This is a guest article by Pritam Baruah. Pritam has been birding around the world for over 18 years. He especially enjoys listening to the extraordinary songs of the resident Northern Mockingbird & Oriental Magpie-Robin at his homes in California & Assam.

This is a revised and expanded version of an article originally published in the inaugural issue of ‘The Wild Trail Journal’ (summer 2015). It is aimed at both beginning and experienced birders with an interest in North East India, one of the most biodiverse regions in the world. This revised version has newly expanded sections with additional information on bird-habitat ecology, more photos, and inline links for further exploration.

Cover image: Sub-tropical montane evergreen forest, Hayuliang, Arunachal Pradesh. © Saurabh Sawant

The Habitat Clue

From lowland rainforests to alpine tundra, from swamps to fast flowing rivers, from urban buildings to cultivation, birds are everywhere. But the truth is, no single species is found in all habitats. Most species typically occur in specific habitats, and understanding the habitat around you is key to knowing what to expect, and to finding and identifying species. For example, the Slender-billed Babbler is highly specialized to large stretches of undisturbed tall grass and it should not be looked for elsewhere. But the Jungle Babbler is somewhat of a generalist and it can be found in scrub, open forest or degraded grass. And there is no point looking for a Pygmy Wren-Babbler in any of these habitats, as it is confined to damp undergrowth in moist forest.

Habitat is described by vegetation and physical structure, say pine forest or dipterocarp dominated lowland rainforest, or simply a river with exposed rock and sand banks. Often the presence of certain plant communities is indicative of the presence of certain birds. For example, a flowering rhododendron patch will almost certainly hold sunbirds such as Mrs Gould’s, while dwarf bamboo might hold Blyth’s Tragopan. Just physical structure can be telling as well: Steep moist cliff sides with honey combs might reveal Yellow-rumped Honeyguide and Small Pratincole might be present in exposed sand bars along rivers.

The habitat clue might even allow differentiating between similar looking species. For example, if a non-comprehensive set of field marks on a tiny warbler seen in a garden points to either Yellow-browed Leaf Warbler or Mandelli’s Leaf Warbler, then it may be deduced that the bird is likely to be Yellow-browed rather than Mandelli’s because of the latter’s preference for relatively undisturbed broadleaved forest while the Yellow-browed prefers open woods.

For a birdwatcher, certain aspects of a bird are observable directly from the subject itself: shape, size, plumage, colour, behaviour, and vocalization. On the other hand, an understanding of habitat, range, elevation and time of the year – all closely related ecological parameters, are also essential for birdwatching. In the following sections we take a closer look at these.

Range, Elevation & Seasonality

To understand what a bird calls home, in addition to habitat it is essential to grasp the closely related concepts of range (distribution), elevation and their dependence on time of year (seasonality).

The range of a species is simply the area where the species is known to be found. That species would be expected to be found in suitable habitat across its range. Range is described by boundaries that are based on major geographical features. For example, while the Brown-capped Laughingthrush ranges over the Patkai and Barail Hills, the Marsh Babbler is confined to the Brahmaputra valley. Additionally, political boundaries may be used as qualifiers for range. Such as, Rufous-throated Wren-Babbler is distributed across the Eastern Himalayas of India (Arunachal Pradesh & Sikkim) and Bhutan.

Migratory species obviously have different ranges in different seasons (disjoint ranges). Hence, the ranges of migrants are also considered to be seasonal. These disjoint ranges are very far apart for long distance migrants such as the Bar-headed Goose. Large numbers of Bar-headed Geese fly to spend winters in the Brahmaputra valley lowlands, which is part of the species’ winter range. On the other hand, they breed during the summer in Mongolia, which is part of the species’ summer or breeding range. Furthermore, birds are considered to be passage migrants in locations where they briefly stop for rest and feed along flyways that connect their winter and summer ranges. The spectacular gathering of Amur Falcons in Pangti, Nagaland, where they feed on insects on their way to Africa is an example of passage on a massive scale.

Disjoint ranges are not very far apart for altitudinal migrants or those that show local movements. They might even overlap. For example, the Snowy-browed Flycatcher breeds anywhere between 1500 masl to 3000 masl in elevation. But in winter most of the population moves much lower down to the foothills and plains. However it is found up to 2000 masl even in winter so there is an overlapping elevation band of 500 meters between its summer and winter ranges. Compare with Fire-tailed Sunbird or Golden Bush Robin which are also altitudinal migrants but there is little to no overlap in its summer and winter ranges (they both breed in high alpine shrubs but winter lower in broadleaf forest; Fire-tailed Sunbird mostly in open forest and Golden Bush Robin in grass and thickets).

While seasonal changes in elevation are pronounced for certain migrant species, some other hill species are prone to only minor local movements. These are found in fixed elevation bands throughout the year but population densities are variable across this band over time; higher density in the lower parts of the band in winter and higher density in the upper parts of the band in summer. For example, Rufous-throated Hill Partridge and Striated Yuhina are less common in the lower parts of their elevation bands in summer during breeding. However, at any time of the year, both species are highly unlikely to be found in the plains or higher up in temperate forest.

Some movements are facultative, in that, they occur in response to circumstances such as cold snaps, depletion of food, fruiting and flowering cycles or even habitat continuity across a wide elevation range. For example, Gould’s Sunbird can be found in the lowlands, even close to the Brahmaputra River, in February and March when certain trees are flowering. And Solitary Snipe might follow continuous fast flowing rivers all the way from the high mountains to the lowlands during the non-breeding season, presumably to take advantage of certain food sources. The exact reasons behind most facultative movements in the region are unknown, for example it is unclear why Striated Laughingthrush would join a mixed feeding flock in the lowlands of Digboi when they are restricted to mostly above 1000 masl across the region.

There may be some degree of variation in elevation bands across the entire range of a species. This is apparent in ranges of hill birds found both north and south of the Brahmaputra. In general, birds of the same species may range lower south of Brahmaputra than in the north. Also, the low ends of the elevation ranges of many hill birds are believed to be especially low in the eastern extremity of the Brahmaputra valley. This means that some species that are likely to be found here in winter are unlikely to be found in similar elevations further west. The Chestnut-headed Tesia and Eyebrowed Wren-Babbler are known to be found much lower in the south east of the Brahmaputra valley (down to undulating terrain in plains) than anywhere else.

The ranges of non-migratory species can be disjointed too and these ranges can be very far apart. The Great Hornbill for instance is resident disjointedly in North East India and the Western Ghats – a gap of at least 2000 km. Habitat preference remains the same across its entire range though. This might also occur due to human induced fragmentation of habitat – some obligate grassland species like Black-breasted Parrotbill are restricted to pockets of far flung grasslands with no hope of dispersal among these sites. Such fragmentation can be natural too, for example the grasslands in the low-lying Manipur Valley (800 masl) holds some of the same species as similar habitat lower down in Assam but these are separated by the Barail & Lushai Hills with no apparent continuity of habitat.

It should be noted that both migrants and non-migrants may use different habitats at different times of the year or even during the day. This is because the same habitat type might not satisfy all life activities such as breeding, displaying, feeding, and roosting and so on. For example the Gould’s Shortwing breeds above the timberline in rock-strewn areas but winters lower down in temperate forest of oak, fir and juniper usually in rocky gullies or tree falls. And the White-cheeked Partridge primarily spends most of its time foraging on the forest floor but it roosts at night on tree branches.

Birds of certain genera may be partial to specific plant genera that are widespread over different elevations. In such cases different species of the same genus might occur in different elevations while still associating with plants of the same family. This is apparent in the association of Pomatorhinus Scimitar-Babblers with bamboo across different elevations; White-browed is found in lower elevations, Red-billed in middle elevations and Streak-breasted in higher elevations along the same slope.

Scimitar-Babblers, anticlockwise from top left: White-browed – © Rofikul Islam; Red-billed & Streak-breasted © Nobajyoti Borgohain

Major areas

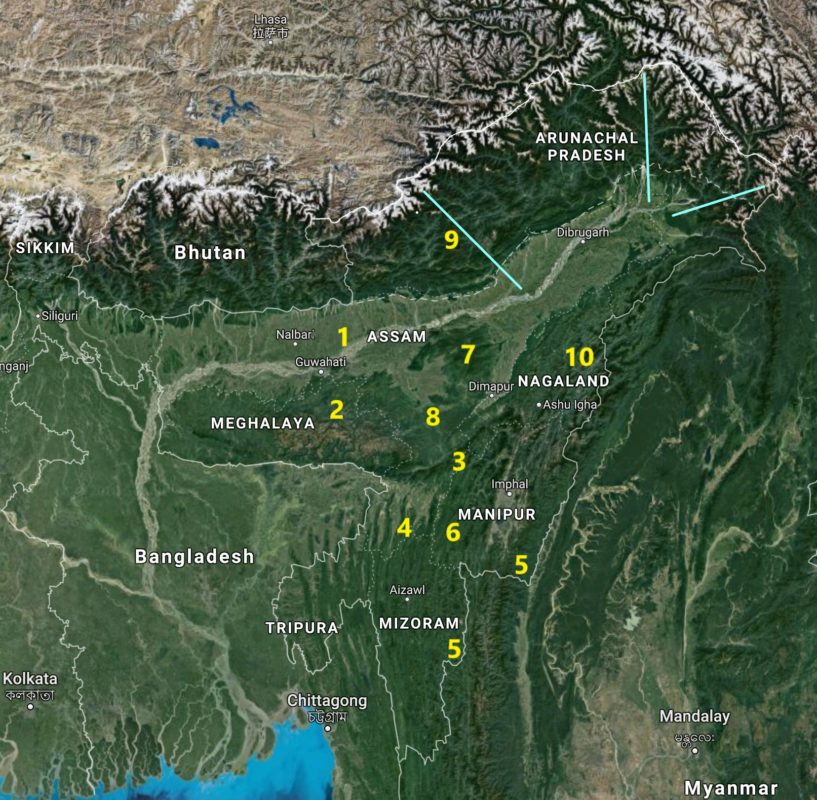

Map data © 2018 Google, annotations by Pritam Baruah

| 1 | Brahmaputra lowlands | 100 masl up to 600 masl in the foothills. Grasslands, wetlands, riverine & deciduous forests, semi-evergreen forests close to hills & evergreen forests close to hills in Upper Assam & SE Arunachal Pradesh. |

| 2 | Khasi Hills & Plateau | North slopes: mixed deciduous & semi-evergreen forests. South slopes: semi-evergreen & evergreen forests. Plateau: Subtropical pine. |

| 3 | Barail Range | Semi-evergreen & evergreen montane forest. |

| 4 | Cachar lowlands | Semi-evergreen & evergreen lowland forest. |

| 5 | Chin Hills | Semi-evergreen & evergreen montane forest. |

| 6 | Lushai Hills | Semi-evergreen & evergreen montane forest. |

| 7 | Karbi Hills | Semi-evergreen & deciduous forest. |

| 8 | Karbi – Dima Hasao lowlands | Dry deciduous forest. |

| 9 | Eastern Himalayan transects | From lowlands to over 6000 meters north of the Brahmaputra and about 3000 masl south of the river. Mixed semi-evergreen & evergreen forest in the foothills, subtropical evergreen above it, followed by temperate cloud forests, sub-alpine forest, tundra above the tree line. |

| 10 | Naga Hills | Semi-evergreen & evergreen montane forest. |

Habitat Types

North East India lies at the junction of the Eastern Himalayas biodiversity hotspot and the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot. It is home to a wide variety of habitats and elevation zones and as such, holds the highest diversity of birds in the entire oriental region. In this, if one were to draw a straight line transect anywhere in the region from the lowlands to the highest ridges, it would yield well over 800 bird species, which is comparable to the best transects in the world. Below are summaries of the broad habitat types of the region and associated bird species:

Savannah and Grassland

Lowland wet Savannah, Orang NP. © Bikash Kalita

-

Lowland wet savannah

Consisting of both tall and short grass, this is the most threatened habitat of North East India and it is mostly confined to the Brahmaputra valley of Assam. Once extensive, most of it has already been diverted for agriculture and today, less than 1200 sq km of good quality grassland remains, all of it in isolated pockets. Only four major grassland areas make up most of what is remaining.

| Kaziranga | 400 sq km |

| Jamjing – Dibru Saikhowa – Kobo – Amarpur – D’Ering | 350 sq km |

| Manas | 250 sq km |

| Orang – Burachapori – Laokhowa | 120 sq km |

Many obligate lowland grassland species are now at a risk of extinction as a result of destruction of their grassland home. There has been no confirmed sighting of Manipur Bush Quail for 90 years and it is presumed extinct until someone comes up with a photo or a sound recording. The following list of north-east Indian grassland rarities are highly sought after by birdwatchers: Bengal Florican, Swamp Francolin, Black-breasted Parrotbill, Marsh Babbler, Slender-billed Babbler, Jerdon’s Babbler, Swamp Prinia, Rufous-rumped Grassbird, Bristled Grassbird, Jerdon’s Bushchat, Finn’s Weaver.

Bengal Florican, Manas National Park © Roon Bhuyan

-

Montane grassland & scrub

These are middle elevation grasslands and scrub that have generated in areas of major landslides or in areas of abandoned shifting agriculture (jhum). If these grasslands are not suitable for agriculture then they may remain pristine for long periods (unless disrupted again by landslides or natural burns). Manipur Bush Quail of the nominate form P. m. manipurensis might still occur in this habitat. This form of grassland is common in Nagaland, Manipur, and Lohit Valley of Arunachal Pradesh and in the Dima Hasao district of Assam. Spot-breasted Parrotbill and Brownish-flanked Bush Warbler are fairly common in this habitat in suitable elevations. Similarly the much wanted near-endemic Yellow-throated Laughingthrush might make an appearance in grassy scrub. High elevation grass is covered in a subsequent section (see “Alpine Tundra”).

- Spot-breasted Parrotbill, Lohit Valley © Udayan Borthakur

- Montane grassland in Dima Hasao, Assam © Pritam Baruah

Wetlands

Wetlands (known as ‘Beel’ is Assam) are poorly drained low lying areas with open bodies of water often with floating aquatic vegetation, sand islands and marshes with emergent vegetation such as reeds. They may contain mixed grass that harbour typical grassland birds. Storks, egrets, lapwings and migrant waders may use marshes and edges of water, and open waters may contain large gatherings of waterfowl. Wetlands are also excellent habitats for finding plenty of open-country raptors.

Kathpora Beel, Kaziranga NP © Bikash Kalita

All major wetlands in North East India are located in the plains of Assam with the exception of Loktak Lake in the Manipur Valley. Furthermore, most wetlands are outside protected areas and they are threatened by silting (from both man-made and natural causes), reclamation, pollution, unplanned grass cutting and over-fishing. Even so, they remain highly productive environments, usually host to vast numbers of birds. It is very easy to find over 100 bird species in a day in any major wetland in the floodplains. Maguri-Motapung Beel near Dibru-Saikhowa NP, Sohola Beel in Kaziranga NP, Deepor Beel & Tamuliduba Beel (Pobitora WLS) in Guwahati and Loktak Lake in Manipur are the most productive wetlands that are easily accessible for birdwatching in North East India.

There are natural wetlands in the mountains as well (say high elevation lakes from glacial melt in Arunachal Pradesh) but these are not as productive as the wetlands in the floodplains. However, they serve as important staging grounds for passage migrants and also as breeding habitats for some species. Certain species like Solitary Snipe and Black-necked Crane are restricted to high elevation wetlands throughout the year.

Rivers & Streams

-

Fast flowing rivers & streams with exposed stone beds

Fast flowing rivers with exposed stone beds are found in the hills and in the edges of plains and hills. In the hills these rivers or streams flow especially rapidly because of steep terrain, and in sub-tropical elevations their edges usually have dense low lying vegetation followed by lush forest beyond. Forktails (Little, White-crowned, Spotted, Slaty-backed) and redstarts may be found on the exposed stones and silt patches, while wren-babblers may be found in ground hugging vegetation. At higher elevations, Brown and White-throated Dippers are characteristic species of this habitat. Marshy areas on the sides of these rivers might hold Long-billed Plover.

In the edges of hills and plains, these rivers broaden substantially and that exposes more suitable habitat like silt deposits, stones and near-shore plant communities. Fish and aquatic invertebrates become more abundant and that leads to proliferation of characteristic species such as forktails (Black-backed and White-crowned), redstarts, kingfishers, storks, cormorants, stone-curlews, pratincoles, and mergansers. Some highly sought after species like the Blyth’s Kingfisher, White-bellied Heron and Ibisbill can be found in this habitat during winter. The Noa-Dihing in Namdapha National Park, the Jia-Bhoroli in Pakhui-Nameri Tiger Reserve and Manas-Beki in Manas National Park are excellent examples of this habitat that are easily accessible.

White-bellied Heron, Namdapha NP © Deborshee Gogoi

-

Large rivers with sand banks & sand islands.

The mighty Brahmaputra, its major & minor tributaries and the Barak are the main examples of this habitat in the region. The Brahmaputra has one of the highest water and silt carrying capacities among all rivers in the world. Vast areas of sand deposits lie along this river system giving rise to habitats such as shallow pools, grasslands, riparian woods and wetlands. The open water and edges themselves support an incredible array of avian life: ducks, waders, geese, storks, kingfishers, bee-eaters, swallows, wagtails, pipits and cormorants are abundant along its braided course. Its sand islands (‘chapori’) are staging areas for migrants such as Common Crane and geese. And islands with good grass are very important areas for grassland birds. Sandy river banks also provide nesting habitat such as burrows for some species (such as Grey-throated Sand Martin). Raptors are especially well represented here and soaring individuals can be commonly seen during the day. Raptors such as Osprey & Pallas’ Fish Eagle are more common where riparian woodland skirts the rivers, as they enable convenient perches for roosting and feeding on prey but terrestrial raptors such as harriers and the Steppe Eagle can be found in treeless areas as well.

Braided Lohit river. © Saurabh Sawant

Forests

Forests are habitats dominated by trees and undergrowth. Forests are the most complex terrestrial habitats and as such, hold the highest diversity of avian life. Birdwatchers often consider this the most exciting habitat for the thrills of locating birds by spotting subtle movements amidst vegetation, deciphering the rich sound scape and most importantly the vast number of highly sought after species which have evolved from biological specializations possible only here. Forests may be qualified as primary (old growth, undisturbed, pristine) or secondary (forests that have naturally regrown after disturbance or are in a constant state of disruption). Owing to high variation in terrain, elevation, availability of water and soil types in North East India, there are several different forest types across the region. The major types are summarized below:

-

Moist and dry deciduous forest

In North East India found only in the plains and low foothills (up to 300 masl), deciduous forest is a type of hardwood forest that is dominated by trees that need to grow new leaves every year. These are mostly broadleaved trees such as Teak and Sal. The undergrowth is an evergreen or semi-evergreen layer consisting of bamboo and shrubs. The moist deciduous type is most prevalent in the ‘Duar’ region of lower Assam (plains at the southern edge of the Eastern Himalayas). Dry deciduous forests are found in the rain shadow areas of south Karbi Anglong and northern Dima Hasao and mixed deciduous forests are found along the northern edge of the Khasi Hills. The moist and mixed types are very rich in bird diversity but density of occurrence is lower than in semi-evergreen and evergreen forest and species dependent on factors related to wet conditions might be missing or relatively uncommon (eg: Lesser Shortwing). On the other hand, species preferring drier conditions might be more common than in the wetter forest types (eg: White-rumped Shama).

-

Lowland riverine forest

Riverine or riparian forest are secondary woodlands that occur in strips along broad waterways in the plains. These can be evergreen, semi-evergreen or deciduous depending on the soil type and overall climate. Strips prone to high degree of disruption are usually deciduous with an understory of grass and scrub. These can be seen along fast flowing rivers that are prone to changing course. Riparian semi-evergreen forests are common in the NE and the best areas can be found in Kaziranga National Park. There are also good tracts of riverine forests where the Lohit and Dibang rivers debauch into the plains. These strips are rich both in bird diversity and density. And since they are conducive to attracting woodland migrants over otherwise unsuitable habitat, they can be effective vagrant traps and stops in passage migration. These forests also provide roosting habitat for birds that forage in open habitat but prefer the relative protection of a forest edge for roosting (eg: Spot-winged Starling).

-

Seasonally flooded riverine forests & Salix swamps

This is a rare sub-type that is mostly found in the Dibru-Saikhowa NP of Upper Assam. Dominated by Salix trees, these forests are swampy and seasonally flooded. Presumably this used to be suitable habitat for White-winged Duck and even Masked Finfoot but these pockets have been disrupted by years of flooding, earthquakes and erosion, affecting both species. The Masked Finfoot is believed to be locally extinct and the White-winged Duck has also become very rare.

-

Tropical lowland semi-evergreen & evergreen forest

Lowlands are considered to be the elevation zone or life zone below 600 masl, consisting of plains and foothills. Tropical semi-evergreen and evergreen forests are the richest forest types in North East India in terms of faunal diversity. This leads to abundant food and ecological niches and hence they are very rich in birds too, especially in winter, when elevational and facultative migrants make their way down here after breeding in the mountains.

Semi-evergreen forests have both evergreen and deciduous plants. They mostly grow on rich alluvial soils and most of it has been converted to agriculture. But substantial stretches of semi-evergreen forest still exists all over the Brahmaputra valley including Manas NP, Nameri NP, Kaziranga NP (especially along the northern edge of Karbi Hills) and in the Barak valley, the vast foothills of Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Tripura and the north slope of the Khasi Hills. They usually have a dense understory of evergreen shrubs, low trees and bamboo.

Tropical lowland mixed forest, Pakke WLS © Pritam Baruah

Lowland evergreen forests are usually wetter and more likely to be primary (structured into well-defined tiers). Tall, straight, buttressed trees with broad cauliflower like crowns in the top canopy and emergent layers are a prominent feature of these forests. Large stretches of this forest type exists all along the low foothills of Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram and Tripura. Also remnant patches in southern Cachar and Upper Assam. The lowlands of Namdapha NP, Kamlang WLS (both Arunachal Pradesh) and Dehing-Patkai WLS (Upper Assam) are perhaps the best areas for birdwatching in this habitat.

In NE India both evergreen and semi-evergreen lowland forest types share the same species but certain species are likely to be found mostly in primary habitat and others may be mostly found in secondary or open habitat. For example, most lowland laughingthrushes are only found in secondary habitat and open forest. These forests abound in micro-habitats and to optimize resources, different species of birds organize themselves into different micro-habitats. For example, minivets mostly use the upper layers while Sultan Tit and most Phylloscopus warblers may use the middle layers. Wren-Babblers are invariably found in dense low undergrowth while most flycatchers prefer to stay just above that. Some species such as White-cheeked Partridge and Blue-naped Pitta are mostly restricted to the forest floor. Others like the Pale-headed Woodpecker, Pale-chinned Flycatcher and Rufous-headed Parrotbill are partial to bamboo while hornbills and pigeons prefer to shuttle between large fruiting trees like figs. White-winged Duck and Ruddy Kingfisher are dependent on forest pools while swampy areas around these pools attract understorey insectivores like flycatchers, warblers and shortwings.

- White-winged Duck, Nameri NP © Pritam Baruah

- Pale-chinned Flycatcher, Borajan RF © Amar Jyoti Saikia

-

Sub-tropical montane evergreen forest

This is the forest type that covers the largest area in North East India and it is found in all seven states with Arunachal Pradesh holding the bulk of it. The Eastern Himalayan forests in Arunachal Pradesh are considered to hold the second richest floral diversity among all montane forests in the world (after the Andes). Across the region these are mostly wet broadleaf forests rich in bamboo but there are also pockets of distinctive pine forests in eastern Arunachal Pradesh and in Khasi, Naga and Manipur Hills.

Rufous-necked Hornbill in sub-tropical evergreen forest, 1200 masl, Sessni, Eaglenest WLS © Pritam Baruah

From a birdwatcher’s point of view, this is the type where most of the ‘signature’ hill species of North East India are found. This life zone approximately ranges from the high limit of lowlands (600 masl) up to 1800 masl, having a wide vertical span of over 1200 meters across the region but more than 1500 meters locally. There is a profusion of microhabitats in this zone and different species have specialized to different elevation bands and microhabitats. For example, one of the most sought after birds of the region, the Beautiful Nuthatch, mostly occurs between 1100 masl to 1500 masl in winter. However its elevation range expands upwards in summer to temperate broadleaf forest (recorded in 2000 masl in summer) and expands downwards in winter (recorded in 800 masl). Other birds migrate to lowland elevations in winter (plains up to foothills less than 600 masl) but breed exclusively in this zone. An example of this is the Small Niltava which is common in the plains in winter but breeds between 1000-1800 masl. Others like the Hodgson’s Frogmouth range from lowlands all the way to the high limits of this zone (300 – 1800 masl) preferring bamboo that is common across both zones (but in the higher parts of Khasi Hills it has been recorded in sub-tropical pine forest too). The Rufous-necked Hornbill is another bird that is mostly restricted from the low foothills up to the middle areas of this zone, its movements depending on the availability of fruiting trees. Like many other species, although it primarily associates with evergreen forest, it may be found in other forest types in the lowlands.

Evergreen forest near Khonoma, Nagaland © Saurabh Sawant

Sub-tropical coniferous forest, 1200 masl, Lohit Valley © Pritam Baruah

-

Montane temperate forest (Cloud Forest)

The temperate forest zone in the Eastern Himalayas approximately range from 1800 masl to 3000 masl (locally higher). It is a complex zone with very high rainfall and vegetation ranging from broadleaf trees such as oak and rhododendron to coniferous forest (mostly pine, fir and juniper). Bamboo occurs all over the zone but there are exclusive bamboo dominated zones as well, primarily dwarf bamboo fields (such as in Dzukou, Nagaland). Oak forests may range lower in the hills south of the Brahmaputra. For instance the ridge lines in the Barail Range above 1600 masl are dominated by evergreen oaks. Across the region, locally there are areas of mixed conifers, rhododendron, oak and bamboo (usually in a narrow band from 2500 masl to 3000 masl). Certain conifer preferring species such as Rufous-naped Tit that are more common in the Himalayan pine forests west of central Bhutan might be found locally in these patches much further into the Eastern Himalayas (such as Mishmi Hills).

The lower limit of this zone is often the lower limit of occurrence of some iconic Eastern Himalayan species such as Blyth’s Tragopan and Sclater’s Monal. These forests are often covered by low-level clouds and this heavy moisture leads to an abundance of epiphytes all over the trees and the forest floor. Mature forests in this zone are often richly draped in mosses, lichens and ferns, leading birdwatchers to imagine the presence of the iconic Ward’s Trogon. Many other enigmatic species such as the Purple Cochoa and Mishmi Wren-Babbler breed within primary forest in this zone while Bugun Liocichla breeds in disturbed shrub filled ravines.

Cloud forest, Mishmi Hills © Bikash Kalita

Tragopanda Trail, Eaglenest WLS, Arunachal Pradesh. © Saurabh Sawant

-

Sub-alpine forest

These are forests dominated by rhododendrons, bamboo, birch, fir and junipers. The understory is very dense with scrub. This type is found from the high limits of temperate forests to the tree line which is at over 4000 meters in the Eastern Himalayas. Bar-winged Wren-Babbler, Brown-throated Fulvetta, Spotted Laughingthrush and various rosefinch are all species that are specialized to this elevation and habitat zone. Also, some species that winter lower, breed higher up in the sub-alpine zone (eg: Grey-backed Shrike, Fire-tailed Sunbird).

Alpine tundra

This is the zone above the tree line. It is mostly covered with low flowering plants, moss and short grass in the lower parts adjoining sub-alpine habitat. However, rock and scree with sparse cushion vegetation dominates the look and feel of this zone. Blood Pheasant and Himalayan Monal are iconic species of the alpine tundra (however they can be found slightly lower in neighbouring sub-alpine habitat too). The Snow Partridge may remain in rocky and grassy areas exclusively above the tree line while some like the dazzling Grandala prefer exposed rock beds and scree. Some species that winter in lower elevations from temperate woods to the plains, breed above the tree line. For example, the Rosy Pipit winters in the lowlands and the Gould’s Shortwing winters in temperate forests but both breed in tundra.

- Grandala, Sela Pass © Arka Sarkar

- Gould’s Shortwing, Sela Pass © Jainy Maria

Alpine tundra & lake, Sela Pass © Pritam Baruah

Human modified habitats

These are habitations and cultivations, not the most intuitive of bird habitats but still a type that is very important for many species of birds, as much as 10% of all birds found in the north east. Urban and rural settlements provide niche habitats like houses, gardens, garbage dumps and abandoned areas that function like pockets of wilderness. Ubiquitous species like House Sparrow, Common Crow, Common Myna and Rock Pigeon are exclusively dependent on these habitats. Gardens and slightly wild pockets are almost certain to hold Blue-throated Barbet, Red-vented Bulbul, Purple Sunbird, Common Tailorbird and Magpie-Robin among other species. Barn Owls may be found in unused ledges in apartment buildings while Blue Rock Thrush is often seen on suburban rooftops.

A common feature of the Brahmaputra plains are small ‘semi-natural’ woodlots maintained by villages, consisting of minor plantations for sustenance mixed with natural vegetation. To onlookers at a distance, these backyard woodlots seem to combine across the horizon, making the wide valley appear lush green. They hold important populations of migrant passerines in the winter, especially common flycatchers and warblers. Baya Weaver and Coppersmith Barbet are common in this habitat.

Some critically endangered species also depend on human modified habitats. For example the Greater Adjutant is almost entirely restricted to feeding from garbage dumps and breeding on protected trees in or near human settlements. With almost complete diversion of the short grass habitat preferred by Bengal Florican, a significant portion of its population now mostly survives in paddies (evidence of feasible populations in Sadiya and seed farm in Manas NP). Wintering populations of the critically endangered Yellow-breasted Bunting forage on harvested paddy fields. Furthermore, wet paddy fields are important habitats for waders, crakes, bitterns, raptors, kingfishers, buntings and munias.

Orchards and tea plantations form habitats for many species too. Orchards are important feeding and roosting areas for various parakeets, Black-hooded Oriole and Rufous Treepie. Tea plantations usually have open tree cover and some have steep unused valleys covered by lush vegetation, particularly bamboo. If such tea plantations are near forested hills, they can harbor a tremendous variety of species. The Diring Tea Estate just south of Kaziranga NP is an outstanding example of forest birds adjusting in man-made ‘forest-like’ habitats; Blue-naped Pitta, White-browed Scimitar Babbler, Lesser & Greater Necklaced Laughingthrush, Barred Buttonquail, Painted Snipe, Black-tailed Crake, Pied Falconet, Brown Fish Owl, Siberian Rubythroat, Mountain Tailorbird and a large assortment of warblers & woodpeckers are just some of the possibilities.

‘Forest-like’ Diring Tea Estate © Bikash Kalita

Conclusion

The above section provided a summary of the broad habitat types and their associations with different species of birds. However, it does not delve into complexities of habitat selection (why a certain species chooses one habitat type over another), the nature of boundaries between adjacent habitats, habitat change over time and changing distributions of birds over time. Overall, this article was intended to be an introduction to the relationship between birds, habitat, range, elevation and seasonality, hoping to aid birdwatchers and bird photographers better understand the environment around them. This understanding is important in that, not only will it enrich their field experience but it may also develop an appreciation for conservation of habitats. Habitat destruction is the single most important reason today for the decline of bird populations. For example, it should be pretty clear from this article that if the bamboo understorey is extracted from an area of forest then although that area remains a forest if seen from above, it is no longer the same habitat it used to be and the biodiversity within it is bound to plummet. Today over ninety percent of the region’s natural grasslands have disappeared and widespread shifting cultivation has destroyed the original structure of hill forests in vast areas. This has resulted in lowered biodiversity and has even driven some species to near extinction. Thus it should be clear that the key to watching birds is to understand habitat and the key to protecting birds is to protect habitat.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses special thanks to Amar Jyoti Saikia, Arka Sarkar, Bikash Kalita, Deborshee Gogoi, Nobajyoti Borgohain, Jainy Maria, Rofikul Islam, Roon Bhuyan, Saurabh Sawant and Udayan Borthakur for generously contributing their photos to supplement this article.

© Pritam Baruah, 2018

Hello,

Baruah Sir. can I have a pdf file of the same.

Hello Manas, the admins are working on a way to generate a print/reader friendly output which can be accurately converted to PDF. I suppose that will take a bit of time though. Thanks.

Lovely informative article.

Would like to share my blog on north east birding

http://ketkimarthak.blogspot.in/2018/02/flocks-of-birds-neora-valley-lava-jan-18.html?m=1

Ketki

Excellent coverage!

Great pictures & text ,Many many thanks . Jai Hind .