country, making it all the more important to understand how they are faring in regions that have never been surveyed intensively before. Could the northern Deccan be a refuge for some of these threatened species? To find out, we first had to find suitable habitats.

We used satellite imagery to identify 5 x 5 km grids that had lots of grassland. We then chose some of these grids for field surveys, walking two 250 m transects (travelling checklist) in each. Our work began in Adilabad, where grasslands were hard to find and broken up by croplands, and as expected, we found few grassland specialists.

Fig. 5: A trail we surveyed in winter in Yavatmal. The grasslands here were more extensive and less disturbed than those in Adilabad, but they still did not support specialist species.

But when we reached Beed, we found vast grasslands and thought we would hear and see several raptors, shrikes and sandgrouses. Yet, even here, we did not record species like Great Grey Shrike or any sandgrouse, and sightings of harriers were very few. We also didn’t record the rapidly declining Indian Courser during the winter, prompting questions about its conservation status, currently proposed for uplisting to Near Threatened.

Despite over 2000 minutes (33 hours) of field effort, we encountered very few grassland specialists — a sobering reminder of the mounting pressures these birds face, even in landscapes that look suitable.

Fig. 6: A trail across winter and summer in Beed. Despite the absence of most grassland specialists, it was exciting to explore these grasslands. They felt like entirely different worlds in the two seasons we visited.

What are the most common birds in the forests of the northern Deccan?

Before going ahead, take a few moments to make a guess.

What did you think — Jungle Myna, Jungle Prinia, or perhaps a sunbird?

Surprise! Plum-headed Parakeet was the most common in the winter, and Yellow-throated Sparrow in the summer. This was calculated from 256 checklists in 32 forested 5 x 5 km grids across nine districts and both seasons.

Fig. 7: A woodland in the northern Deccan in the winter (left). Plum-headed Parakeet from Yavatmal (right). We had to dig deep into our hard drives to find its photo from the field — it was so common that we didn’t pay enough attention to photograph it.

Fig. 8: In the summer, large portions of the forest had already experienced fire by March. Amidst the charred landscapes, one species stood out — Yellow-throated Sparrow (the second most common species after Spotted Dove in summer), which was singing prominently across many of these sites.

We also had a few exciting surprises, including an “out-of range” Malabar Whistling Thrush and Grey Junglefowl in Adilabad. You may be wondering if we found Indian Spotted Creeper or Forest Owlet in the region. Not yet! But we think the landscape has suitable habitats and we hope to find them in the future.

Do the Endangered Black-bellied Tern and the declining Little Tern breed in the northern Deccan?

Despite many rivers and wetlands, Black-bellied Tern had never been recorded in the region. Also, Little Tern had not been recorded from multiple districts.

In winter, River Tern was one of the most common birds at wetlands across this region.

Our summer surveys revealed that Little Tern was present in wetlands across six districts. In four of these (Parbhani, Hingoli, Jalna and Washim), we recorded it on eBird for the first time. The most exciting find related to wetlands came from the Wainganga River in Gadchiroli. After walking over an hour along the river’s banks in the scorching heart, we noticed adults of Black-bellied Tern flying and on a later visit saw juveniles too.

Fig. 9: Little Tern in Washim (left) and Black-bellied Tern in Gadchiroli (right).

Another rewarding visit was to the Bembla Wetland in Yavatmal, where we observed hundreds of Tufted Ducks, along with several other interesting sightings. In Latur, we also recorded flocks of Common Cranes and Demoiselle Cranes — a truly breathtaking sight.

A call for wider exploration

All of this was uncovered by a small team. Imagine what more we could learn if similar efforts were carried out across other overlooked regions of India. With a shared sense of purpose and collaboration, we can begin to unlock the secrets of India’s diverse landscapes. Let’s ensure that even the most remote and forgotten habitats are not left out of our conservation story.

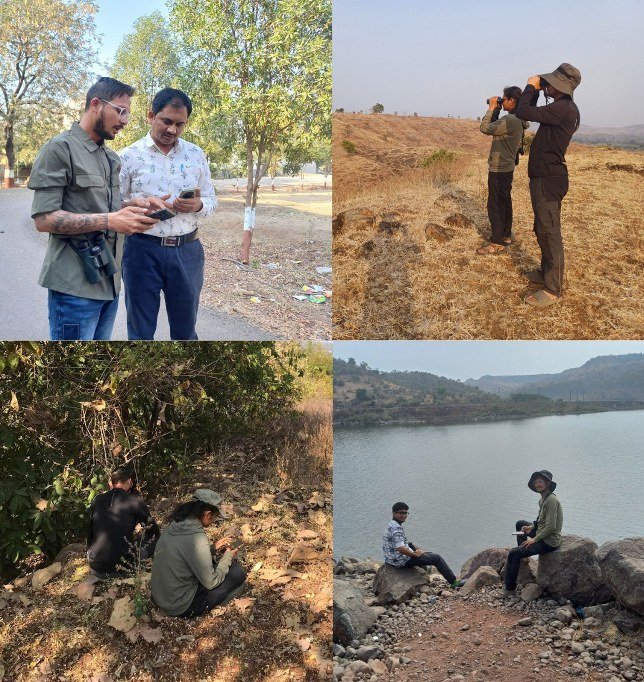

Fig. 10: Our field work across the northern deccan. Data collection (left) and exploration (right).

Credits & Acknowledgements

Fig. 1: Katakam Sheshank; Fig. 9 (right): Shubham Giri; Fig. 11 — Bottom left: Swati Kadu, Top right: Vinayak Dayal; All other images: Samakshi Tiwari.

We would like to thank the following people for their help in fieldwork, accommodation, workshop organisation, exploration and guidance:

Abhijit Lohiya, Abhijit Rasal, Amrut Bang, Anand Bhandari, Anil Uratwad, Anjali Kulmethe, Anuradha Puri, Anuradha Sanjay Herkar, Atindra Katti, Bandu Limbaji Nannaware, Chetan Bharti, Chetna Ugale, Deeti Triveni, Dhananjay Gutte, Dnyaneshwar Giram, Gandikota Mohan, Gaurav Adhikari, Harsha Vardhan, Hemant Ware, Jayant Wadatakar, Kalyaan Savant, Katakam Sheshank, Madhav Nagargoje, Madhukar Gaikwad, Mayatai Gaikwad, Manik Puri, Manoj Bind, Mayuri Bharti, M.D. Sarode, Milind Sawdekar, Milind Umare, Praveen Joshi, Raja Bandi, Sanjay Herkar, Sarika Sangekar, Shrikant S. Gawande, Shrushti Sonawane, Shubhda Lohiya, Siddharth Sonawane, Soham Pattekar, Solanke Ravi, Subhas J. Pare, Swati Kadu, Tak Shyam, Uppuleti Anil Kumar, Vijay Dhakane, Vikram Sarkar and Vinayak Dayal.

We also thank members of the Forest Departments of Telangana and Maharashtra, and the managements and teachers of Bahirji Smarak Mahavidyalaya – Basmatnagar, Hingoli; Dayanand Science College, Latur; Jivanrao Pare High School, Jalna; Rajarshi Shahu College, Latur; Yogeshwari Mahavidyalaya, Ambajogai, Beed; and the Kawal Bird Festival for helping us organise workshops.

eBird trip reports:

🟡 Summer Surveys

-

Adilabad, Yavatmal, Chandrapur, and Gadchiroli

View Trip Report » -

Nanded, Hingoli, Latur, Beed, Washim, Parbhani, and Jalna

View Trip Report »

🔵 Winter Surveys

-

Adilabad, Yavatmal, Chandrapur, and Gadchiroli

View Trip Report » -

Nanded, Hingoli, Latur, Beed, Washim, Parbhani, and Jalna

View Trip Report »

About the authors:

Samakshi is a bird researcher focused on documenting and understanding avian diversity across lesser-known landscapes in India. Currently working in the Deccan region with the Education and Public Engagement team at Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF), she is keen to collaborate with like-minded individuals to study birds systematically across the country and contribute to their conservation.

Shubham explores Maharashtra and surrounding regions to document bird diversity and promote birdwatching through collaboration. A lifelong animal rescuer, he has contributed to Forest Owlet research in Central India and now works with the Education and Public Engagement team at NCF.

Header Image: A Greylag Goose among Bar-headed Geese at Ekburji Dam during the winter months. Photo by Samakshi Tiwari / Macaulay Library

Kudos to the team

Thank you